Key findings

1. The UK has seen a significant decline in participation in adult education and training. The number of publicly funded qualifications started by adults has declined by 70% since the early 2000s, dropping from nearly 5.5 million qualifications to 1.5 million by 2020. Although the total number of adults participating in employer-provided training has remained fairly stable over time, the average number of days of workplace training received each year has fallen by 19% per employee in England since 2011.

2. The decline in training participation has occurred alongside a fall in both public and private investment in training. Average employer spending on training has decreased by 27% per trainee since 2011. Since its peak in 2003–04, public funding for adult skills has fallen by 31% in real terms, mostly as a result of a reduction in provision of low-level courses. But the historical decline in funding also reflects long-term freezes in funding rates. Funding provided for an adult learner taking GCSE English or maths has fallen by 20% since 2015–16 in real terms.

3. There are five main policy levers that this (or a future) government might look to in the adult skills policy sphere: the direct public funding of qualifications and skills programmes, loans to learners, training subsidies, taxation of training and the regulation of training. In making changes to any lever, there is a trade-off between the costs of the reform (both the fiscal cost and the cost associated with further policy churn) and the benefits, which depend on whether the reform leads to additional training that is genuinely new and productive.

4. Insuring that public funding of adult education is well spent is key. Adult skills funding is set to increase by 11% on today’s levels, reaching around £4.7 billion by 2024–25. Given the low returns to many adult skills courses, instead of expanding the range of courses that are publicly funded, the government might more helpfully review whether increasing existing funding rates would offer a better return.

5. The student loans system is set to be reformed with the introduction of the Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE), which will merge the two separate loan systems that currently exist for further and higher education. In 2022–23, the amount lent to further education students (£124 million) was less than 1% of the amount lent to higher education students (£19.9 billion). The LLE has the potential to reshape the post-18 student loan landscape. However, progress in implementing the LLE has been slow. And important questions still remain about how the system will be designed, including which courses will be covered by the new loan entitlement. The government should provide clarity on the design of the LLE and ensure that it moves forward with its implementation within a reasonable time frame.

6. The government introduced the apprenticeship levy in 2017 as a means to deliver 3 million apprenticeship starts in England by 2020. This target was not met, with around 2 million apprenticeship starts between 2015 and 2020. While overall numbers of apprenticeships have fallen back, the number of higher-level apprenticeships has almost tripled since 2016, and the average duration of apprenticeships has increased by 22%. Since the apprenticeship levy was introduced in 2017, it has raised £580 million more than has been allocated for spending on skills and training across the UK.

7. The apprenticeship levy should be reformed to have a uniform subsidy rate for all employers. Currently, levy-paying employers (who tend to be bigger) benefit from a higher subsidy rate. While there is a case for subsidy rates being set according to the degree to which training is likely to be underprovided, this would be complicated and difficult to measure and implement in practice, so a uniform rate is desirable. The uniform subsidy rate should also be set at a lower level than the current rates which effectively subsidise the full cost of apprenticeship training.

8. The Labour party has announced plans to broaden the apprenticeship levy into a ‘growth and skills levy’, which will allow employers to use subsidies for non-apprenticeship training. Past experience, with schemes such as Train to Gain in the late 2000s, suggests that there is a risk of significant deadweight costs (i.e. subsidising training that would have taken place anyway). In addition, an extended subsidy would add to costs, which could perhaps be covered by lowering the existing subsidy rates.

9. At present, all spending on employer-provided training is exempt from tax, but the cost of self-funded training only qualifies for tax relief under certain conditions. The government should consider aligning the two systems by providing tax relief for self-funded training on the same basis. This would remove a disincentive for groups such as the self-employed, who are historically less likely to participate in training. Only 13% of the self-employed reported engaging in work-related training in the previous three months, compared with 28% of all employees. However, any tax change would need to be accompanied by careful regulation of training courses to avoid the risk of fraud.

9.1 Introduction

In the UK, nearly 40% of adults now go on to higher education (Bolton, 2023a). Yet university is not the only place of learning beyond the school gates. There is a wide range of education and training undertaken by adults, from vocational courses at local colleges to ongoing on-the-job training and apprenticeships. This post-18 education and training receives less attention than higher education (HE), but is crucial to developing the skills needed by the UK’s workforce and to boosting economic productivity.

Since the early 2000s, participation in adult education and training in the UK has declined. That is true of the fraction of workers who have participated in any training, the average number of hours spent in training, and the intensity of the training that does take place. The decline in training participation – which has not been observed to the same extent in most other European countries – has been associated with declines in both public and private investment in training. Over the past two decades, public spending on classroom-based adult education has shrunk by two-thirds, while surveys of employers show that their training expenditure is also falling.

On the face of it, this decline in UK training provision might seem a cause for concern. Indeed, there are solid economic reasons to suppose that, left to its own devices, the market will deliver lower levels of training than is socially optimal. Borrowing constraints can make it difficult for individuals and employers to invest in training. Uncertainty about the returns to training can make individuals unduly reluctant to invest in potentially useful training. And the full (societal) benefits of training are likely not factored in when individuals and firms make investment decisions. These market failures justify a range of government policies aimed at stimulating investment in education and training.

But a reduction in training provision is not necessarily undesirable from a policy perspective. It could also be that the level of training in the past was suboptimally high – for example, if the government was directly funding or subsidising training with low returns. Or broader shifts could mean that it is now appropriate for there to be less training than in the past. In addition, government policy might simply have been subsidising training that would have taken place anyway (what economists call ‘dead weight’) which could justify cuts to public funding. An assessment of the UK skills policy landscape requires us to look beyond the headline trends and figures.

There is a range of potential policy levers available to a government wishing to address the market failures described above and to encourage employers and individuals to invest in post-18 education and training. In this chapter, we focus on the funding and financing of adult education and training in England. This encompasses four policy areas: the public funding of adult education (which covers funding for post-18 further education), the non-HE student loan system, apprenticeship policy, and the taxation of training. We do not cover other areas in detail, such as the regulation of training, although these are unquestionably important to the skills system.

Over the years, there have been multiple reforms to these different elements of the skills system, often in the wake of major reviews. The result is a policy landscape that is cluttered and too often in a state of flux. This constant ‘chopping and changing’ makes it challenging for individuals and employers alike to navigate the post-18 education system. This is one of the key trade-offs the government must make: although there are certainly aspects of the skills system that could be improved, another round of reforms would add to the policy instability and inconsistency which have plagued the sector.

There is a further, overarching trade-off to be made, common to each of the policy levers available to the government. Policies aimed at stimulating investment in education and training come at a cost. There is a fiscal cost (additional money spent on adult education ultimately means lower spending elsewhere, higher taxes or higher borrowing) as well as the costs of adding to the policy churn in the sector. That must be weighed against the possible benefits. These depend on the extent to which education and training induced by the policy are genuinely new and productive. Would the training have happened anyway, even without the reform? And will it yield economic returns? These are difficult questions to answer, but are crucial to any evaluation of skills policy.

In this chapter, we analyse some of the aspects of this trade-off in the public funding of adult education, the non-HE student loan system, apprenticeship policy and the taxation of training. We begin in Section 9.2 by setting out how adult education and training participation has changed over time and how experience in the UK compares with that in other countries. In Section 9.3, we draw lessons from the history of skills policy. In the following four sections, we then analyse each of the four different policy levers in England through the lens of the trade-off between costs and benefits. The chapter concludes in Section 9.8 by setting out the lessons that can be drawn from this analysis and some of the government’s options for reform.

9.2 Training and skills participation over time

Adult education and training encompass a broad spectrum of education and skill-building undertaken by adults. Due to its wide-ranging nature, defining the scope of training can be complex, and different forms of education and training are captured in different data sources. In this section, we use a range of data sources to set out how participation levels and different types of education and training have changed over time. The central message is that the UK has experienced a decline in adult education and training rates over the last two decades.

Participation in public and employer-provided training

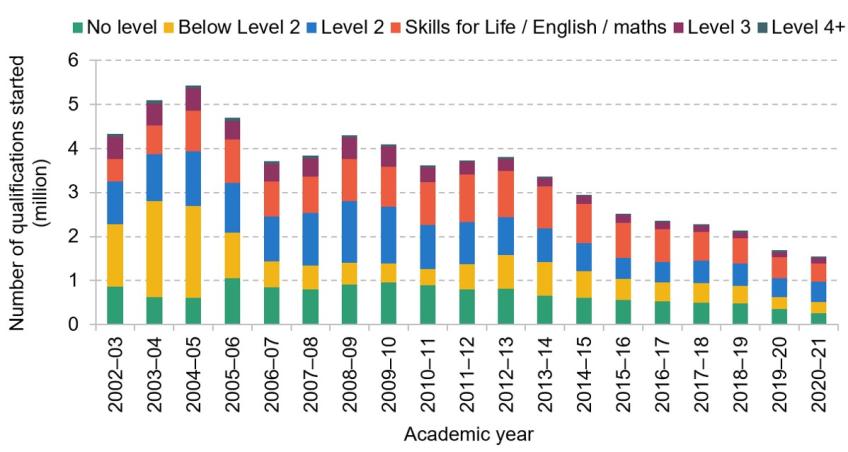

We first examine participation in adult education and training based on its funding source, beginning with publicly funded training. Figure 9.1 shows the number of publicly funded qualifications taken at different levels in England, including both classroom-based qualifications and apprenticeships. In 2004–05, adults enrolled in nearly 5.5 million government-funded qualifications. By 2020–21, that number had dropped to 1.5 million, which marks a 70% decline relative to the peak. There has been a decline in qualifications taken at every level, but there was a particularly dramatic decline in the number of learners studying at the lowest levels (below Level 2) during the 2000s. As we discuss later, much of this decline was driven by deliberate policy decisions aimed at reducing participation in courses that often had low returns to both the individual and society. Therefore, this decline in participation may not be as concerning from an economic and educational perspective as it appears, given the emphasis on directing individuals towards more value-driven courses.

Figure 9.1. Participation in publicly funded qualifications by adults (19+) in England

Note: Level 2 corresponds to GCSE or equivalent. Skills for Life encompasses everyday literacy and numeracy courses. Level 3 corresponds to A-level or equivalent qualifications. Level 4+ corresponds to higher-level qualifications such as Higher National Certificates (HNCs) or Higher National Diplomas (HNDs).

Source: Learner numbers from 2002–03 to 2018–19 from figure 2.2 in Sibieta, Tahir and Waltmann (2021). Learner numbers for 2019–20 and 2020–21 calculated from Department for Education apprenticeship statistics and adult further education participation statistics.

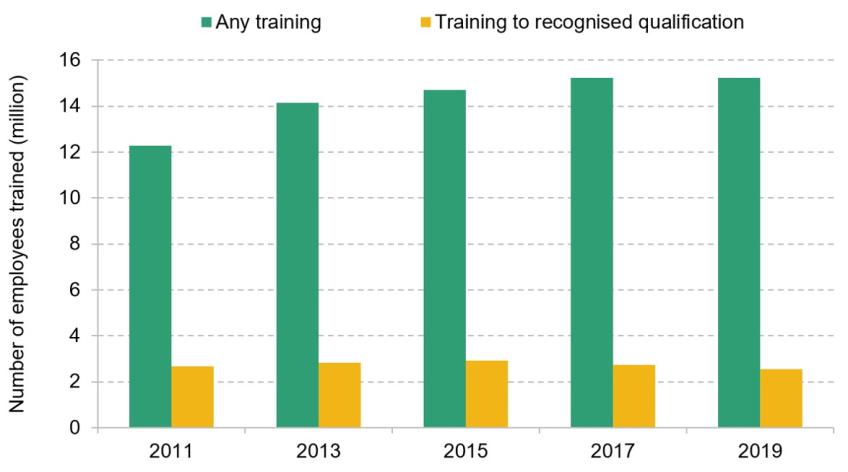

Employer-funded education and training plays a significant role in the development of workforce skills. Data from the Employer Skills Survey (ESS) reveal that overall participation in employer-provided training has largely been on the rise. Figure 9.2 illustrates the number of participants in such training over the past 12 months, spanning the five years of data available on this metric in the ESS. In 2019, over 15 million workers received employer-provided training, which represents a 24% rise since the start of the decade. As a proportion of the overall English workforce, the number of employees in training has remained relatively stable at just over 60% between 2013 and 2019.

Figure 9.2. Participation in employer-provided training over the last 12 months in England

Source: Author’s calculations using data from the Employer Skills Survey.

The nature of employer-provided training can vary greatly, ranging from short courses (e.g. in GDPR compliance) to training towards nationally recognised qualifications. While over 15 million adults participated in employer-provided training in 2019, only 17% (2.5 million adults) trained towards a qualification. Over the 2010s, the number of employees training towards a nationally recognised qualification declined by 5%.

It is also worth noting that a significant proportion of employer-provided training is either health and safety or basic induction training. Of employers who provided training in 2019, 30% reported that at least half of the training they offered fell into these categories and 12% said this was the only training provided to employees (Winterbotham et al., 2020). Hence, a significant share of employer-provided training is aimed at meeting legal mandates rather than directly enhancing workforce skills beyond this.

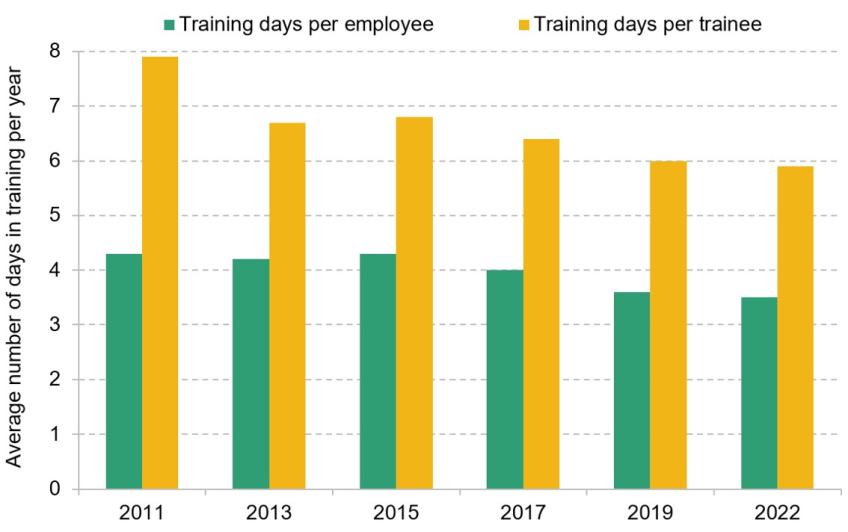

There has also been a reduction in the duration of employer-provided training. In other words, those who are receiving training are receiving it less intensively than in the past. This is illustrated in Figure 9.3, which presents the average number of training days in a year for all employees and for trainees (i.e. employees who received at least some training during the year). The average number of training days has been gradually decreasing since 2011. Between 2011 and 2022, the average number of training days for all employees in England declined by 19%, from 4.3 days to 3.5 days. The average number of training days per trainee fell by a quarter, from 7.9 days per year to 5.9 days per year in 2022.

Figure 9.3. Average number of training days per employee and per trainee in the last 12 months in England

Source: Employer Skills Survey 2022.

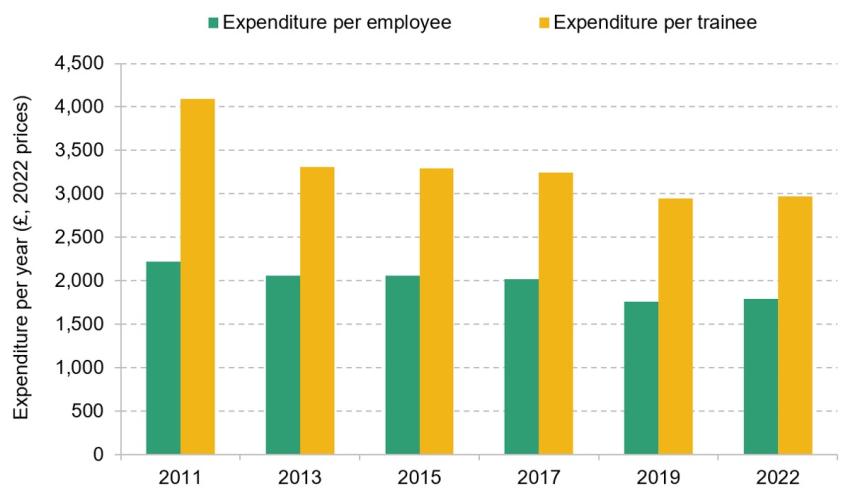

The decline in training intensity is reflected in the training expenditure of employers. Figure 9.4 shows average employer investment in training per employee and per trainee over the last 12 months. Since 2011, average training investment per employee has fallen by 19% (in real terms). The decline in investment per trainee has been more pronounced – there has been a 27% decrease, from just over £4,000 per year in 2011 to less than £3,000 per year by 2022 (both in 2022 prices).

Figure 9.4. Average investment in training per employee and per trainee in the last 12 months in England

Source: Employer Skills Survey 2022.

Taken together, the evidence suggests that although overall participation in employer-provided training has remained fairly constant, there has been a decline in the intensity of training (as indicated by the decline in the share of workers studying towards a recognised qualification, the fall in the average number of days spent in training, and the reduction in average employer investment in training).

The UK in international context

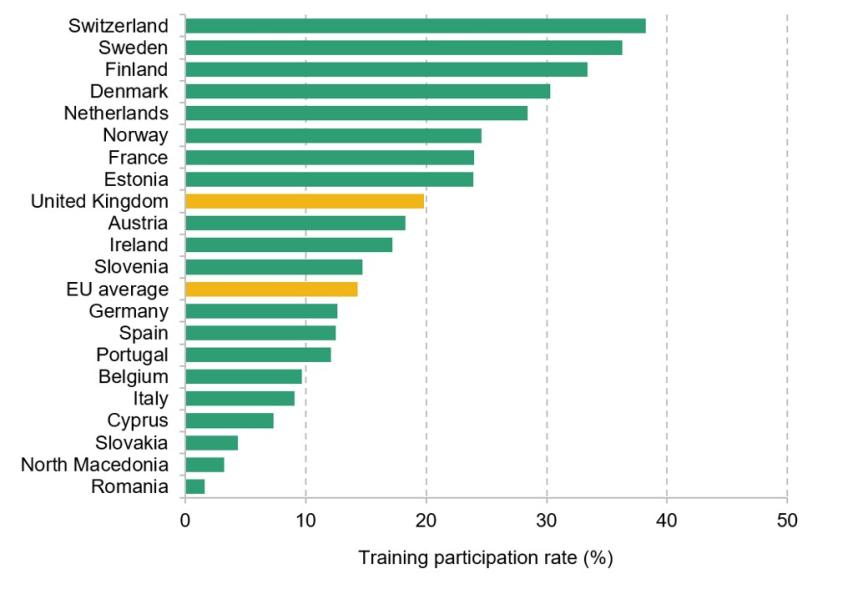

We now turn our attention to how the UK compares with other countries. In general, international comparisons of training rates are difficult, because different countries have distinct education systems and varying definitions of what constitutes training. Any international comparisons must therefore be taken with a pinch of salt. The EU Labour Force Survey provides one measure of training participation across European countries. Figure 9.5 shows employee participation in any form of education and training in the last four weeks. On this measure, the UK fares quite well compared with many other European countries. In 2019, nearly 20% of employees surveyed had participated in education and training in the past four weeks, whereas the average across the European Union hovers just below 15%. The UK’s training participation is, however, well below the rates observed in Switzerland and the Scandinavian countries, which are at the top of this league table.

Figure 9.5. Participation of employees in education and training in the last four weeks, 2019

Note: The figure shows participation by workers aged 25–64 in ‘any education or any training’ over the last four weeks. The EU average shows average training participation among the current 27 European Union member states, i.e. excluding the UK.

Source: EU Labour Force Survey.

Where the UK stands out is the extent to which training participation has declined since 2010. Between 2010 and 2019, the majority of European countries saw an increase in training participation. Across the Europe Union, average training participation increased from 11% to 14% between 2010 and 2019. In the same period, it fell from 25% to 20% in the UK. Hence, the gap between the UK and the EU in terms of training participation has narrowed. Only three countries – North Macedonia, Slovenia and Cyprus – saw a more pronounced decline than the UK over the 2010s.

Although overall training participation still remains relatively high in the UK, evidence from recent studies shows that the UK lags behind on other metrics of training. Li, Valero and Ventura (2020) find that ‘the UK ranks 21st [out of 35 countries] in terms of the share of trainees that receive training that lasts at least 6 days’. Clayton and Evans (2021) show that ‘UK employers invested half as much per employee’ relative to the EU average. This suggests that while a high proportion of UK employers may be offering training, this training tends to be shorter and cheaper than in other European countries. It is worth noting that these conclusions are based on data from 2015. Unfortunately, at the time of writing, the data used in these reports have not been updated so we cannot present a more up-to-date picture on these measures.1

Summary

Participation in training peaked in the early 2000s, since when there has been a decline in both the level and intensity of training. Publicly-funded courses have experienced a marked reduction. Although overall participation in employer-provided training has remained stable (at least over the 2010s), there has been a slight decline in training that leads to qualifications and a fall in time spent in training. Internationally, the training participation rate is currently higher in the UK than in many European countries, but it appears to be on a downward trajectory not seen in most other countries. The gap between the UK and the EU average in terms of training participation has therefore narrowed and, at the latest count, employer investment in training in the UK is lower than in many other European countries.

9.3 The skills policy landscape

There are broadly five areas of skills policy in England, each targeting a different group and addressing a specific type of market failure. Table 9.1 lists these policy areas and provides a brief description. Taken together, these policies form the basis of the government’s strategy to support individuals and employers to invest in education and training. In this section, we trace out how these different areas of skills policy have developed over the last two decades, and also how the intended aims of skills policy have evolved.

Table 9.1. Five areas of skills policy

| Skills Policy | Target | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Direct funding of qualifications and skills programmes | Mainly adults with low existing qualification levels | The government allocates funding for adults (19+) to attain their first qualification at or below Level 3 (A level or equivalent) and access skills programmes. In general, direct public funding is paid to further education (FE) colleges and is designed to help adults with low prior attainment to access education and training. |

| Loans for further education | Adults pursuing further education courses at Levels 3 to 6 (i.e. from A level or equivalent up to degree-level courses) | There are two types of loans available to students in England: higher education student loans and advanced learner loans. The latter are loans to cover tuition fees for further education courses; they are provided on the same terms as HE student loans, but students cannot access maintenance loans. Both types of loans are designed to alleviate borrowing constraints. |

| Apprenticeship subsidies | Available to all employers wanting to hire apprentices | Since 2017, the government has charged a levy on large employers to fund big subsidies for apprenticeship training. This is designed to encourage firms to internalise the wider benefits of apprenticeships. |

| Tax deductibility of training costs | Mainly employers providing training | In the UK, training expenses are tax deductible for employers. This ensures that employers do not face a disincentive to invest in training. |

| Regulation of training and apprenticeships | Education providers | There are numerous rules and regulations governing apprenticeships and other forms of training. These rules aim to ensure a basic level of quality of training, thereby helping individuals and employers make more informed decisions about different forms of training. |

A brief history of skills policy

Since the turn of the millennium, there have been significant changes to the skills policy landscape. We have seen the introduction (and subsequent termination) of various skill programmes, numerous government skills targets, the expansion of apprenticeships and the development of loan funding for learning outside of higher education. A large number of these changes stemmed from skills reviews, such as the Leitch Review, which have also been dotted across the period.

The focus of the government in the early 2000s was improving the basic skills of adults. As part of its Skills for Life strategy, the government set a target of improving ‘the basic skills of 2.25 million adults’ between 2001 and 2010 as measured by the number of adults completing qualifications (Department for Education and Skills, 2007). To implement this strategy, all adults without a Level 2 qualification (equivalent to a GCSE at A*–C) were eligible for free literacy, language and numeracy training. As shown in Figure 9.1, this led to a high level of adult participation in low-level skills courses in the early 2000s. However, there were questions as to whether this broad entitlement was well targeted and led to genuine improvements in the skills of the adult population (Wells, 2007).

Following the Leitch Review in 2006, the government’s skills strategy was still focused on improving the basic skills of adults but through supporting employer-based learning – Train to Gain was championed as the way to promote skills development. Launched in 2006, Train to Gain was a national skills programme designed to support employers to provide workplace training, which included subsidies for employees taking their first full Level 2 qualifications. Yet ultimately the programme was short-lived. A 2009 assessment by the National Audit Office determined that Train to Gain was not delivering value for money. A significant factor in this conclusion was that it did not seem to be generating new training. As a result, just a few years after being heralded as a key pillar in delivering the UK’s future skills needs, Train to Gain was dumped.

The rise of apprenticeships

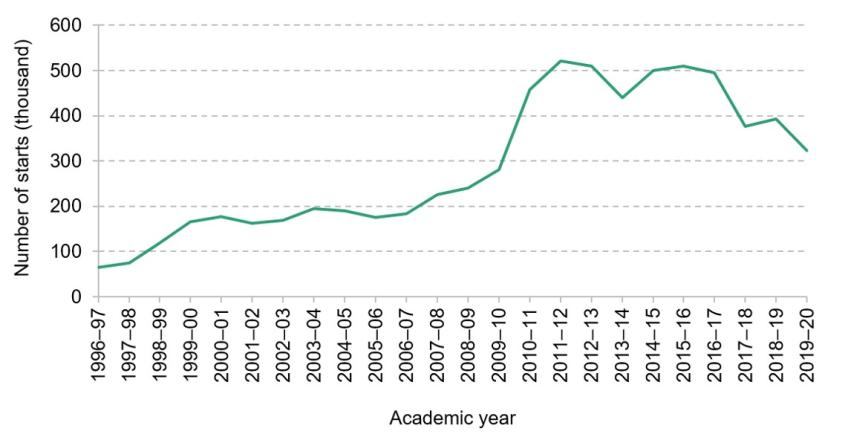

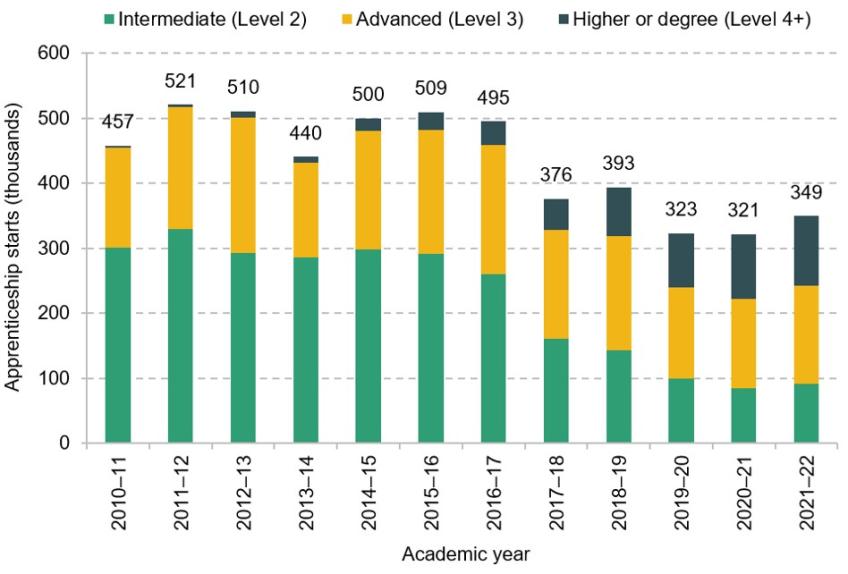

During the 2000s, there was also a pivot towards apprenticeships. In 2004, the government abolished the age restriction that had previously limited apprenticeships to those under 25 (Mirza-Davies, 2015), which led to an increase in older apprentices (Foley, 2021). As Figure 9.6 illustrates, there was a steady rise in the total number of apprenticeships for most of the 2000s, but then a sharp acceleration towards the end of the decade.

Figure 9.6. Number of apprenticeship starts in England

Source: Foley, 2021.

The number of apprenticeship starts in England increased by 63% between 2009–10 and 2010–11, to 457,000. This was almost entirely driven by individuals enrolled in the disbanded Train to Gain programme being migrated onto apprenticeships (Belfield, Farquharson and Sibieta, 2018). There were questions around the quality of these apprenticeships (Wolf, 2011). Many employers simply rebranded existing training programmes as apprenticeships to benefit from subsidies available for this type of training. In some instances, employees were not even aware they had been enrolled in apprenticeships. This underlines the fact that while employer training investment may respond to policy, without appropriate regulation this does not necessarily translate into the type of training that the government intends.

In 2010, the incoming Conservative–Liberal-Democrat coalition government announced a target for 2 million apprentice starts during its parliamentary term. This target was met, with 2.4 million starts between 2010 and 2015. Beyond the government’s headline targets, the early 2010s also saw the start of important regulatory changes aimed at improving the quality of apprenticeships (Mirza-Davies, 2015). The government set out new conditions for training to be classified as an apprenticeship, including a minimum duration of 12 months. The 2012 Richard Review of Apprenticeships set in motion a move from the existing system of apprenticeship frameworks to apprenticeship standards. Frameworks had a greater focus on qualifications, whilst standards, which were introduced in 2017, are more focused on the skills, knowledge and behaviours required in specific occupations.2

The 2015 Conservative government maintained a strong emphasis on boosting apprenticeship numbers. Once more there was a target – 3 million new apprentice starts during the course of the parliament. This time the target was not met, with just over 2 million starts by 2020. During this period, there was also discussion about the need to reform the apprenticeship funding system to finance higher-quality apprenticeships. An influential report by Alison Wolf (2015) proposed a National Apprenticeship Fund where each employer would contribute to funding apprenticeships through a payroll levy. This would not only secure dedicated funding for apprenticeships but also ensure broad-based employer engagement in apprenticeship provision. An apprenticeship levy was subsequently introduced in 2017 and has since been the subject of much debate.

In summary, within a decade, apprenticeships in England fundamentally changed. The number of apprentices grew rapidly, although not enough to meet both of the targets that successive governments set themselves. There was also recognition that the quality of apprenticeship training needed to improve. This led to the funding system being overhauled and to the introduction of new regulations which meant that the apprenticeships being taken at the end of the 2010s looked very different from those taken at the start of the decade. We will analyse the implications of these changes in apprenticeship policy in more detail later in this chapter.

Beyond apprenticeships

While there have been a lot of changes to the apprenticeship system, the rest of the skills system has not escaped unscathed. We do not provide a detailed account of all the reforms that have occurred in the last 20 years here, but we highlight key changes to funding entitlements and the development of loans for adults pursuing further education courses.

Over the years, there have been numerous adult skills programmes targeted at adults with low existing education levels, but many of these skills programmes have been short-lived, largely due to limited evidence of their value for money. Currently, the majority of funding for adult skills is used to provide access to a range of qualifications free of charge to eligible adults. These are summarised in Table 9.2. Generally, funding is provided for an adult’s first full qualification, defined as a substantial qualification typically associated with a clear occupational role. The first four entitlements in the table are statutory entitlements set out in the Apprenticeship, Skills, Children and Learning Act 2009 and are funded through the Adult Education Budget.3

The fifth entitlement is a new entitlement introduced in 2021 and is funded through the National Skills Fund.4

Table 9.2. List of fully funded qualifications currently available to eligible adults

| Entitlement | Example Qualification | Eligibility |

|---|---|---|

| A digital skills qualification, up to and including Level 1 | Award in Essential Digital Skills | Aged 19 and over with digital skills at below Level 1 |

| English and maths, up to and including Level 2 | Functional Skills in English and Maths | Aged 19 and over without a GCSE grade 4 (C) or higher |

| A first full qualification at Level 2 | NVQ Diploma in Mechanical Manufacturing Engineering | Aged 19–23 without an existing Level 2 qualification |

| A first full qualification at Level 3 | Access to Higher Education Diploma in Business Studies | Aged 19–23 without an existing Level 3 qualification |

| A first full qualification at Level 3 for individuals aged 19 and over | Level 3 Diploma in Bricklaying | Aged 19 and over without an existing Level 3 qualification; or currently unemployed / on low income |

Note: A ‘full qualification’ refers to a substantial qualification typically associated with a clear occupational role.

The scope of funding entitlements has generally narrowed over time. Prior to 2012, all adults, regardless of their age, were entitled to full funding for their first full Level 2 or Level 3 qualification. However, from the 2012–13 academic year, the funding entitlement for both Level 2 and Level 3 qualifications was tightened so that people aged 24 and over had to contribute towards the cost of these courses. This led to a decline in enrolments on Level 2 and Level 3 courses (Augar, 2019). As part of the Free Courses for Jobs programme, the government restored the full funding entitlement for Level 3 qualifications in certain subject areas in 2021. However, funding entitlements remain more limited than in the past.

The changes to post-18 education policy have not been limited to lower-level courses. Arguably the most notable post-18 education policy reform in the 2010s was the increase of the higher education tuition fee cap to £9,000. The 2010s also saw the introduction of advanced learner loans (ALLs) in 2013 to support students on further education (FE) courses. Initially, these loans were made available to adults aged 24 and over studying courses at Level 3 or Level 4, but they have subsequently been expanded to all adults (19+) studying FE courses from Level 3 to Level 6. ALLs cover tuition fees for courses – which are mainly taken at FE colleges – on the same terms as HE student loans (i.e. the loans used to fund most undergraduate degrees). But unlike those studying in higher education, further education students cannot access loans for maintenance support.

ALLs represent a tiny fraction of total student borrowing in England. Around 47,000 learners took out ALLs in the 2022–23 academic year with an average loan value of roughly £2,440 per student, accumulating combined borrowing of £124 million in financial year 2022–23. In comparison, nearly £20 billion was lent to around 1.5 million learners in the same period through HE student loans (Bolton, 2023b). Hence, less than 1% of the amount lent to HE students is borrowed through ALLs. From 2025, the post-18 student loan system is set to be reformed. The introduction of the new Lifelong Learning Entitlement will change the student finance that can be accessed by adults taking FE courses – an issue we return to later in this chapter.

Summary

The last two decades have seen a great deal of change in the skills policy landscape, which in part reflects the changing aims of skills policy. There has been a shift from public funding of basic skills courses to employer-based learning, first through Train to Gain and then through apprenticeships. A number of regulatory reforms were introduced in the 2010s to try to ensure that this training meets standards that are more closely aligned with employer needs. There have been new restrictions to accessing publicly funded qualifications, with a shift towards loan-based support. And the post-18 student loan system is due to be further reformed with the introduction of the Lifelong Learning Entitlement.

As a result of this near-constant change, the skills system is often challenging to navigate for learners and employers alike. This means that individuals seeking to further their education or skills may face confusion about the best pathways available, potentially leading to suboptimal choices. For employers, keeping up with the evolving landscape can divert resources and attention from their core training objectives. Additionally, these frequent shifts can undermine trust in the system, making both parties hesitant to fully invest in new opportunities or strategies, for fear that the ground will shift again soon. In essence, while the intent behind the changes may be to better serve learners and employers, the rapid pace of alteration can sometimes have the counterproductive effect of creating instability and uncertainty.

In the remainder of this chapter, we analyse four areas of skills policy in turn: the public funding of adult education, loans for further education, the apprenticeship levy, and the taxation of training.

9.4 Public funding of adult education

A long-standing component of the government’s skills strategy has been direct public funding of adult education and training. This funding falls into two main categories: classroom-based learning and work-based learning. The former is primarily used to fund the skills programmes and funding entitlements outlined in the previous section. In addition, the government provides public funding through advanced learner loans to support adults to access higher-level classroom-based courses. Funding for work-based learning is currently used to subsidise apprenticeship training, although in the past it also supported other employer-provided training programmes, such as Train to Gain.

The decline in public funding for adult skills

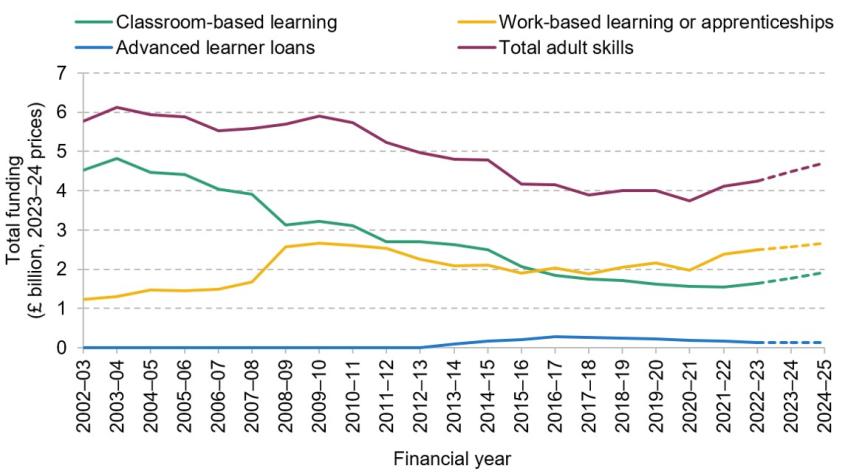

Figure 9.7 shows the level of public funding for adult education and training in England from 2002–03 onwards. We show the overall level of public funding and break this down into three categories: (i) funding for classroom-based learning, which is channelled through a number of different skills funds;6 (ii) funding for work-based learning, which currently consists of the Apprenticeship Budget; and (iii) the amount lent through advanced learner loans.

Figure 9.7. Public funding for adult education and apprenticeships (actual and projected)

Note: The figures for classroom-based learning and work-based learning in 2024–25 are projected spending levels based on spending plans announced in the 2021 Spending Review. For 2023–24, we take the average of the 2022–23 and 2024–25 levels. We assume that the amounts lent through advanced learner loans in 2023–24 and 2024–25 are equal to the 2022–23 level.

Source: See source for figure 6.4 in Drayton et al. (2022). HM Treasury GDP deflators, June 2023.

Total public funding of adult skills has decreased since the 2000s, with current spending at around £4.3 billion – a 31% drop from its £6.1 billion peak in 2003–04 (adjusted for inflation). The trend is most pronounced in classroom-based learning, which, from its peak of £4.8 billion, now receives funding of just £1.6 billion – a decrease of two-thirds over two decades. During the 2000s, part of the decline in classroom-based funding was diverted to work-based learning, so overall spending remained stable. The introduction of Train to Gain pushed expenditure on work-based learning to a peak of £2.7 billion in 2009–10. Since the early 2010s, funding for work-based learning has consistently been around £2 billion in today’s prices, while classroom-based funding has continued to fall. Advanced learner loans were introduced in 2013–14, but they have consistently represented a small share of skills spending.

The government allocated additional future funding to adult education and apprenticeships at the 2021 Spending Review. Based on this additional funding, total public funding for adult skills is set to rise to around £4.7 billion in 2024–25. This is an 11% rise on current funding levels and will take real-terms funding back to levels seen in 2014–15, but still 23% below the peak seen in the early 2000s.

There are two key drivers behind the long-term decline in public funding. The first is a decline in the number of adults taking publicly funded adult education courses. This means that colleges and other education providers receive less funding, as funding is allocated on the basis of the number of courses taken. The decline in participation in classroom-based learning in particular has resulted from the withdrawal of public funding in the 2000s for low-level qualifications, which often had low returns (Belfield, Farquharson and Sibieta, 2018), a large and deliberate shift from classroom-based to apprenticeship training, and the introduction of tighter eligibility criteria for funding entitlements in the 2010s which we documented in the previous section.

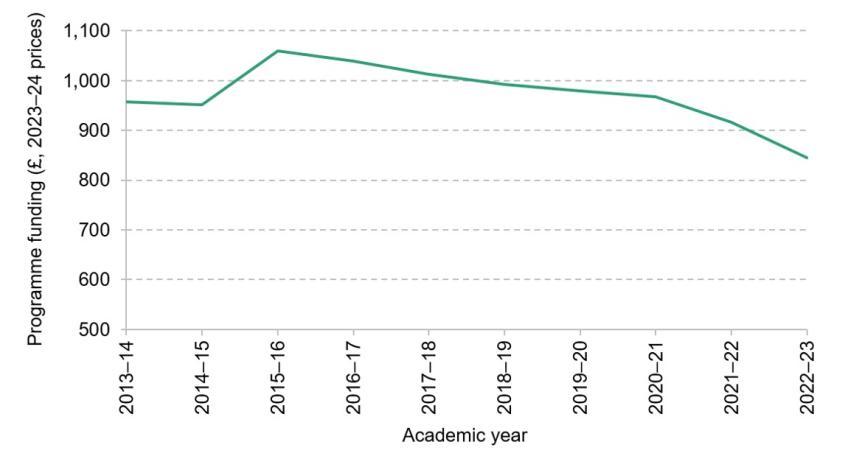

The second driver of the decline in public funding is large real-terms cuts to the funding rates for classroom-based courses, which determine how much education providers receive per course taught. For many courses, the funding rate has not changed in cash terms since 2013 (Sibieta, Tahir and Waltmann, 2021). Figure 9.8 illustrates how programme funding for a GCSE in English or maths has changed in real terms over the past decade. The government increased the funding rate for such a course in 2015–16, but since then providers have received a fixed fee of £811 for teaching this course. This means that, in real terms, education providers are receiving 20% less than they did in 2015–16 for teaching an adult learner a GCSE in English or maths.

Figure 9.8. Programme funding for a GCSE in English or maths

Source: Programme funding rates obtained from Education and Skills Funding Agency’s Adult Education Budget (AEB): funding rates and formula. Inflation rate based on ONS’s CPIH index.

The cash-terms freeze in funding rates is unlikely to represent good policy. Funding rates have been eroded in an unpredictable and arbitrary way, and over time become detached from the resource needs of education providers. Ultimately, this is important because it determines the quality of education received by learners. While there is no direct evidence on the impact of funding cuts on adult learners, there is extensive evidence that school spending levels matter for students’ test scores, completion rates, and continuation into further education (Farquharson, McNally and Tahir, 2022). It is critical that the government reviews whether the existing funding rates accurately reflect the costs of providing adult education courses.

The returns to adult education and training

A key question is whether the government currently sets the right level of public funding for adult skills acquisition. Whether public funding should be used to change participation in adult skills courses depends on the returns to these qualifications. In a recent meta-analysis of studies on the value of FE qualifications in England, Buttar, Alonso and Martin (2023) conclude that FE qualifications tend to (on average) increase earnings. But the earnings boost varies by the type of qualification taken: lower-level classroom-based qualifications typically offer lower returns than higher-level courses and apprenticeships.

Table 9.3 presents estimates of the change in future earnings and employment outcomes (three to five years later) associated with completing different qualifications, along with the number of learners taking each type of qualification in 2020–21 (see the note to the table for a description of each qualification level). It is important to note that these estimates represent findings from a single study, which may not provide robust causal estimates of the returns from completing a qualification, and there are reasons to believe they may be overestimates.7 Moreover, within each qualification, there is a great deal of variation in returns by the subject studied (Buttar, Alonso and Martin, 2023). Nonetheless, the estimates are a useful empirical illustration of the broader conclusions drawn by this literature.

Table 9.3. Wage returns three to five years after completing different levels of adult education, and learner numbers, at Level 3 and below

| Qualification | Increased earnings in employment | Increased change of being in employment | Number of 19+ learners in 2020–21 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Below Level 2 | 2% | 1ppt | 247,830 |

| Level 2 | 1% | 1ppt | 431,860 |

| Full Level 2 | 9% | 3ppt | 24,270 |

| Apprenticeship Level 2 | 12% | 4ppt | 124,080 |

| Level 3 | 3% | 1ppt | 125,450 |

| Full Level 3 | 16% | 4ppt | 52,870 |

| Apprenticeship Level 3 | 13% | 3ppt | 269,660 |

Note: Below Level 2 refers to entry-level qualifications which provide basic knowledge and skills. Level 2 is a GCSE or equivalent qualification. Full Level 2 refers to a substantial course of learning at Level 2, the equivalent of five GCSEs. Apprenticeship Level 2 is the lowest level of apprenticeship. Level 3 is an A-level or equivalent qualification. Full Level 3 refers to a substantial course of learning at Level 3, such as two A-level passes. Apprenticeship Level 3 is also referred to as an advanced apprenticeship.

Source: Update of figure 4.5 from Augar (2019). Learner numbers from Department for Education statistics.

Table 9.3 suggests that there is substantial variation in the returns to different qualifications. The lowest-level qualifications are associated with modest returns: those at below Level 2 result in an average earnings boost of 2%, whereas Level 2 qualifications lead to a 1% increase. In contrast, apprenticeships and ‘full’ level qualifications – which represent a significant course of learning – are associated with higher returns. A Level 3 apprenticeship is associated with a 13% increase in average earnings, and completing a full Level 3 (the equivalent of two A-level passes) is associated with a 16% increase in earnings.

The majority of adult learners were not enrolled in courses with the highest earnings returns in 2020–21, but this is less the case now than in the past: there has been a shift away from lower-level courses over time. In the early 2000s, over 3 million adults were taking qualifications at Level 2 or below each year, but this number has declined to around 700,000 by the 2020–21 academic year. As a proportion of all publicly funded qualifications, the number of qualifications at Level 2 or below has also decreased from around 65% to just under half. In addition, as we discuss later, there has been a significant increase in higher-level apprenticeships in recent years. Given the prioritisation of higher-value courses and training, the overall fall in participation may be less concerning in terms of long-term economic and educational outcomes than initially perceived.

To be clear, low returns do not mean we should remove public funding for lower-level qualifications. The returns presented only reflect the individual monetary returns to these qualifications, and there is evidence to suggest that improving basic skill levels has non-monetary benefits on outcomes such as mental and physical health (Farquharson, McNally and Tahir, 2022). Furthermore, these lower-level courses often act as an important stepping stone to higher-level courses. Yet the results suggest caution when considering further expansions to funding entitlements for lower-level courses or simply reverting back to historical funding levels.

When considering future changes to public funding, the variation in returns to FE qualifications means that any funding needs to be well targeted: it matters how the money is spent, as well as how much is spent. Given the low returns to many classroom-based qualifications, the government should not seek to simply reverse the historical decline in classroom-based learning. Instead, any additional funding might be better targeted at increasing the funding rates paid for courses already in scope, in order to ensure that funding levels accurately reflect resource needs.

9.5 Loans for further education

Financial constraints affect learners at all levels of study, but learners taking more advanced qualifications are typically directed towards loan funding. As we set out in Table 9.1, there are currently two loan systems available to post-18 learners in England: HE student loans and advanced learner loans. ALLs cover tuition fees for FE courses at Levels 3 to 6 (i.e. from A level and equivalent up to degree-level courses) on the same terms as HE student loans; unlike for university students, there are currently no maintenance loans for further education learners.

ALLs represent a tiny fraction of public outlay on student loans: in 2022–23, the amount lent through ALLs (£124 million) was less than 1% of the amount lent through HE loans (£19.9 billion).8 Despite being a small part of the government’s overall outlay on student loans, the financial support available to non-degree learners has been the subject of scrutiny. In September 2020, the then Prime Minister Boris Johnson delivered a speech outlining a Lifetime Skills Guarantee,9 which would support adults to ‘train and retrain – at any stage in their lives’. Central to delivering this aim was the introduction of a ‘flexible lifelong loan entitlement to four years of post-18 education’, giving students at ‘FE colleges access to funding on the same terms as [those attending] universities’.

The reformed loan system – known as the Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE) – is set to be introduced from 2025 and is best thought of as a package of three reforms to the existing post-18 loan system. First, the LLE will unify the two existing post-18 loans systems, with learners studying FE courses being offered maintenance loans like their counterparts studying at university. Second, the LLE will introduce ‘modular funding’, which will allow learners to access loans for specific modules and short courses rather than entire courses. Third, the LLE will remove existing restrictions on accessing loan funding known as ‘equivalent and lower qualification’ rules. Box 9.1 provides further details on the new Lifelong Learning Entitlement.

Box 9.1. The Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE)a

From 2025, the Lifelong Learning Entitlement (formerly the Lifelong Loan Entitlement) is scheduled to replace the two existing systems of publicly funded student loans – higher education student finance and advanced learner loans. The LLE will provide individuals with financial support for four years of post-18 education up to the age of 60, which is the equivalent of £37,000 in current fees. This loan support can be used to finance short courses, modules or full courses at Levels 4 to 6.

The LLE will change the existing system of post-18 student finance in three key ways:

1. Unify funding for FE and HE courses. This will enable people studying FE courses to access maintenance loans, which are currently only available to people studying HE courses.

2. Introduce modular funding, which will enable learners to access student finance to study modules or short courses. Under the existing student loans system, learners access funding for an entire course or a year of study, but the LLE will enable them to access funding for shorter periods of learning.

3. Remove existing restrictions on the study of equivalent and lower qualifications (ELQs), which prevent most students from receiving student finance for a qualification at the same or lower level to one they hold. This could, for example, allow a student to study a Level 6 qualification (e.g. a first degree in history), but then receive loan funding to return to college or university to study a Level 4 qualification (e.g. a Diploma in Electrical Engineering).

Taken together, these reforms will enhance the support available to non-degree learners and should make the existing student loans system more flexible. Yet it is difficult to say just how transformative the LLE will be for adult education. The impact will depend on the extent to which these reforms will stimulate additional demand for education and training, as well as the extent to which this new demand will substitute or complement existing education and training. For instance, the LLE may lead to people substituting long-term courses (e.g. three-year undergraduate degrees) with a series of short courses or modules. The impact of the LLE will also depend on the response of education providers. In order for modular learning to become common, colleges and universities will need to start offering a broader range of short courses which students can then fund through the new LLE.

The government has so far published very little detail on the likely costs and benefits of the LLE. The one exception is an impact assessment by the Department for Education (2023a), which estimates a cost of £6.4 million associated with the ‘regulatory burdens faced by employers and providers in the form of familiarisation costs’. This seems like an incredibly low figure for the costs of such large-scale reforms to the post-18 student loans system. At the time of writing, the Department for Education is preparing a fuller impact assessment which is set to be published later this year. However, it is concerning that potentially such wide-scale reforms to the post-18 funding system are being implemented with such limited evidence on the scale of their likely impact.

We do not assess the impact of the LLE further here, but we note that despite the typical turbulence of the skills system, the implementation of the LLE has been glacial. Since announcing its intention for a ‘flexible lifelong loan entitlement’ in 2020, the government has launched a consultation10 seeking views on its design and scope, and run trials of short courses.11 While involving stakeholders in the design of the LLE is commendable and it is important to test the policy, the process has been very drawn out. More than three years on from the initial announcement, reforms to the post-18 loans system are yet to materialise, and there have been suggestions from within the Department for Education that implementation may even be delayed beyond 2025.12 The prospect of political change further clouds the future of the LLE, creating additional uncertainties for learners and education providers.

In addition, and perhaps more worryingly, there are important details about the LLE that are still unclear. Two of the main areas of uncertainty are which courses will be eligible for the LLE and how credit transfer will work. The government has announced that the LLE will be available for all courses currently funded through HE student finance, but qualifications currently funded through ALLs will only be eligible if there is ‘clear learner demand and employer endorsement’ (Department for Education, 2023b). This a decision that is still being consulted on, but it is critical to the impact of the LLE. On the issue of credit transfer, the LLE could move us into a world where learners study shorter courses potentially at multiple institutions and throughout their lives. To make such a system work in practice, there needs to be a way of recording prior learning and transferring credits from one institution to another. This will require the development of a new credit transfer system, but the government has not yet confirmed how this will work.

In summary, the LLE was announced in 2020 to make the existing post-18 student loans system more flexible and improve loan funding for students accessing further education courses. However, progress on implementing the LLE has been slow and key details about the new system are yet to be confirmed. This is creating uncertainty for the education sector, potentially causing institutions to hesitate in developing or adapting programmes in alignment with the LLE. Such delays can also impact students’ planning and decision-making processes, potentially hindering their educational pathways. Moreover, prolonged ambiguity can undermine the confidence of stakeholders in the proposed reforms. Once the government commits to a reform such as the LLE, it is crucial that it moves forward with its implementation within a reasonable time frame to ensure clarity and timely progress for both learners and providers.

9.6 The apprenticeship levy

As we highlighted in Section 9.3, the last two decades have seen significant changes to apprenticeship policy. These changes have ranged from regulations defining the minimum standards of an apprenticeship, a move towards greater employer involvement in the design of apprenticeships and, in 2017, the introduction of the apprenticeship levy, which overhauled how apprenticeship training is funded. In this section, we examine the apprenticeship levy in detail. We explore how it has changed employers’ incentives to offer apprenticeships, and assess changes in apprenticeship participation since its introduction. Throughout, we analyse different aspects of the design of the apprenticeship levy and options for reform. Box 9.2 summarises key details of the levy.

Box 9.2. Key details of the apprenticeship levy

- Who pays the apprenticeship levy? The levy is paid by all employers (across both private and public sector) who have an annual pay bill of more than £3 million. The ‘pay bill’ is made up of the total earnings (subject to Class 1 secondary National Insurance contributions) of employees, and the levy is paid to HMRC through the Pay As You Earn (PAYE) process.

- How much do employers pay in? Levy-paying employers are required to pay 0.5% of their total annual pay bill above £3 million.

- How are levy funds used? In England, the funds generated through the levy are used to fund subsidies to employers. The subsidies can be used to cover the training and assessment costs of apprentices, but cannot be used to cover other costs, such as wages.

- What are the subsidy rates? The subsidy rates depend on whether the employer is accessing its own levy funds.

- Levy-paying employers can access funding equal to 110% of the amount of the levy paid (i.e. the full costs and a 10% top-up).

- Non-levy-paying employers – and those who have exhausted their fund – receive a subsidy for 95% of the cost of apprenticeship training, and must cover the remaining 5% of costs.

- How did the apprenticeship levy change the subsidy rate? Prior to 2017, the subsidy rates for apprentices were set based on the age of the apprentice:

- 100% of training costs for 16- to 18-year-olds;

- 50% of training costs for 19- to 23-year-olds;

- 40% of training costs for those aged 24 and over (although this rate could vary).

The two dimensions of the levy: taxation and expenditure

The apprenticeship levy is a tax on UK employers that is used to fund skills and training provisions. In England, the majority of the revenue is used to subsidise the cost to employers of providing apprenticeships, while the other UK nations spend the funds raised through the levy on a broader range of skills programmes.

The tax side of the apprenticeship levy

Despite appearances, the apprenticeship levy is not really a hypothecated tax, where the revenue collected goes directly into a separate fund dedicated solely to apprenticeships. Instead, the Treasury sets an Apprenticeship Budget in England at each spending review. While the revenue from the levy is a key factor in setting the Apprenticeship Budget, other considerations such as broader policy objectives can also play a part. The level of allocated funding can be, and has been, different from the amount of money raised through the apprenticeship levy. The devolved governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland receive a corresponding amount via the Barnett formula.

In England, the system has demand-led elements. Levy-paying employers pay into the levy based on their payroll and can access their contributions to fund apprenticeship training. In this context, the funding is responsive to the demands of levy-paying employers: they contribute to the system and decide when and how to use the funds. In contrast, non-levy-paying employers do not contribute directly to the apprenticeship levy but can still subsidise apprenticeships. Their training is primarily financed from the central Apprenticeship Budget, sustained partly by unused funds from levy-paying employers. While the system offers some demand-led components, especially for levy-paying employers, the government retains control mechanisms such as anticipated revenue calculations and caps on funding bands for apprenticeships.

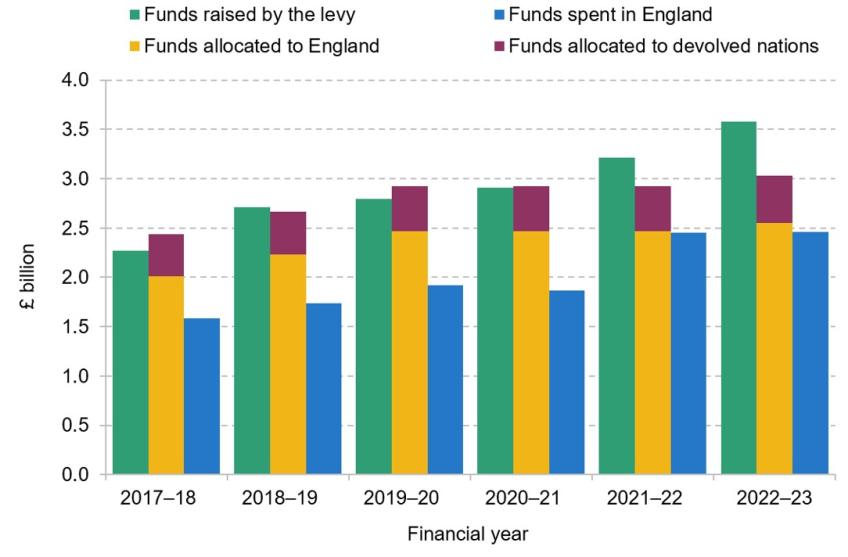

Figure 9.9 shows the revenue generated by the apprenticeship levy, the funds allocated to England’s Apprenticeship Budget and the amounts allocated to the devolved nations, as well as the actual expenditure from England’s Apprenticeship Budget.

Figure 9.9. Funds raised by, allocated and spent from the apprenticeship levy

Source: Funds raised by the levy from the OBR’s Economic and fiscal outlook – supplementary fiscal tables: receipts and other. Funds spent in England and funds allocated to England between 2017–18 and 2021–22 from Mansfield and Hirst (2023). Funds spent in England in 2022–23 from Freedom of Information request, and funds allocated to England in 2022–23 from Department for Education consolidated annual report and accounts 2022 to 2023. Funds allocated to devolved nations between 2017–18 and 2019–20 from HM Treasury and calculated using Barnett formula for remaining years.

The nominal amounts raised by the levy have grown over time, particularly in the last two years, driven by increases in companies’ pay bills due to wage inflation. In the early years of the levy, the amount allocated exceeded the amount raised. However, this has been reversed in the last two years, with almost £290 million more raised than allocated in 2021–22, rising to £550 million in the most recent year. Since the apprenticeship levy was introduced in 2017, it has raised £580 million more than has been allocated across the UK. It is also important to differentiate between the funds allocated in England (through the Apprenticeship Budget) and actual expenditure. The former represents the government’s allocated budget for apprenticeship training, while the latter reflects the real uptake and utilisation by employers. In the first four years of the levy, 75–80% of the Apprenticeship Budget in England was spent each year. The gap has narrowed in recent years, with 96% of the budget being spent in the last financial year.

Given that the apprenticeship levy is not a hypothecated tax, there could be an argument for simplifying the tax system and raising the money through pre-existing taxes rather than having this separate tax. Indeed, the levy already operates essentially as an additional National Insurance contribution (NIC) for large employers, and could therefore be raised by increasing NICs. However, there is international evidence (Marsden and Dickinson, 2013) that having a separate tax labelled as a training levy is advantageous because it makes training investment decisions more salient to employers and also more politically salient.

The expenditure side of the apprenticeship levy

In England, revenue (theoretically hypothecated) from the apprenticeship levy is used to provide subsidies to employers for the cost of training apprentices. The economic rationale for subsidies stems from barriers, such as credit constraints or externalities, which result in fewer apprentices being trained than is socially optimal. There are sound economic grounds to subsidise training, then, and even prior to 2017, subsidies existed for apprenticeship training. The introduction of the apprenticeship levy was associated with two key changes to the existing apprenticeship subsidy system in England – the level of the subsidy and the targeting of differential subsidy levels. The merits of these two changes are debatable.

In 2017, the subsidy rates were significantly increased for adult apprentices (i.e. those over the age of 19). Levy-paying employers (i.e. those with a sufficiently large pay bill to be subject to the levy) can access a subsidy for 110% of training costs. This compares with 95% of the training costs for non-levy-paying firms (with smaller pay bills). These revised rates represent a significant increase on the previous subsidy rates, which covered up to half of apprenticeship training costs for adults. They are also significantly higher than the subsidy rates that are currently set in Scotland13 (up to 50% for apprentices aged over 24) and Northern Ireland14 (50% for apprentices aged 25 and over). The risk of a high subsidy rate is that employers may be less cautious about whether apprenticeships really meet their training needs. In addition, instead of stimulating new training, employers may be induced to relabel existing training as apprenticeships in order to access this subsidy.

To justify substantial public subsidies, one would expect particularly high returns on public investment in apprenticeships in England. Amin-Smith, Cribb and Sibieta (2017) describe how a report published by the government (HM Government, 2015) in the run-up to the introduction of the apprenticeship levy claimed that there was indeed an extremely high return on public investment in apprenticeships – ‘the amount of return is between £26 and £28 for every £1 of government investment in apprenticeships at level 2 and level 3 respectively’. However, these figures greatly overstated the returns to apprenticeships, as the estimates were based on a number of strong assumptions, including very low dead weight and large spillover effects. Although there is evidence that apprenticeships generate positive private returns, as shown in Table 9.3, the returns are not significantly higher than for all other qualifications.

While it could be argued that the government currently fully funds classroom-based qualifications for eligible adults and that apprenticeship training should be treated in the same way, this ignores the differences between the two types of training. Classroom-based qualifications generally provide foundational and ‘general’ skills that are likely be useful across a range of sectors. In contrast, apprenticeships are more likely to foster ‘specific skills’ that meet the needs of a particular employer. As a result, the employer benefits directly from the training and should therefore bear part of the training costs.

Another element of the 2017 reforms was the introduction of a higher subsidy rate for levy-paying firms than for non-levy-paying firms. While it may be tempting to argue that levy-paying firms deserve a higher subsidy rate because they have borne the costs of the tax, this is misguided. The subsidy rate should be set according to the extent to which different employers are doing less training than is socially optimal, rather than according to their historical payments. The existing subsidy system effectively uses employer size (measured via pay bill) as a proxy for this, but this will not reflect the extent of the barriers to providing training faced by different employers. Indeed, there are reasons to believe that smaller firms actually face greater barriers to investment, but they receive a smaller subsidy. For instance, smaller firms are more likely to be credit-constrained (OECD, 2021), which may make it harder for them to internalise the wider benefits of apprenticeships. In practice, it is difficult to measure the extent of market failures, but in the absence of this information, a better approach would be to adopt a uniform subsidy rate for all employers.

The existence of varying subsidy rates also complicates the administration of the current system. A prime example is the levy transfer system, which enables levy-paying employers to transfer their unused levy funds to non-levy-paying employers so that they can benefit from the higher subsidy rate. The rationale for this is that it enables larger levy-paying firms to help firms within their supply chain to improve the skills of their workforce (and benefit from the large firm’s higher subsidy rate), which ultimately benefits both firms. However, this introduces additional layers of administration and requires further decisions – for example, on the allowable amount of the levy transfer. A uniform subsidy rate would remove this additional complexity.

In summary, while there are strong economic reasons for subsidising apprenticeship training, the current system raises several concerns. The prevailing subsidy rates suggest exceptionally high returns to public investment or large market failures in apprenticeship training, but the evidence for these is ambiguous at best. Moreover, the current subsidy rates in England are much higher than those in the other UK nations. The differential rates between levy-paying and non-levy-paying firms also do not appear to reflect the barriers to providing training faced by employers. A move towards a uniform subsidy rate at a lower rate than the existing level for all employers would be more justifiable, more coherent and administratively simpler.

The change in apprenticeship participation

The introduction of the apprenticeship levy, combined with higher subsidy rates, is likely to have increased employers’ incentives to offer apprenticeships. This was particularly the case for older apprentices (those aged over 19), who saw the largest relative reduction in the cost of their training. At the same time though, regulatory reforms in the 2010s, including the introduction of apprenticeship standards in 2017, reduced the ability of employers to offer lower-quality training. This would potentially lead to a reduction in the total number of apprenticeships, and also a change in the type of apprenticeships offered. It is not possible to disentangle the impact of the levy from these regulatory changes, but here we set out how apprenticeship participation has changed in recent years, to provide some insight on the relative impact of these changes.

There are four levels of apprenticeships in England:

- intermediate apprenticeships – equivalent to National Qualifications Framework (NQF) Level 2 (itself equivalent to five A*–C grades at GCSE);

- advanced apprenticeships – equivalent to NQF Level 3 or two A–E grades at A level;

- higher apprenticeships – equivalent to at least a Level 4 qualification (such as an HNC);

- degree-level apprenticeships – equivalent to an undergraduate degree.

Figure 9.10 shows how the number of apprenticeship starts in England at each level has changed over time, with higher and degree-level apprenticeships aggregated together. Between 2011–12 and 2016–17, there were consistently around 500,000 apprenticeship starts each year. The number of apprenticeships then suddenly dropped by a quarter between 2016–17 and 2017–18. This decline coincided with the introduction of the apprenticeship levy but also the transition to apprenticeship standards. Since then, the number of apprenticeship starts has remained below 400,000 in each year. The overall fall in the number of apprenticeship starts has been largely driven by a fall in intermediate apprenticeships. In contrast, the number of higher or degree apprenticeships has almost tripled since 2016–17. In 2021–22, there were 349,000 apprenticeship starts, of which almost 30% were higher apprenticeships, compared with less than 1% a decade earlier.

Figure 9.10. Number of apprenticeship starts in England by level

Source: Number of starts between 2010–11 and 2014–15 from table 2.1 in Further education and skills: March 2020 main tables and number of starts between 2015–16 and 2021–22 from Department for Education statistics.

Beyond the overall decline in the number of apprenticeships and the shift to higher-level apprenticeships, there are several other changes in apprenticeship participation that have emerged. We list some of the key trends below, with corresponding graphs in Appendix 9A.

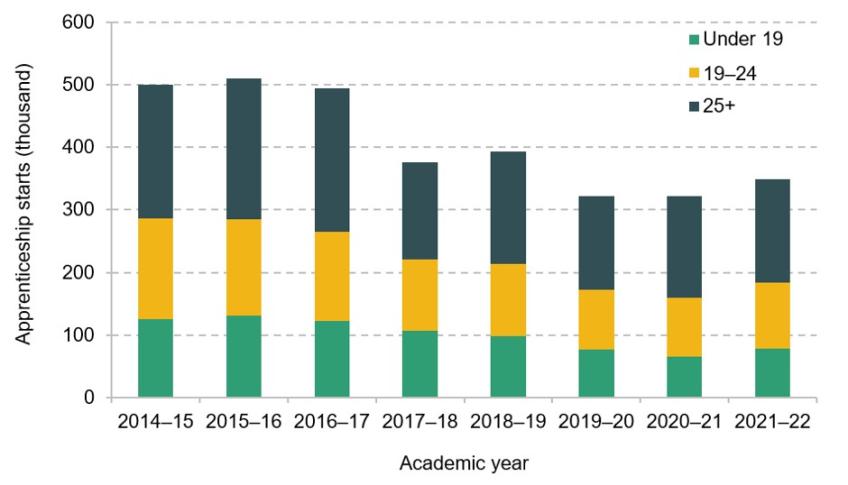

- The number of apprenticeships has fallen across all age groups (Figure 9A.1).

- The number of apprenticeship starts has declined across all age groups since 2016–17. The decline in apprenticeship starts among under-19s has been especially acute – falling by 37% since 2016–17 – yet the number of over-19 apprenticeships has also decreased by 27% over the same period.

- The decline in apprenticeship starts among the older age group comes despite the fact that subsidy rates for older apprentices increased substantially – from 40–50% of training costs up to 110% for levy-paying firms.

- The age limit of 25 for apprentices was removed in 2004, and since then the share of older apprentices has increased. Almost half of people starting apprenticeships in England are over the age of 25.

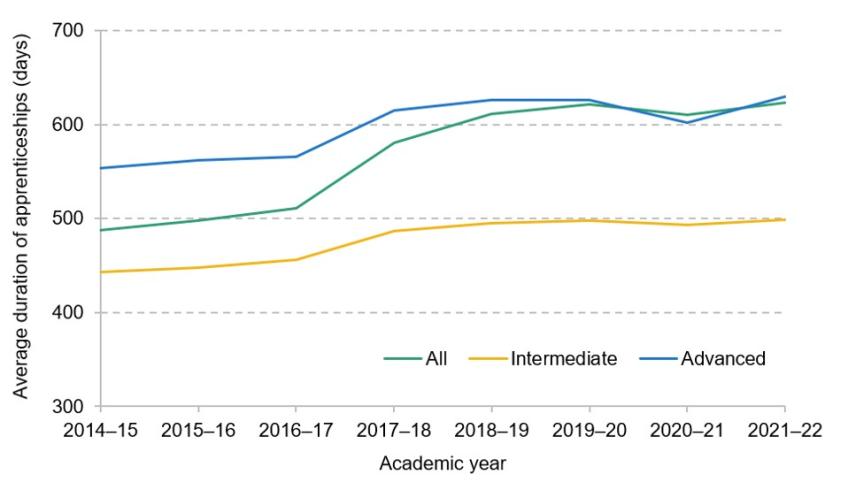

- The average duration of apprenticeships has increased (Figure 9A.2).

- The average length of an apprenticeship increased by 28% between 2014–15 and 2021–22, from 488 days to 623 days.

- There was an especially sharp increase between 2016–17 and 2017–18, with an average apprenticeship started in 2017–18 lasting 70 days more than one started in the previous year.

- This increase was not only due to a change in the composition of apprenticeships, i.e. the increasing share of higher apprenticeships (which tend to be longer). Within each level, the duration of apprenticeships has increased.

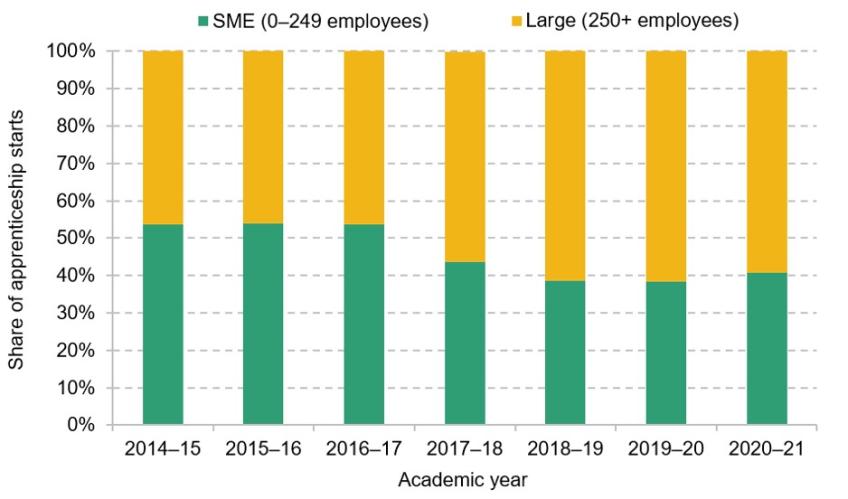

- There has been an increase in the share of apprentice starts at large employers, i.e. those with over 250 employees (Figure 9A.3).

- In the three years preceding the levy’s introduction in 2017, large employers accounted for approximately 46% of all apprenticeship starts.

- In 2017–18, the proportion of apprenticeship starts at large employers increased to 56%. The share grew further to 59% by 2020–21.

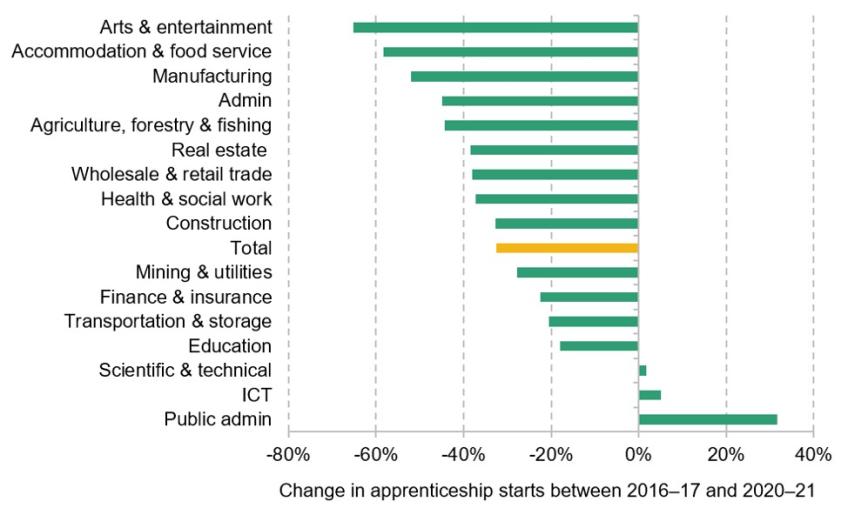

- The number of apprenticeship starts has fallen across most industries with the exception of public administration (Figure 9A.4).

- The sharpest falls in apprenticeships have occurred in industries that previously had a high proportion of intermediate apprentices, such as arts and entertainment, accommodation and food services, and manufacturing.

- Only one sector – public administration – has seen a significant increase in apprenticeship starts since the introduction of the levy. This has been driven by a target for public sector organisations in England to hire apprentices15

Taken together, these trends suggest that regulatory changes had a greater impact on apprenticeship participation than the increase in subsidy rates. Even with increased subsidy rates, especially for older apprentices, there was a fall in apprenticeship starts across all age groups. Additionally, the rise in the average duration of apprenticeships and the shift away from lower-level apprenticeships across all industries suggest that changes to regulations had a significant effect. This underlines the fact that both regulation and fiscal incentives are important for employers who are considering whether to invest in apprenticeship training. Finally, the shift towards higher-level, longer apprenticeships could help improve the ‘brand’ and perceived quality of these qualifications.

Broadening the apprenticeship levy

Since the introduction of the apprenticeship levy, the government has tinkered with its design. For example, the proportion of levy funds that can be transferred to non-levy-paying firms has been raised to 25% (from 10%), and the period over which levy funds can be used by levy-paying firms has been increased from 18 to 24 months (Mansfield and Hirst, 2023). These reforms have sought to maximise the use of levy funds, but they have not changed the scope of the apprenticeship levy: subsidies can only be spent on one specific form of training – apprenticeships.

Employer-provided training can take a number of different forms, and although apprenticeships are now more common than in the early 2000s, it is still only a minority of employers in the UK that train apprentices. The Employer Skills Survey shows that among employers in 2019:

- 11% had staff currently undertaking formal apprenticeships;

- 31% stated that they planned to offer apprenticeships in the future;

- 61% had funded or arranged training for staff in the past 12 months, with 43% funding at least one member of staff to train towards a nationally recognised qualification.

Thus, only a minority of employers currently access funding for apprenticeship subsidies. Furthermore, while we have documented the fall in apprenticeship starts, there has also been a long-term decline in employers providing training towards a nationally recognised qualification – a 5% decline in the 2010s. This raises the question of whether the government can and should do more to improve the incentives for employers to invest in non-apprenticeship training.

One potential reform proposed by the Labour party is to allow firms to spend up to half of their levy contributions on non-apprenticeship training. The reformed ‘growth and skills levy’16 would still require at least half of levy funds to be reserved for apprenticeships, but would provide greater flexibility than the existing system. It would also bring England into line with other countries. Although training levies are common across the world, only two other countries – Denmark and France – have a levy specifically designed to fund apprenticeships (Kuczera and Field, 2018).

Under the existing apprenticeship levy, apprenticeship training is effectively fully subsidised while other forms of training do not receive a subsidy. The near-zero cost of apprenticeship training for employers incentivises them to provide apprenticeships instead of other forms of training. It could be argued that other forms of employer-provided training tend to be more ‘specific’, focusing on skills directly aligned with the employer’s operations. Such specificity, given its direct benefits to the employer, could suggest a reduced need for subsidy. However, there is a vast range of non-apprenticeship training which also develops general skills, and could be more viable to firms than an apprenticeship.

The desirability of broadening the apprenticeship levy also depends on the extent to which this would encourage training that is productive and additional. Compared with other forms of education and training, there is less evidence available on the returns to employer-provided training that is not an apprenticeship. The studies that do exist (e.g. Dearden, Reed and Van Reenen, 2006; Sepúlveda, 2010) tend to show that employer-provided training leads to both higher productivity and higher wages. Méndez and Sepúlveda (2016) show that, on average, an additional spell of employer-provided training in the UK leads to a 0.7% increase in wage rates. However, these studies also highlight the fact that there is a great deal of variation in the returns to different types of employer-provided training, and so it matters which type of training is subsidised.

There is substantive evidence that subsidising employer-provided training leads to a high degree of deadweight loss. Abramovsky et al. (2011) show that the Employer Training Pilot – a precursor to Train to Gain – which provided employees with free training for basic qualifications, did not have a statistically significant impact on the share of eligible employees undertaking qualification-based training. Instead, the subsidy largely substituted existing employer investment. The scrapping of Train to Gain was also, in part, due to a high share of deadweight loss. A National Audit Office report (2009) found that ‘half of employers whose employees received training [under Train to Gain] would have arranged similar training without public subsidy’. Similarly, Leuven and Oosterbeek (2004) show that the deadweight cost associated with an effective training subsidy in the Netherlands was almost 100%. Therefore, broadening the apprenticeship levy may simply pay for training that would have already taken place.

Given the variable returns to training and the large potential for deadweight loss, it is important that there is effective regulation to ensure that the subsidy does not simply pay for mandatory training such as health and safety training. The Labour party has stated that it will create a list of approved courses for the broadened subsidy, but so far no further details have been released. This is a critical decision. The challenge lies in offering employers flexibility to choose the training they need but also ensuring this is genuinely productive and that as much as possible is additional.