The 2017 election saw Labour propose a 45% rate of income tax on incomes above £80,000, and a 50% rate on incomes above around £125,000, with the aim of raising around £4.5 billion per year in revenues. Analysis by IFS researchers at the time concluded that Labour’s revenue estimate was probably little on the high side, but was not implausible. This reflected a high degree of uncertainty about the extent to which taxpayers would respond if their tax rate was increased, and the importance of such responses to the revenue effects of Labour’s proposals.

Today we publish a Briefing Note that presents new analysis of how high income taxpayers respond to changes in income tax rates. The Note is based on three new Working Papers, funded by the Nuffield Foundation, the Economic and Social Research Council and the European Research Council.

The first paper updates and critiques HMRC’s 2012 analysis of responses to and the revenue effects of the UK’s short-lived 50% income tax rate on incomes above £150,000 (which was in place between April 2010 and March 2013). The second uses individual (rather than aggregate-level) data to analyse responses to the 50% tax rate, and looks in more detail at the nature of the responses. It also proposes a new approach for estimating the long-term responses to a tax rate change, when temporary re-timing effects are significant, after finding that existing approaches perform poorly for the 50% tax rate. The third paper looks at how taxpayers respond to income tax thresholds where marginal rates change (such as the higher rate threshold where the rate increases to 40%, and £100,000, where the personal allowance is tapered away, creating a 60% marginal rate).

This observation highlights some key findings of these papers.

Would a 50% rate on incomes above £150,000 raise revenues?

In 2010 the marginal rate of income tax on incomes above £150,000 was increased from 40% to 50%. It was then cut to 45% in 2013, after HMRC had estimated that the 50% rate would probably raise no more than a 45% rate, due to the extent to which they estimate that affected individuals responded to the higher rate by reducing their taxable income. There are a number of debatable assumptions in the methodology used by HMRC to produce those estimates. However, given the range of estimates obtained in our own analysis, we conclude that the HMRC estimate is a reasonable central estimate for policy-costing purposes.

But our analysis also shows that it is plausible that such a policy could raise or cost £1-2 billion a year in revenues. The uncertainty is due to a range of factors, not least efforts by taxpayers to bring forward income to avoid the pre-announced tax rise (termed ‘forestalling’) – this makes it difficult to disentangle these temporary changes in the timing of income from the permanent responses (which is what really matters in the long run for the public finances). In addition, revenue effects depend on the extent to which revenues from other taxes (such as VAT or capital gains tax) and revenues in future periods will be affected by these behavioural responses. Available data do not allow such impacts to be fully estimated.

What about Labour’s recent plans?

Our research finds evidence that the overall high degree of responsiveness of high earners to the former 50% rate was driven by those with the very highest incomes: those with incomes between £150,000 and £200,000 appear to be only a third to a half as responsive to tax rates as the £150,000+ group as a whole.

This implies that Labour’s recent proposals – increasing tax rates above £80,000 – would likely raise additional revenues, although probably not as much as Labour were claiming. Furthermore, the estimates suggest that this additional revenue would likely have come predominantly from those with incomes between £80,000 and £200,000, rather than those with the very highest incomes.

What types of taxpayers and responses drive the overall results?

The new research also provides evidence on the types of response and the income sources driving overall measures of responsiveness to income tax.

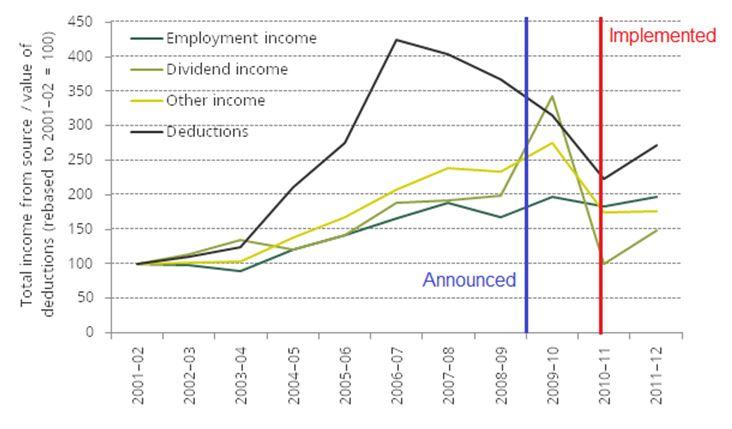

As shown in Figure 1, individuals with dividend incomes, such as owner-managers of incorporated businesses, are more responsive to changes in tax rates than those with employment income. Incomes from this source jumped substantially in 2009–10 (prior to the introduction of the former 50% tax rate), fell substantially in 2010–11 (after the introduction of the 50% tax rate), and remained relatively depressed the following year. In contrast, income from employment was more stable. A similar pattern is found when examining tax thresholds: company owner-manages respond much more to these thresholds than other taxpayers, with virtually no response among employees.

This pattern is likely to reflect the fact that company owner-managers have an additional mechanism through which they can respond to income taxes: they can manipulate the timing of their income by retaining it in or taking it out of their company at a time that lowers their overall tax bills: such as bringing it forward to avoid the 50% tax rate. (This benefit comes on top of the fact that the income they take in dividends gets taxed much less, on average, than the income of employees, as IFS researchers have highlighted).

Figure 1. Trends in different income sources and deductions for groups with incomes greater than £150,000, 2001–02 to 2011–12

Note: The blue vertical line shows when the 50% tax was announced (in March 2009) and the red line when it was implemented (in 2010–11).

Source: Authors’ calculations using SA302 data from 2001–02 to 2011–12.

Evidence from the US typically shows that increases in tax deductions play a major role in taxpayers’ responses to increases in income tax. We find no evidence of this for the UK; Figure 1 shows that the cost of deductions reported on tax returns fell when the 50% tax rate was introduced.

This may reflect restrictions to pension contributions tax relief and associated anti-forestalling rules introduced at around the same time. By reducing allowable deductions, these policies would have tended to push up taxable income, offsetting some of falls in taxable income as people responded to the 50% rate. Analysis of the change in taxable incomes would therefore lead to an underestimate of the extent to which taxpayers reduced their incomes in response to the 50% tax rate. Estimates of responsiveness based on the larger falls in pre-deductions income (which should have been affected by these deduction rule changes) imply a 50% tax rate would likely yield lower revenues than a 45% tax rate on incomes above £150,000.

However, it should be borne in mind that not all deductions relevant for the revenue effects of income tax rate changes are observed in the tax return data we use. First, as already mentioned, income can be retained in companies, so will not be picked up on personal tax returns. Second, contributions to occupational (rather than personal) pensions are deducted from salaries before incomes data is submitted to HMRC. Future work should explore the scale and potential revenue effects of responses via these margins in more detail by linking personal income tax data with corporate tax and occupational pension contributions data.

Concluding thoughts

Taken together the empirical and methodological contributions of these new papers are important. But even with careful analysis, it has not been possible to obtain precise estimates of the responsiveness of high income individuals to income tax rates in the UK.

Part of this reflects the significant forestalling that occurred when the 50% rate was announced over a year in advance. It would be easier to evaluate the longer-term behavioural responses to and revenue effects of future changes in income tax rates if they were announced with (near) immediate effect: affected individuals would not have the time to engage in forestalling activities that hamper identification of the longer-term effects. It would also have the benefit from the government’s perspective of maximising revenues (taxpayers engage in forestalling activities to minimise their tax liabilities). However, tax changes made with (near) immediate effect may be subject to less debate and scrutiny, which may impose its own costs.

Other factors also contribute to the uncertainty: other economic or policy changes can impact on incomes, making isolation of the effects of tax rate changes tricky; and the precise nature of any response, not just its size, will impact on revenues.

Policymakers will therefore need to reconcile themselves to uncertainty about the revenue effects of changing the top rates of income tax. Of course, a central estimate will be required for the official Budget costing. But it is important to be aware of the uncertainty when designing and implementing policy, and be up front about it when ‘selling’ policies to the public.