The government has recently consulted on the structure of alcohol taxes. This consultation focuses on two issues: (i) the introduction of a new still cider and perry band that would increase the tax on products below 7.5% ABV, and (ii) the introduction of a new still wine band that would reduce the tax on products between 5.5% and 8.5% ABV. Here we summarise the main points from our response to selected questions noted in the consultation.

1. Do you agree that there is a case for a new still cider and perry band below 7.5% ABV? and

2. Where do you think the threshold should be set?

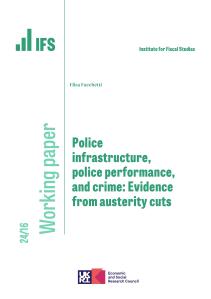

The main rationale for taxing alcohol over and above VAT is that alcohol consumption can generate costs that are not fully taken into account by the drinker. This leads to socially costly overconsumption of alcohol. These costs include the public costs of treating alcohol-related diseases and dealing with alcohol fuelled crime. The aim of taxation should be to raise the price paid by the drinkers who generate these social costs by an amount equal to the (marginal) social cost of drinking an extra drink. The social costs of alcohol consumption are most directly related to the ethanol, or pure alcohol, in drinks. The relevant base for taxing alcoholic drinks is therefore the ethanol content of the drink. The alcoholic strength – the amount of ethanol in a given litre of drink – is known as alcohol-by-volume (% ABV). In Figure 1 we draw the excise duty levied on beer and cider per unit of ethanol for different ABV levels. Currently, beer is taxed per unit of ethanol, with increasing tax rates, meaning that the ethanol in higher strength beer is taxed more heavily than ethanol in lower strength beer. However, EU law mandates that cider is taxed per litre. This leads to stronger ciders attracting a lower rate of tax per unit of ethanol than weaker ciders. Under the current system, cider, particularly high strength cider, is taxed far less than beer. For example, a litre of 7.5% ABV beer attracts £1.38 tax, while a litre of 7.5% ABV cider (which contains exactly the same quantity of ethanol) attracts 40p, or less than a third, tax. This disparity in the tax levied provides incentives for people to choose cider over beer and to consume more alcohol than if cider was taxed the same rate as beer is currently. Similarly, it provides an incentive for companies to sell cider rather than beer in the UK. Introducing a new cider band below 7.5% ABV could change the tax schedule in various ways. There currently are two rates applied to cider products: a lower rate for products below 7.5% ABV and a higher rate to products above 7.5%. We assume that these rates do not change, but a new rate is introduced that lies between the high and the low rate and applies to products with ABV between 7.5% and some lower threshold. even assuming that the rates currently levied would not increase. We consider two alternative specifications of the new band:

- Scenario 1: introduce a rate of 50.71p per litre for products with ABV between 5% and 7.5%. The 50.71p rate is halfway between the current lower rate (levied between 1.2% and 7.5%) of 40.38p and the higher rate (levied between 7.5% and 8.5%) of 61.04p.

- Scenario 2: extend the higher rate of 61.04p to products with more than 2.8%. The 2.8% threshold is the level at which the second band for beer begins. Scenario 2 would be a larger reform, but even this would not do much to address the disparity between beer and cider tax rates for products with more than 4% ABV. Scenario 1 would lead to less change in the cider tax schedule, and would be likely to have only a small impact on the prices, and hence purchases, of high strength cider. Under scenario 1 a litre of 7.5% ABV cider would attract 50p of tax and under scenario 2 it would attract tax of 61p compared to 40p under the current system. In either case this would still be less than half (36-44%) the tax levied on an equivalent strength litre of beer.

Figure 1. Excise duties on beer and cider per unit of ethanol

Notes: Excise duty on beer is levied per unit of ethanol with rates: 8.42p (1.2%-2.8% ABV), 19.08p (2.8%-7.5%), 24.77p (more than 7.5%). Excise duty on cider is levied per litre with rates: 40.38p (1.2%-7.5% ABV), 61.04p (7.5% - 8.5% ABV). Scenario 1 introduces a rate of 50.71p per litre for ABV between 5% and 7.5%; scenario 2 extends the 61.04p rate to products with more than 2.8% ABV. The alternative structure has the following rates per litre: 16p (1.2%-2.5% ABV), 60p (2.5%-4.5%), 90p (4.5%-6.5%), 120p (6.5%-7.5%), 150p (7.5%-8.5%).

There are reasons why it might be sensible to tax one type of alcohol more than another. For example, if heavier drinkers prefer certain alcohol types, then increasing the tax on those products can reduce the most socially costly forms of drinking while limiting the impact of higher prices on moderate drinkers. In recent work, IFS researchers studied the optimal design of alcohol taxes and showed that taxing high strength spirits more than other types of alcohol could reduce the most socially costly forms of drinking. However, they also found that the current tax rates on cider should be brought more in line with those on beer. The EU restriction that cider must be taxed per litre, not per unit of ethanol, makes this more challenging. However, one option would be to introduce more bands and increase the rates on the higher bands, see the alternative structure in Figure 1. If having additional rates – as the government proposes – is feasible under EU law, then the government ought to consider whether having further bands would be possible, see the alternative structure in Figure 1. The UK’s imminent departure from the EU could remove the legal constraint on the base of cider taxation. In this case aligning the cider duty schedule with that for beer would be an improvement on the current system. The government argues cider should be more lightly taxed because it, “is an important part of the rural economy”. As we have discussed above, the rationale for taxing alcohol is to correct for the socially costly effects of drinking. If there are reasons to subsidise the cider industry over the beer, or other industries, then appropriate policy instruments should be designed to do this. However, it is not clear why the cider industry needs government assistance, potentially at the expense of other alcohol – or rural – industries in the UK.

3. In volume terms, how does the still cider market breakdown by strength in 0.1% ABV increments?

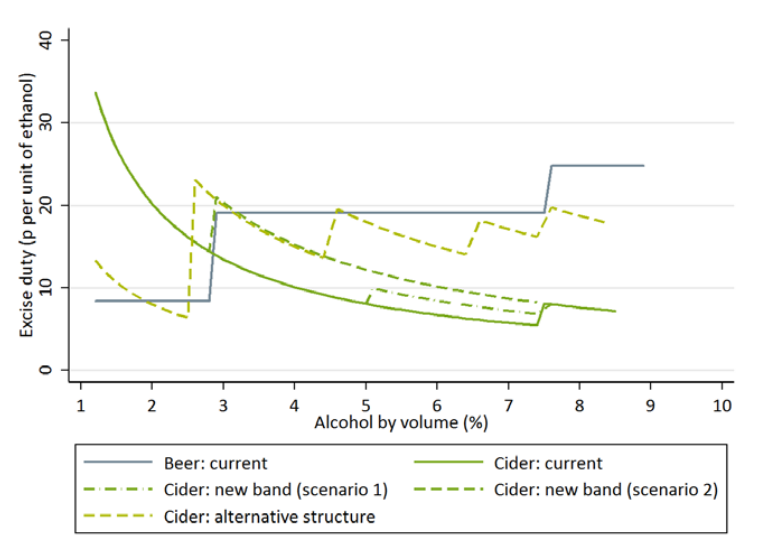

We answer this using data from the Kantar Worldpanel for the off-trade market in 2011. Figure 2 shows the distribution of cider products (left hand panel) and transactions (right hand panel) in the UK off-trade market. There are a group of products with ABV content at the 7.5% threshold (dashed line); these products make up a greater fraction of products available, than purchases. This suggests that if a new band was introduced, then manufacturers might offer new products, or change existing products so that they their ABV content was right at the new threshold. However, this would depend on various factors, including: the costs to manufacturers of changing existing products or introducing new products, and to what degree consumers switched towards them.

Figure 2. Distribution of alcoholic strength of cider products

Notes: Distributions drawn across products (left hand panel) and transactions (right hand panel). Dashed line is at 7.5% ABV. Source: Authors’ calculations using microdata from the Kantar Worldpanel 2011.

4. We would welcome evidence on the impacts a new still cider and perry duty band could have. This includes, but is not limited to, the impacts on: (i) businesses, (ii) consumers, (iii) public health.

The impact of a tax on businesses and consumers, and the resulting effect on public health will depend on a range of factors. Businesses are likely to respond by increasing their prices, but they may do this by more or less than the tax increase, depending on the nature of competition in the market. They may also change prices on products not subject to the tax. Finally, they may respond by changing the alcohol content of their products or by introducing new products. Consumers can respond to these price and product changes by changing what alcohol they buy. The effect on public health will depend, in part, on whether consumers switch to other alcohol products or to not buying alcohol altogether. In the recent work by IFS researchers, heavier drinkers were found to be much more willing to switch between alcohol products in response to price changes, rather than to not buying alcohol at all. For example, following a 1% increase in the price of a cider product, the heaviest drinkers were 10 times more likely to switch to another cider product than the lightest drinkers. This meant that the total alcohol demand of heavier drinkers was significantly less price responsive than lighter drinkers. For example, in response to a 1% increase in the price of all alcohol products, the reduction in the amount of alcohol bought by the heaviest drinkers is only 1/3 the reduction in the amount of alcohol purchased by the lightest drinkers. This illustrates the danger of assuming that the average reduction in alcohol consumption will apply to everyone. Although on average the total amount of alcohol might fall, if the heaviest drinkers are not price responsive, then their alcohol demand will fall by much less. These are likely to be the drinkers whose health would improve the most from a reduction in alcohol consumption, which means the impact of the proposed tax change on public health may be less than is hoped.

Still wine

7. We would welcome evidence on the current and future performance of the lower-strength wine and made-wine markets, including information on volumes sold.

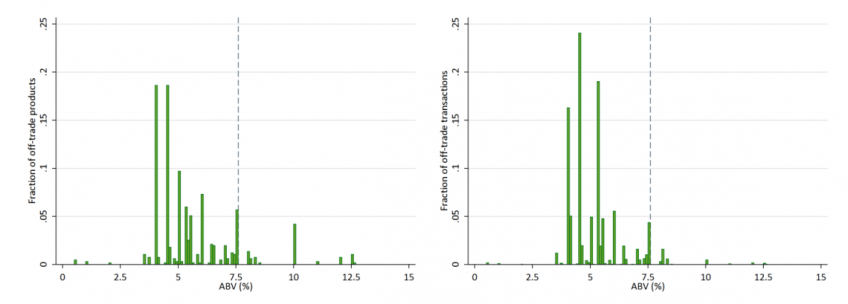

Figure 3 shows the distribution of still wine products (left hand panel) and transactions (right hand panel) in the UK offtrade market. As above, we use data on the off-trade market from the Kantar Worldpanel in 2011. There are fewer than 100 products (out of a total of 4105) available below 8.5% ABV, and purchases of these products constitute only 2% of total transactions in the still wine market. It is possible that lowering the tax on these products would increase the number of products available at this strength. However, it is uncertain to what extent people would switch towards them. This part of the market would have to expand several-fold in order to have a significant impact on overall alcohol consumption. Additionally, if people switch from not buying alcohol at all, to buying wines below 8.5% ABV, total alcohol consumption could even increase.

Figure 3. Distribution of alcoholic strength of wine products

Notes: Distributions drawn across products (left hand panel) and transactions (right hand panel). Dashed lines are at 5.5% and 8.5% ABV. Source: Authors’ calculations using microdata from the Kantar Worldpanel 2011.

Summary

Although the proposed reform to cider duty is small, it is a step in the right direction. However the government should drop its tilting of the playing field in favour of the cider industry, and bring cider rates in line with the tax levied on beer. This would significantly contribute to reducing the most socially costly overconsumption of alcohol in our society. The proposed introduction of a new band applied to low strength wine is unlikely to have much of an effect on total alcohol consumption. Overall this represents a missed opportunity for a more comprehensive review of how alcohol is taxed in the UK.