Recent years have seen increasing concerns in many developed countries over ‘the changing nature of work’. For example, in the United Kingdom, the Taylor Review notes that only 60% of workers are permanent employees. In the United States, a recent review by Mas and Pallais (2020) found that alternative working arrangements such as solo self-employment, zero hours contracts, agency work, independent contractors, and jobs in the gig economy are now more prevalent than ‘traditional’ jobs.

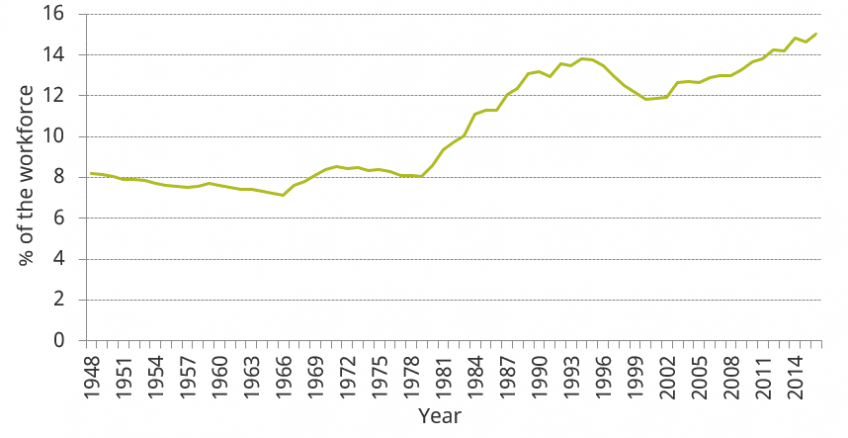

The rising numbers of the self-employed are one of the drivers of these changes. Data from the Bank of England (2018) and the Office for National Statistics (2018a, b) suggest that in recent years the proportion of the UK workforce working for their own business reached its highest level since at least 1854. As shown in Figure 1.1, in the past 20 years the proportion has increased by 3 ppt. With an increasing employment rate and growing population over this period, the numbers of individuals who declare that they are working for their own business as their main economic activity has increased substantially from 3.2 million in 2000 Q2 to 4.8 million in 2018 Q2.

Figure 1.1 also shows that the proportion of the workforce declaring that their main economic activity was working for their own business was broadly flat between 1948 and the end of the 1970s, before growing substantially over the 1980s and again since 2000. Indeed, over the period since 1948, the only significant decrease in the proportion of those working for their own business in the UK workforce was during the recovery from the recession of the early 1990s, due to a sizeable increase in the number of employees during that time.

Figure 1.1. Evolution of the proportion of those declaring that their main economic activity is working for their own business in the total UK workforce

One aspect of concern about the rising number of the self-employed is that the self-employed generally appear less prepared for retirement than employees. In their final report in 2005, the Pensions Commission (2005, p. 278) noted that a ‘disproportionate percentage of the self-employed appeared in danger of inadequate pension income in retirement’. While, for employees, the introduction of automatic enrolment into workplace pensions has stemmed the decline in private pension participation and dramatically increased membership rates, the self-employed are not covered by automatic enrolment. In 2018–19, the Department for Work and Pensions estimates that only 14% of the self-employed participated in a workplace pension, down from 35% in 2003–04. In contrast, in 2018–19, workplace pension coverage among employees stood at 73%. Even among employees not eligible for automatic enrolment, workplace pension membership stood at 32% (i.e. more than twice the rate seen among the self-employed).[1] Furthermore, as we show in this report, historically, employees have often been able to accrue greater state pensions than the self-employed, although since the introduction of the single-tier state pension in 2016, this is no longer the case.

This report analyses state pension provision for the self-employed in the context of these two underlying trends: the rising number of the self-employed and the increasing universality of the UK state pension system. We document trends over time in both the proportion of individuals who, although in paid work, do not accrue a qualifying year towards their state pension and in the value of a qualifying year for working-age adults over time.

The structure of this report is as follows. In Chapter 2, we describe recent labour market trends, and we analyse the characteristics of the self-employed (compared with employees) in 2016, using the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and the Family Resources Survey (FRS). In Chapter 3, we describe how the rules of the state pension system have changed over time. Recognising that the self-employed are unlikely to be self-employed for the whole of their life, we provide both an analysis of how the state pension system works for the self-employed, and how it has changed for other types of workers, such as employees. In Chapter 4, we bring together the material in Chapters 2 and 3 to analyse the trends in coverage of the state pension system. Chapter 5 focuses on the generosity of the system, by looking at the value of a qualifying year and how this has changed over time. Chapter 6 concludes.

Key findings

Those working for their own business are a small but rapidly growing proportion of the UK workforce. In 2016, there were just under 4.8 million individuals working for their own business, and they accounted for approximately 15% of the UK workforce, the highest proportion since at least 1854. A recent rise is explained by both a higher number of self-employed individuals and company owner-managers.

- The self-employed are in a single year less likely than other workers to accrue entitlement towards the state pension. In 2016, 18.6% of self-employed workers did not accrue entitlement towards the state pension because their earnings were too low and they were not in receipt of Working Tax Credit or Child Benefit for a child aged younger than 12. This compares with 14.0% of owner-managers and 5.3% of employees.

- The proportion of workers not accruing state pension entitlement in a given year has increased over time. This increased by 0.9 percentage points (ppt) from 6.2% of workers in 2007 to 7.1% in 2016. Approximately one-third of this increase is due to self-employment becoming more prevalent, one-third is due to a legislation change, which meant an individual needed to have a child aged under 12 rather than aged under16 to qualify for state pension accrual through receipt of Child Benefit, and the remaining one-third through other changes in the prevalence of different types of workers who are able to accrue entitlement.

- The new state pension is typically more generous to the self-employed than the state pension system was previously. The full possible amount of the new ‘single-tier’ state pension is much greater than that available under just the old ‘basic state pension’. In terms of annual accrual, this is slightly offset by the fact that 35 years, rather than 30 years, of National Insurance Contributions are required to receive the full amount and those who manage less than ten years of contributions will no longer receive any state pension.

Self-employed workers who would have accrued entitlement to old state second pension (S2P) could in some years accrue less under the single-tier pension. Self-employed workers receiving Working Tax Credit or Child Benefit for a young child could have received annual accrual towards S2P as well as the basic state pension, which combined was worth more than accrual to the single-tier pension. But, overall, they will still, most likely, end up with a higher state pension under the post-2016 new state pension as most will only have young children for a few years.