Download briefing note | Download press release

"If you’re a woman, you will earn less than a man." - From Theresa May’s first statement as Prime Minister

"Last year Britain was ranked 18th in the world for its gender pay gap ... We can and must do far better." - From Jeremy Corbyn’s campaign speech in July 2016

Gender wage differentials remain substantial and, as evidenced by the quotations above, a hot topic in policy debate. Inequalities between men and women are clearly of direct interest in their own right. In addition, poverty is increasingly a problem of low pay rather than lack of employment. The proportion of people in paid work is at a record high, and female employment has risen especially quickly, particularly among lone parents. Two-thirds of children in poverty now live in a household with someone in paid work.3 In an age when the main challenge with respect to poverty alleviation is to boost incomes for those in work, and when so many more women are in work than in the past, understanding the gender wage gap is all the more important.

This briefing note is the first output in a programme of work seeking to understand the gender wage gap and its relationship to poverty. Section 1 sets out what we mean by the gender wage gap, how it differs according to education level and how it has evolved over time and across generations. Section 2 provides some descriptive evidence on how the gender wage gap relates to the presence of dependent children and the employment outcomes associated with that.

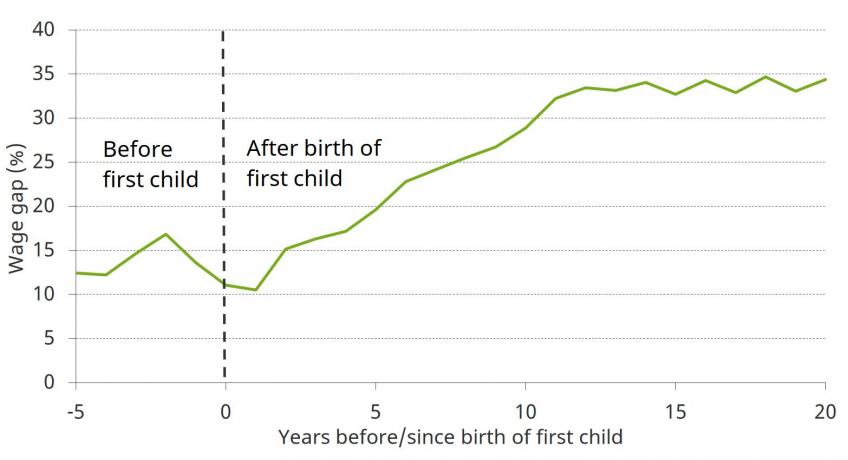

Figure. Gender wage gap by time to/since birth of first child

Key findings:

- Differences in hourly wages between men and women remain substantial, despite some convergence. The hourly wages of female employees are currently about 18% lower than men’s on average, having been 23% lower in 2003 and 28% lower in 1993.

- The gender wage gap has not been falling among graduates or those with A levels. Only among the lowest-educated individuals has the gender wage gap continued to shrink over the past two decades. The other driver of a falling overall gender wage gap has been an increase in the education levels of women relative to men.

- The gender wage gap widens gradually but significantly from the late 20s and early 30s. Men’s wages tend to continue growing rapidly at this point in the life cycle (particularly for the high-educated), while women's wages plateau.

- The arrival of children accounts for this gradual widening of the gender wage gap with age. There is, on average, a gap of over 10% even before the arrival of the first child. But this gap is fairly stable until the child arrives and is small relative to what follows: there is then a gradual but continual rise in the wage gap and, by the time the first child is aged 12, women’s hourly wages are a third below men’s.

- The gradual nature of the increase in the gender wage gap after the arrival of children suggests that it may be related to the accumulation of labour market experience. A big difference in employment rates between men and women opens up upon arrival of the first child and is highly persistent. By the time their first child is aged 20, women have on average been in paid work for four years less than men and have spent nine years less in paid work of more than 20 hours per week.

- Taking time out of paid work is associated with lower wages when returning, except for women who are loweducated. Looking at women who leave paid work, hourly wages for those who subsequently return are, on average, about 2% lower for each year that they have taken out of employment in the interim. This relationship is stronger, at 4% per year, for women with at least A-level qualifications. We do not see such a relationship for the lowest-educated women, which is likely because they have less wage progression to miss out on or fewer skills to depreciate.

- Working low numbers of hours is associated with slower hourly wage growth for women. There is no immediate hourly wage drop on average when women reduce their hours to 20 or fewer per week. But women working no more than that amount see less growth in wages, on average, than other women. Hence, the lower hourly wages observed in lower-hours jobs appear to be the cumulative effect of a lack of wage progression.