Executive summary

Key findings

1. More than 3 million working-age adults in the UK receive health-related benefits. The government has announced plans to first tighten, and then scrap entirely, the Work Capability Assessment – one of the two assessments used for determining eligibility to these benefits.

2. The short-term reform to tighten the Work Capability Assessment will mean some individuals who would previously have been judged as unable to work will lose out on £390 a month and have to carry out work-related activities to keep receiving benefits. This may deliver some savings for the government, although previous reforms of a similar nature have been less effective at doing this than expected.

3. The proposal to scrap the Work Capability Assessment entirely is a more radical change. It would mean moving to a system without a benefit explicitly related to an individual’s capacity for work. The idea is that breaking the link between ability to work and benefit entitlement will encourage individuals with health conditions to move into employment.

4. As a result of this second reform, some working-age people currently receiving health-related benefits because of having limited capability to work would lose them if they are not judged to have a disability that leads to extra costs associated with their daily living. Others who can work and are already receiving health-related benefits because they are judged to have such costs could qualify for additional benefits under the changes.

5. We estimate that, before accounting for any change in behaviour, 320,000 individuals will see their entitlements rise, typically by £390 per month (£1.5 billion a year additional spending), and 520,000 will see them fall by the same amount (£2.4 billion a year less spending). Overall, this would be a £900 million spending cut. For context, official figures suggest that, in real terms, spending on benefits for working-age individuals with health conditions is forecast to rise by £11.9 billion from £61.6 billion in 2023–24 to £73.5 billion in 2027–28.

6. Scrapping the Work Capability Assessment would change people’s financial incentives to work – with 1.8 million seeing their incentives strengthened and 440,000 seeing them weakened. Within Jobcentres, work coaches would need to decide the extent to which individuals should engage in work-related activities as a condition of receiving their benefits. This could help more people into paid work, but it comes with the risk of requirements being inconsistently applied and the potential for hardship if they are applied inappropriately.

7. The reform would base benefit entitlement on the assessment of mobility and ability to do daily living tasks that is used for PIP eligibility – the part of the system that has been growing most quickly for years. This runs the risk of faster growth in spending on health-related benefits in the future.

1. Background

The UK social security system contains two types of benefits aimed at working-age individuals who are disabled or have health-related conditions.

The first of these is incapacity benefits – principally the ‘health element’ of universal credit (UC-health), which is both means-tested and based on an assessment of a person’s incapacity for work.1 In order to be eligible, an individual must be part of a family with low income (the means test) and also judged unable to work or to carry out work-related activity (also known as having limited capability for work or work-related activity – LCWRA)2 . If these criteria are met then the claimant has an extra £390 per month (£4,681 per year) added to their universal credit entitlement. In addition, they are excused from various requirements to be actively seeking work.

The second type of health-related benefits is disability benefits, with the major one for working-age people being personal independence payment (PIP). PIP is non-means-tested and is intended to compensate individuals for higher disability-associated living costs.3 Eligibility for PIP is unrelated to a recipient’s income or ability to work, and depends solely on their assessed inability to do certain tasks (such as dress themselves or get around), which is deemed to generate extra costs. PIP claimants are entitled to between £117 and £749 per month (between £1,399 and £8,983 annually), with the precise amount depending on the severity of their disability.

The differences in criteria mean that it is possible for an individual to be entitled to only incapacity benefits, only disability benefits, or both at the same time. For example, an individual with a spouse who has a high income would be ineligible for incapacity benefits since they are means-tested, even if they had limited capability for work or work-related activity. Alternatively, an individual might have limited capability for work or work-related activity but not incur substantial additional costs in their daily life due to disability, entitling them to incapacity benefits but not disability benefits. As of November 2022, there were 500,000 working-age adults receiving incapacity benefits only, 1.3 million adults receiving disability benefits only, and 1.3 million adults receiving both incapacity and disability benefits (Department for Work and Pensions, 2023b).

There are two upcoming reforms to health-related benefits. The first proposes changes to the assessment used to determine eligibility for incapacity benefits, effectively tightening the criteria. The second is a much more fundamental change to how we support individuals with disabilities or health conditions. We predominantly focus on the latter here, since this would be a permanent and more radical change. But we first offer a few thoughts on the first reform.

2. Tightening the Work Capability Assessment

In September 2023, the government announced a consultation on potential changes to the Work Capability Assessment, the assessment used to decide whether individuals are entitled to incapacity benefits. At a time when the number of claimants and the amount of spending are rising substantially, these reforms would, in short, raise the level of incapacity needed in order to be judged as having limited capability for work or work-related activity. This would be done by changing the assessment relating to mobilising, continence and social engagement; and by restricting or abolishing entirely the ‘substantial risk’ criterion, which grants eligibility in cases where it is judged that not awarding LCWRA would create a substantial risk to mental or physical health.

One of the key reasons given for this change was the rise in numbers working from home, and the opportunity this might provide for people with health conditions to get into paid work. It is not clear, though, that disabled individuals have particularly benefited from this shift, with the increase in the proportion of disabled workers working from home almost identical to the change for non-disabled workers (Murphy, 2023, figure 5). If as a result of this reform, fewer individuals end up being judged as eligible for incapacity benefits, then the government will see some savings. But these will be limited as the changes, at least initially, will only apply to new claims and scheduled reassessments. Moreover, reforms in this spirit have often failed to deliver significant savings (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2019), and this one may apply for just five years. This is because the second reform – to which we turn now – proposes more fundamental changes which will supersede the first.

3. What are the White Paper reforms?

In March 2023 the government published a health and disability White Paper, which set out a number of reforms to health-related benefits (Department for Work and Pensions, 2023a). Some of these are aimed at supporting people with health conditions to get into, and remain in, employment, while others look to improve the experience for individuals applying for and receiving these benefits. The proposals include incentives for businesses to purchase occupational health services as well as increased work coach support within Jobcentres for those in ill health. But arguably the most important reform – and the focus of this report – is the proposed removal of the Work Capability Assessment (WCA), the assessment used to judge whether applicants to UC-health are fit to work, and its replacement with the PIP assessment.

This would be a radical change. It implies moving to a system with only cost-related benefits, one of which is means-tested and one which is not – and no benefits that are explicitly conditioned on inability to work. The objective of this change is to encourage individuals with health conditions to move towards work, by removing the link between benefit eligibility and ability to work. The reform is due to be applied to new benefit claims from 2026–27, with existing claimants being reassessed no earlier than 2029.

In the remainder of this report, we explore the potential effects of this change, considering who might win and lose, and how different groups’ incentives would be affected.

4. Who are the winners and losers?

We begin by identifying the number of individuals who might gain or lose from the plan to remove the WCA, assuming no change in behaviour in response to the reform (we explore the effect on incentives in the next section). The available data here are somewhat limited, and so these estimates – derived from administrative data from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and survey data – should be seen as broadly illustrative.4 Our methodological approach is outlined in the appendix.

The main potential beneficiaries from the reform are those who are receiving PIP, claiming universal credit, but not currently receiving the health element of UC. These are people who receive cost-related benefits but do not receive incapacity-related benefits, so a change making both benefits cost-related leads to them automatically receiving UC-health as well as PIP.5 We estimate that around 320,000 people are in this category and their additional entitlements could cost up to £1.5 billion per year.

The main potential losers from the reform are those currently receiving the health element of universal credit, meaning they are judged as having limited capability to work, but not receiving PIP. This may be because they are judged to have a disability that impedes their ability to work but does not create additional costs day to day, or it may be because the individual has not made a claim for PIP despite being eligible. Since they do not receive cost-related benefits, they would not be eligible for any health-related benefits under the White Paper reforms. As a result, they would no longer receive UC-health (£390 per month). This would be the case for approximately 520,000 individuals, saving the government up to £2.4 billion per year. Some of these 520,000 individuals would continue to receive UC-health despite not qualifying for PIP.

For a large number of individuals, the reform would have no immediate effect in terms of their benefit income. This is true for all those already receiving both PIP and the health element of universal credit. Since they already receive cost-related benefits, they would keep both benefits following the reform, the only difference being that now their eligibility for UC-health is due to their PIP assessment rather than to the WCA. These individuals number roughly 1.3 million. There are also around 900,000 individuals who receive PIP but do not claim UC, and the reform has no immediate effect on these people either.

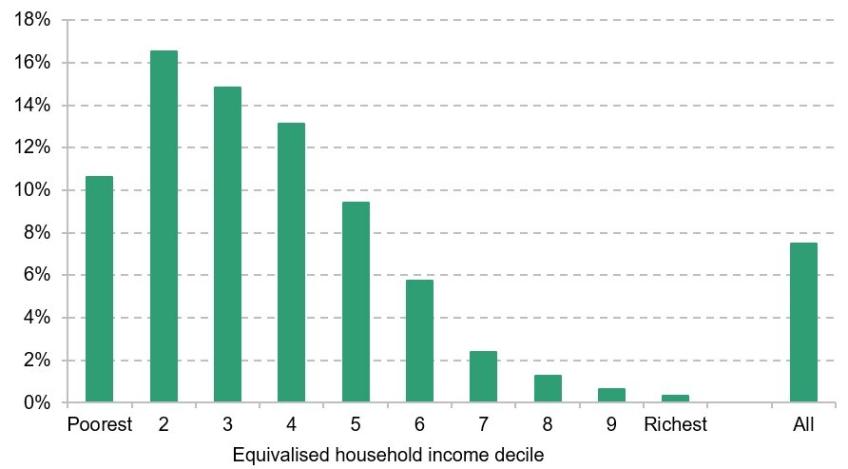

We now briefly examine the incomes of those affected. Figure 1 shows the fraction of working-age families across the income distribution that receive a health benefit (incapacity or disability) and a means-tested benefit – broadly, the type of families that are affected by this reform.6 Generally, affected families are in the bottom half of the income distribution. Families higher up the income distribution are much less likely to be affected due to both being in better health and not satisfying the means test – indeed, these two things are related: Banks, Karjalainen and Waters (2023) show that disability rates are much higher for those with low levels of education (and thus, on average, income). The average affected family has a net household income of £29,200 per year, and 19% have an income of under £15,000.7 (These figures exaggerate the extent to which receipt occurs further up the income distribution, since when placing households in income deciles there is no adjustment made to account for the additional living costs associated with disability – the costs that PIP is explicitly designed to address.) At £390 per month (£4,681 per year), UC-health therefore represents a substantial fraction of income for many of those set to be affected by the reform.

Figure 1. Share of families receiving a means-tested benefit and a health benefit, by household income decile

Note: Working-age families in England and Wales.

Source: Authors’ calculations using Family Resources Survey, 2016–17. We use the 2016–17 data because they largely precede ESA being replaced with the health element of universal credit. We cannot observe which individuals receive the latter, only the number receiving universal credit in general.

5. What are the effects on incentives?

So far, we have explored the effects on individuals’ benefits entitlements, before any potential changes in behaviour induced by the reform. The key idea of the policy, though, is to remove financial barriers to work for individuals receiving UC-health, by breaking the link between benefit entitlement and capacity to work. Under the current system, it is possible for an individual to work while receiving UC-health, but under quite limiting conditions. If a claimant is receiving UC-health, then DWP can require them to undertake another Work Capability Assessment – and potentially lose UC-health eligibility – if their weekly earnings rise above £166.72 per week (equivalent to 16 hours at the National Living Wage).8 Someone earning more than that amount who is not already receiving UC-health, and not eligible for PIP, cannot become eligible unless their earnings fall below the threshold.

Following the scrapping of the WCA, individuals would no longer be reassessed and risk losing their UC-health element if they find a job that takes them over the earnings limit. They would continue to get the top-up to their universal credit so long as they remain in receipt of PIP. This would be an additional increase in spending from the policy, which is not captured in the estimates presented in the previous section. In the following analysis, we document the changes in work incentives induced by the reform, assuming that before the reform an individual earning more than £166.72 cannot be entitled to UC-health, whereas post-reform earnings have no implications for UC-health entitlement. Effectively, this means assuming any individual who undergoes a WCA because their earnings exceed the threshold is not judged as having a limited capability for work or work-related activity.

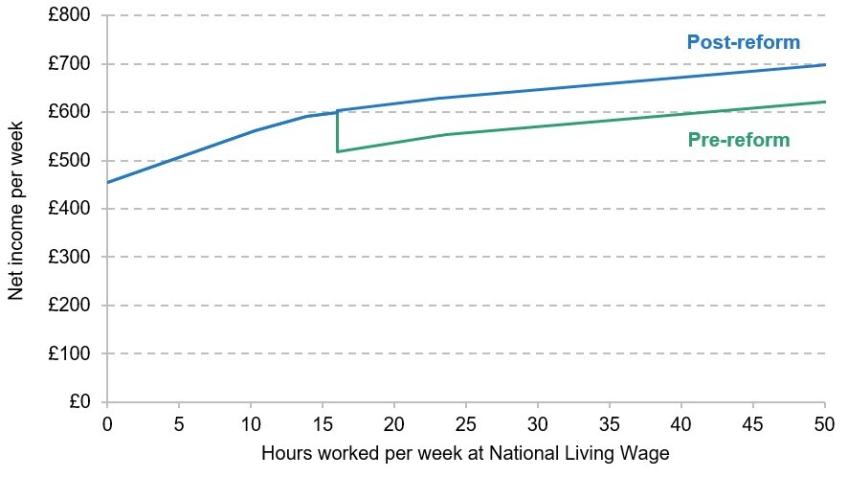

For those individuals currently receiving both UC-health and PIP, the White Paper reform would strengthen their financial incentive to work. Figure 2 shows this effect for an example individual, on the National Living Wage, satisfying these criteria. Their income when working up to 16 hours per week is unchanged by the policy: when below this level, the individual receives UC-health and PIP both pre- and post-reform. Their income when working more than 16 hours is higher after the reform, since working more than 16 hours no longer necessitates another WCA which could lead to them losing their entitlement. Under the existing regime, working 40 hours per week might not result in much higher income than working 16 hours due to the potential loss of UC-health. Under the reform, this would not occur and so any work would increase net income.

Figure 2. Weekly income for example lone parent with two children earning the National Living Wage, entitled to PIP and UC-health before the reform

Note: Net income from all sources after tax, National Insurance and other deductions. Assumes individual is a homeowner, with both children under 5, and is entitled to standard daily living and mobility components of PIP. Assumes that, pre-reform, individual loses UC-health eligibility when working more than 16 hours.

Source: Authors’ calculations using TAXBEN, the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model.

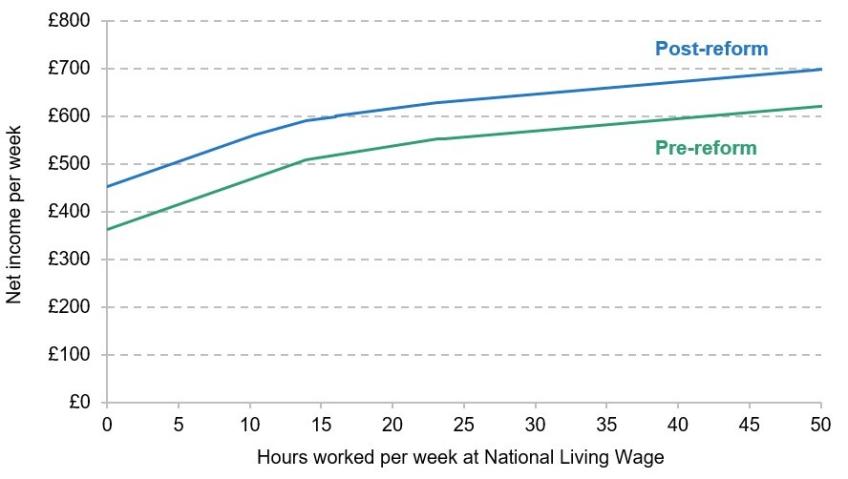

There are groups for whom the White Paper reform would weaken work incentives, however. One such group is individuals on PIP with sufficiently low income to qualify for universal credit who are not receiving UC-health. They satisfy the means-test and cost-related requirements, but might not have been judged as having a limited capability for work-related activity. Or they may simply have not applied for UC-health despite being eligible. Before the reform, they do not get UC-health – but after the reform they would. This raises their replacement rate – the ratio of net income out of work to net income in work. This is shown graphically in Figure 3, which shows that the reform simply shifts up their income at all hours of work (including zero) – meaning that their out-of-work income has become larger relative to their in-work income. This is an ‘income effect’ which tends to reduce the amount an individual is willing to work.9

Figure 3. Weekly income for example lone parent with two children earning the National Living Wage, entitled to PIP but not UC-health before the reform

Note: Net income from all sources after tax, National Insurance and other deductions. Assumes individual is a homeowner, with both children under 5, and is entitled to standard daily living and mobility components of PIP.

Source: Authors’ calculations using TAXBEN, the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model.

These two examples highlight how the proposed changes can influence work incentives in opposite directions. Overall, we estimate the removal of the WCA will strengthen the work incentives of 1.8 million individuals and weaken them for around 440,000. Of course, many of these individuals will not enter or exit work in response to the reform. Some individuals’ health conditions are so severe that they are not able to work, no matter how strongly incentivised (more than one-third of PIP recipients receive the highest possible award), and for others the costs to work will greatly outweigh the returns. Still, we do have substantial evidence internationally that disability benefit recipients are responsive to changes in financial incentives to work (Autor and Duggan, 2003; Maestas, Mullen and Strand, 2013), and so the changes in these financial incentives are likely to induce a response for some.

As well as changing work incentives, the reform would also strengthen the incentive for individuals to start claiming PIP – because now getting PIP also grants entitlement to the health element of universal credit. The extent to which PIP claims might rise should not be underestimated – of UC-health recipients not receiving PIP in February 2019, 29% started receiving PIP by November 2022 (Department for Work and Pensions, 2023b). This suggests that there may be a substantial pool of UC recipients, not on PIP, who could make a successful application – and many will be more likely to do so if they are otherwise left on a lower income and there is much more money at stake.

6. Implementation risks and challenges

So far, we have focused on how the White Paper reforms affect individuals’ benefit income and their financial incentives. There are also a number of risks and challenges associated with the implementation of the reforms, which we touch upon in this section.

By using the outcome of the PIP assessment to determine eligibility to UC-health, the government would reduce the number of assessments that must be carried out. This would reduce the burden on people who claim both benefits, and it would deliver an administrative saving to the government. But it would also increase the fiscal risk associated with the outcomes of PIP assessments. For a long time, disability benefit cases (including PIP) have risen even faster than incapacity cases (including UC-health), meaning this reform could lead to the number of UC-health cases growing more quickly. This could potentially lead to much greater spending on health-related benefits (for more details on spending risks, see Emmerson, Mikloš and Stockton (2023)).

Another risk of this reform comes from the (low-income) UC-health claimants who do not qualify for PIP, for whom losing out on UC-health would represent a big drop in their income. The government may come under pressure to avoid this, and potential ways to do so would be to expand PIP eligibility to include these individuals or to carve out exceptions to allow specific groups to access UC-health without receiving PIP. In its consultation, the government already announced that it would make exceptions for claimants receiving UC-health due to pregnancy risk or because they are receiving cancer treatment. This will mean that in the new system, eligibility for UC-health will not entirely depend on an individual receiving PIP, and it will raise the question of whether this exemption should be extended to further categories of claimants. While expanding PIP would ensure that the individuals of concern do not see a big drop in their income, it would expand eligibility to an entirely new set of people who were not previously getting UC-health or PIP. It is difficult to see a way in which the government could, in the long run, protect the group of individuals set to lose out from this reform without growing the system further. Changing rules or adding large numbers of exceptions would also limit the gains from simplification.

Finally, scrapping the WCA would substantially increase the demands on work coaches in Jobcentres, as the reform would need them to set specific work requirements that determine how much work or work-related activity benefit recipients must engage in to avoid being sanctioned. This would be made particularly difficult by the absence of any assessment of recipients’ capability for work, previously offered by the WCA, and the fact that work coaches are not medically trained. Unsuitable work requirements could result in individuals losing out on benefit income because they cannot carry out the activities asked of them – or disabled individuals engaging in activities that are inappropriate for their condition. That said, if work coaches are able to set personalised requirements well, this could make it easier for benefit recipients in ill health to move back towards work in a manner that reflects their condition. Getting this aspect of the reform right will be absolutely vital in determining its effectiveness.

7. Conclusion

In this report, we have explored the potential impacts of upcoming reforms to health-related benefits in the UK. The first change, which will tighten eligibility for incapacity benefits (UC-health), will likely mean fewer recipients than in the absence of reform, but the effect will be limited because the change will initially only apply to new claims and scheduled reassessments. The effects of the more fundamental reform – the scrapping of the WCA, which is scheduled to take place at the end of the decade – will be more substantial. We find that, in the absence of any other changes, more than 800,000 individuals in England and Wales would see either an increase or decrease in their benefit incomes. We also estimate that the incentive to work will be strengthened for around 1.8 million individuals while it will be weakened for around 440,000. It is more difficult to judge how these incentive changes would translate to actual changes in working behaviour. Part of this is likely to hinge on how well the system is applied by work coaches, who will be given increased responsibility in setting work requirements.

The reform could generate savings for the government and would reduce the burden on applicants by reducing the number of assessments required, since applicants for health-related benefits would only need to undergo one assessment rather than two. The reform could produce further savings if it induces greater employment. But there are also risks on the other side. First, it would likely lead to a greater number of PIP applications. Second, expanding benefit entitlements based on the PIP assessment could lead to much greater spending, as disability benefit cases have historically risen faster than incapacity benefit claims. Third, it would be difficult to protect those claimants set to see their benefit income fall without further expanding the system to include another group of individuals who previously received no health benefits at all.

Methodological appendix

Calculating who benefits and loses from the WCA reforms requires information on what combination of UC-health, PIP and other means-tested benefits individuals are getting. Administrative data on this are not regularly available, and survey data imperfectly record disability and (especially) incapacity benefit receipt. We combine information from an ad hoc data publication by the Department for Work and Pensions (2023b) with survey data to estimate these figures. A rough outline of our method is as follows:

- We use data from the ad hoc DWP publication to give us the number of individuals in England and Wales (as of November 2022) receiving different combinations of UC-health and PIP. For example, this gives us the number of individuals receiving UC-health but not PIP (520,000).

- The DWP publication also contains information on whether individuals on PIP receive other means-tested benefits such as universal credit. This is necessary for calculating who among PIP recipients would be eligible for the means-tested universal credit health element. How an individual’s income and work incentives are affected by the reform depends upon the exact combination of benefits they receive.

- We use TAXBEN, the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model, and the Family Resources Survey 2021–22 to simulate the number of people currently in work and on PIP who would be eligible for universal credit if they were out of work (and therefore have their work incentives affected by the reform). This is necessary since we only observe them in work, so we rely on TAXBEN to produce a counterfactual.

Data

Department for Work and Pensions, NatCen Social Research. (2021). Family Resources Survey. [data series]. 4th Release. UK Data Service. SN: 200017, DOI: http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-Series-200017.