In an initial response to the Scottish Government’s budget for next year, David Phillips, an Associate Director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said:

“Income tax has again ridden to the rescue for the Scottish Budget, generating an additional £700 million in funding for the 2024–25 budget than was expected this time last year. This isn’t really about the income tax rises announced in the Budget – which only raise £82 million, equivalent to less than 36 hours of Scottish NHS spending – but because of improved underlying revenue performance. The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) has substantially revised up its forecasts for income tax revenues in each of the next five years, following better-than-expected revenues since 2021, and forecasts for earnings growth in the coming years that substantially exceed the OBR’s. If it turns out that earnings in Scotland do grow faster than in the rest of the UK, that will genuinely be a sizeable boon to the Scottish budget. But if instead either the OBR is being too pessimistic about UK-wide revenues or the SFC too optimistic about Scottish revenues, as is perhaps more likely, this boost to revenues would not materialise.

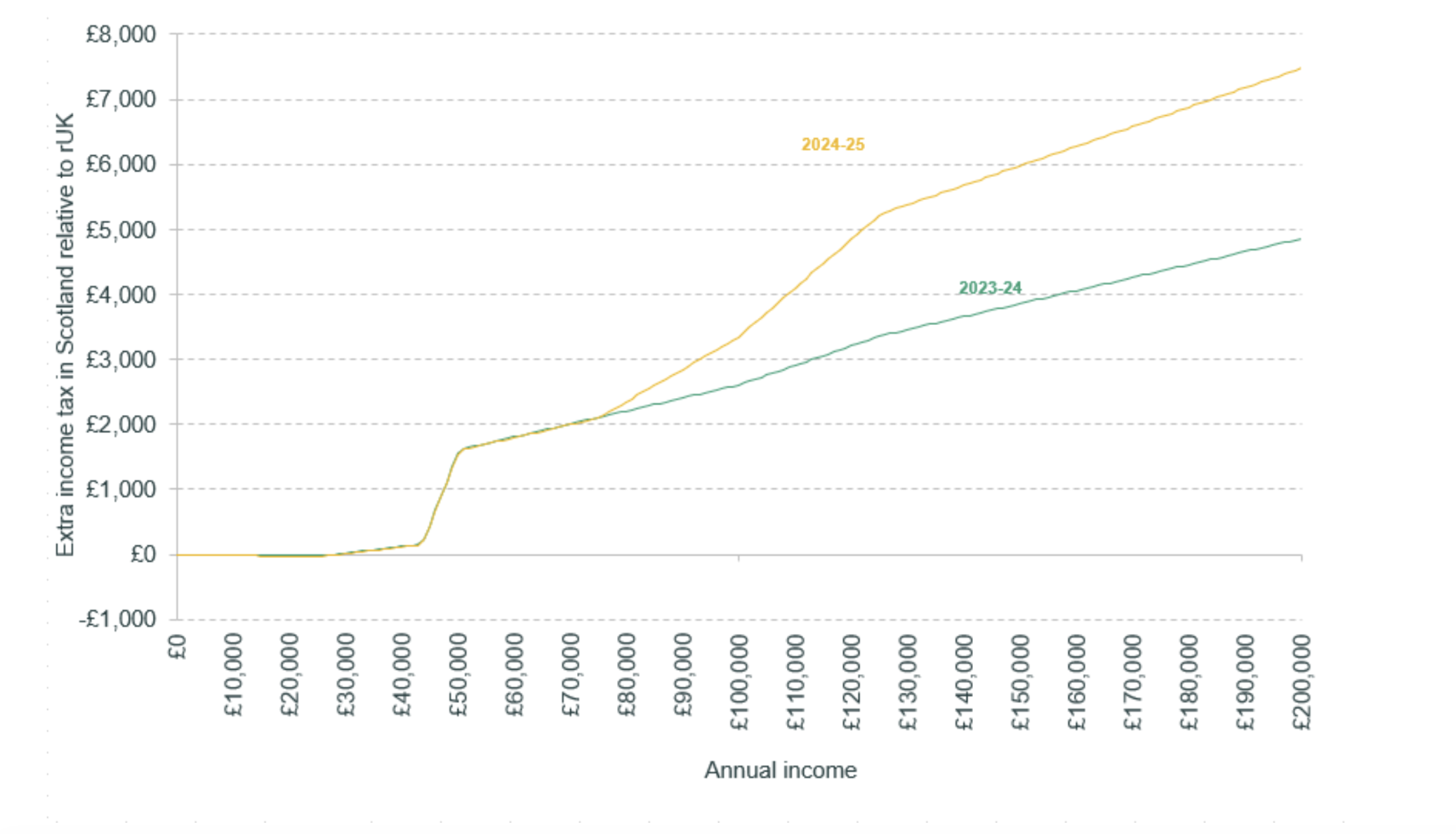

“While small beer in the context of the budget, the income tax increases announced in the Budget are more sizeable for those affected by them. For example, a Scottish taxpayer with an income of £125,000 will pay £5,221 more in income tax than they would in rUK – equivalent to a 7% hit to their post-tax income. In addition, the SFC estimates that behavioural responses offset 90% of the increase in the top rate of tax from 47p to 48p in the pound. At some stage, the Scottish Government will have to look beyond income tax (for example, to council tax) if it wants to continue raising revenue from richer Scots.

“On the spending side of the budget, rather than publish medium-term spending plans as expected, the Scottish Government chose to publish plans for next year only. The Scottish Government’s figures, which compare spending plans with initial budgets for the current financial year, show a real-terms increase in funding for devolved public services of 2.2%. However the SFC’s figures, which compare spending plans with the latest forecast position for this year, imply a real-terms cut in funding for devolved public services of 0.4%.

“In contrast to the Welsh Budget, also published today, where the NHS was prioritised to the exclusion of almost every other area of spending, the Scottish Budget provides the Health and Social Care budgets with smaller increases than most other departments. Compared with the initial budget for 2023–24, funding for Health and Social Care is set to grow by just 1.3% in real terms (although the amount for front-line services is up a bit more), compared with 2.6% for the Education and Skills portfolio and fully 9.1% for the Justice portfolio. This is a strikingly different prioritisation – and it would not be unexpected if, as in the last two years, funding had to be reallocated to the NHS during the course of the year.”

Introduction

In contrast to its previously stated plans, the Scottish Government today chose to publish a single-year budget for 2024–25 rather than updated medium-term spending plans (which it instead plans to publish next May). However, the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) has published projections for the Scottish Government’s funding for the period to 2024–25, which allows us to look at the medium-term picture as well.

Funding for day-to-day (resource) spending is set to be substantially higher next year than was expected a year ago. To some extent, this reflects a higher block grant adjustment for and spending on devolved social security benefits – largely reflecting higher-than-expected inflation (which leads to bigger increases in benefit rates). But even stripping this benefits expenditure out of the picture, funding for day-to-day public service spending is set to be £1.7 billion higher in 2024–25 than was assumed in December 2022. What explains this?

Income tax revenue performance

In part it reflects additional funding from the UK government – including £320 million from the recent Autumn Statement, largely as a result of decisions to extend business rates relief for the retail, hospitality and leisure sectors in England. But in a continuation of recent trends, much more important has been a big upwards revision in the expected contribution of devolved income tax revenues to the Scottish budget. In the coming year, the SFC now expects devolved income tax revenues to make a net contribution to the 2024–25 budget of £1.4 billion, up from the £0.7 billion it forecast last December.

In response to questioning following the delivery of the Budget, the Scottish Deputy First Minister and Finance Minister suggested that this was a result of the policy decisions being taken. But the increases in income tax announced (which we discuss further below) only contribute about a tenth of this improvement in the income tax position. Much more important is the fact that underlying revenue forecasts have been revised up substantially following better-than-expected out-turn figures for 2021–22 and a good showing in provisional data for 2022–23 and the current financial year. Two factors underlie this: first is that earnings appear to have grown a little faster in Scotland than in the rest of the UK (rUK) over this period; and second is the fact that Scotland’s lower higher-rate threshold (£43,662 versus £50,270 in rUK) and higher taxes on high earners mean ‘fiscal drag’ is boosting revenues even more than down south.

The SFC forecasts a further improvement in the net income tax position in 2025–26 and beyond, both because its own forecasts for earnings growth exceed the OBR’s and because of continuing additional ‘fiscal drag’. However, what matters most for the contribution of income tax to the Scottish budget is not the absolute growth in Scottish earnings, it is how that growth compares with growth in earnings in rUK. If it is simply the case that the SFC is more optimistic about earnings growth in general rather than in Scotland in particular, at least some of the forecast boost to Scottish Government funding from income tax revenues may not materialise.

Scottish Government funding

These higher forecast income tax revenues, alongside extra UK government funding, and a number of other factors, mean that compared with original Budget plans for 2023–24, funding for day-to-day (resource) spending is set to increase next year by just under 6% in cash terms, equivalent to around 4% in real terms. A significant part of this relates to further increases in spending on Scotland’s devolved social security benefits – partly due to inflation and partly due to the roll-out of Scotland’s more generous benefits. Stripping this out, the amount available for day-to-day spending on public services is set to increase by 2.2% in real terms, compared with original budgets for the current year. These are the comparisons the Scottish Government likes to focus on.

However, the SFC also publishes updated figures for the current financial year. If we instead compare the budget for next year with the latest position for the current year, funding for day-to-day public service spending is set to fall by 0.4% rather than increasing by 2.2%.

Moreover, despite a bigger cash-terms budget for 2024–25 than expected this time last year, funding for public services is set to be a little lower in real terms than expected a year ago. This reflects the fact that inflation turned out to be higher than expected in 2022–23 (6.7% versus 4.9%) and is expected to be much higher in the current financial year than previously forecast (6.1% versus 3.2%). This higher inflation means next year’s cash-terms funding will stretch less far than it otherwise would.

Spending areas

Comparing planned spending in 2024–25 with initial budgets for 2023–24, how is spending set to change for different services?

Different areas are set to see very different changes. Spending on Justice is set to be 9.1% higher in real terms than initially budgeted for in 2023–24, and funding for the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (up 10.3%) and the Scottish Parliament budget (up 6.1%) are also set to increase substantially (although these are very small parts of overall funding).

In stark contrast to Wales, which also published its Budget today, spending on the NHS Recovery, Health and Social Care budget is set to grow by just 1.3% according to Scottish Budget figures (although the amount for front-line services is up by a bit more): less than the average for all public services. And 2024–25 is set to see real-terms falls in day-to-day funding for the Wellbeing Economy, Fair Work and Energy portfolio (down 8.8%) and the Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands portfolio (down 4.2%).

It is important to note that if we were instead to compare planned spending next year with the latest positions for the current year (our preferred approach), these figures may differ somewhat. We will return to this issue tomorrow once we have had a little more time to crunch the numbers.

Scottish devolved taxes

As highlighted above, the Finance Minister announced a number of changes to income tax. The thresholds for the 19% and 20% rates are both to be increased by inflation, reducing tax liabilities by at most £10.17 per year. In addition, from next April, the top rate of tax (on incomes above £125,140) will increase from 47% to 48%, and a new 45% band of income tax will be introduced on incomes between £75,000 and £125,140. These latter two changes represent a tax increase on the highest-income 5% (154,000) of Scottish income tax payers. The Scottish Fiscal Commission estimates that this change will raise £82 million, after accounting for behavioural responses such as migration, working less and more tax avoidance, which it estimates will reduce the yield by 59%.

These changes will further increase the gap in tax rates faced by higher earners in Scotland relative to the rest of the UK, as illustrated in Figure 1. A taxpayer on £125,000 will pay £5,221 more in Scotland in 2024–25 (up from £3,356 in 2023–24) – equivalent to about 7% of their after-tax income. Someone with an income of £50,000 would pay £1,542 more tax in Scotland. Those with incomes below around £29,000 per year will pay slightly less tax in Scotland than they would in the rest of the UK (by up to £23 per year).

Figure 1. Differences in income tax between Scotland and the rest of the UK

Note: Assumes all income is from non-savings, non-dividend sources.

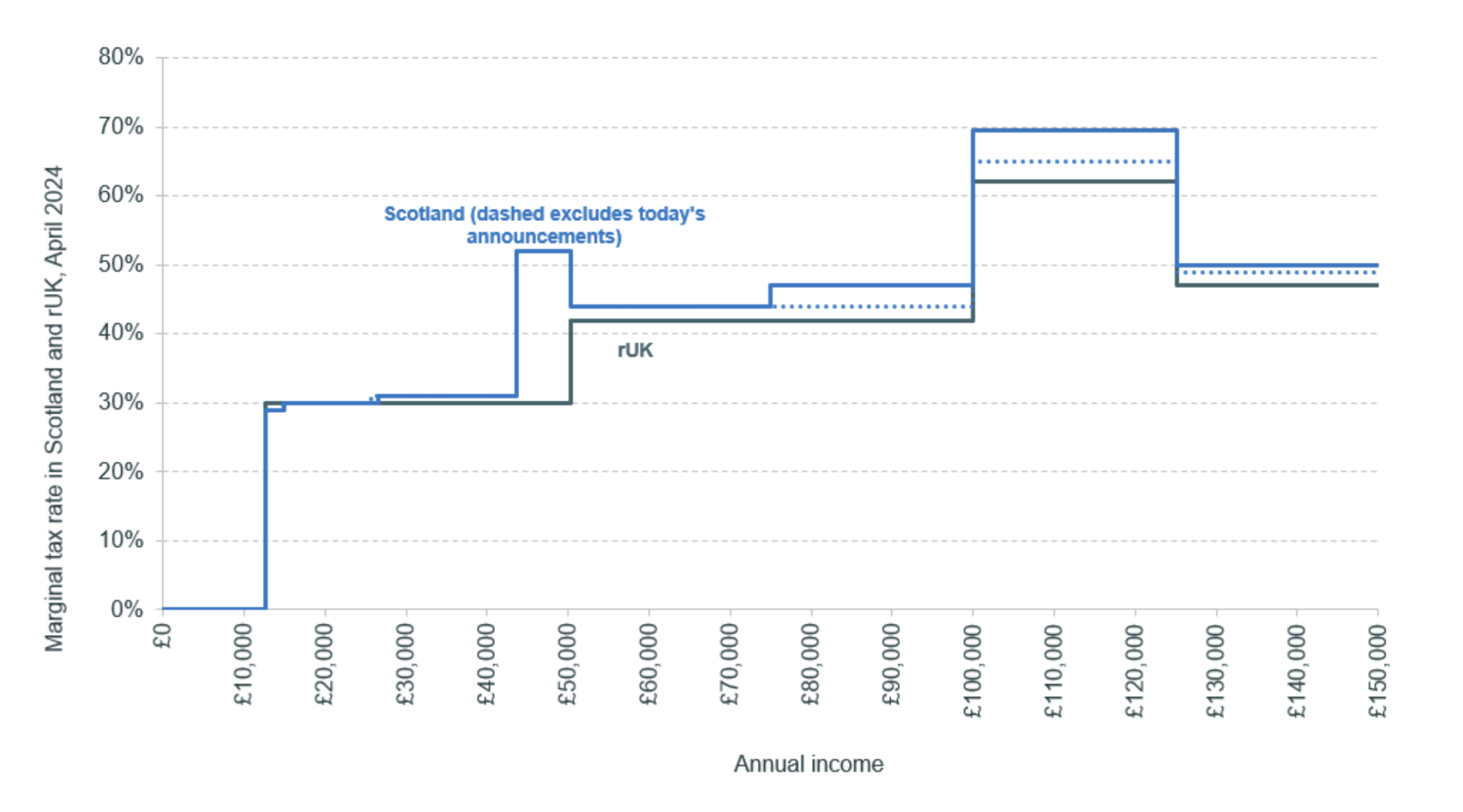

Because of National Insurance contributions and the withdrawal of the income tax personal allowance, the total marginal tax rate (additional tax paid from an extra pound earned) for those earning between £100,000 and £125,140 will be 69.5% from April (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Differences in marginal tax rates between Scotland and the rest of the UK (2024–25)

Note: Assumes all income is from non-savings, non-dividend sources, and includes employee National Insurance contributions.

Apart from income tax, the Scottish Government confirmed a freeze in council tax. Alongside this it has made £144 million of the funding it makes available to councils conditional upon them agreeing to freeze council tax: approximately the equivalent of what they could raise from a 5% increase. This means it is spending over 1.5 times as much on the council tax freeze as is being raised from the increases in income tax on higher-earning Scots.

In addition, the Scottish Government mirrored the UK government’s policy of freezing business rates for small properties, while increasing them in line with inflation for medium and larger properties. As in the current year, it chose not to replicate the UK government’s special reliefs for the retail, hospitality and leisure sectors on the mainland. But it did choose to introduce a 100% relief for hospitality properties on the Scottish islands (capped at £110,000 per business). In the short term, this will reduce the costs and support the viability of the businesses benefiting from the policy, but if this policy is extended (as has been the case several times with policies operating more widely in England), the biggest beneficiaries are likely to be landlords as rents increase.