Earlier in the year we launched the Pensions Review, a multi-year project aimed at finding ways to improve the future of financial security in retirement. As part of the Review, abrdn Financial Fairness Trust, working with the Institute for Fiscal Studies, commissioned new polling from YouGov of over 3,000 working-age people to examine people’s concerns about the pension system, and investigate their understanding of it. In this short piece, we highlight some of the main findings of this exercise.

Confusion reigns

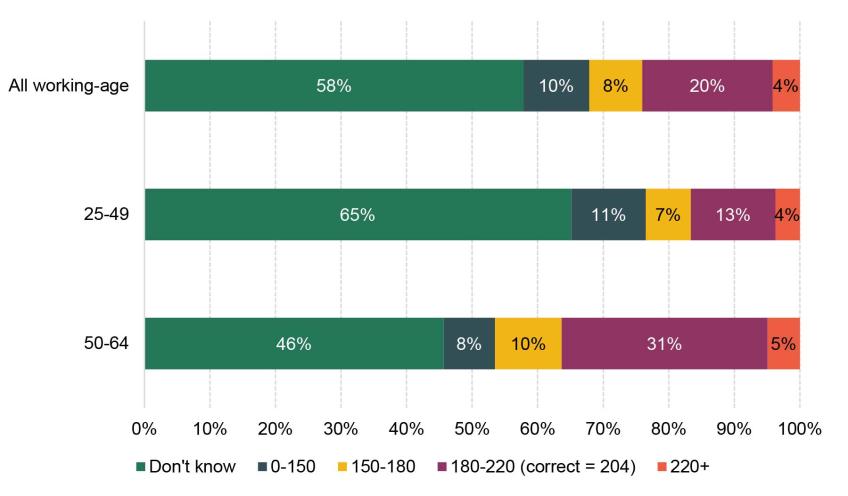

We have found only very limited understanding of pensions in the UK. Only 20% of people aged 25 to 64 could correctly state (to within around £20) how much a full state pension is worth in pounds per week. 58% said they did not know; with this being true of 65% for 25-49 year olds and 46% of for those aged 50-64. Almost all of the others thought that a full state pension was worth significantly less than its current £204 per week, fewer than one-in-twenty (wrongly) thought it was worth £220 a week or more.

Figure 1. Reported knowledge of current weekly full state pension amount (£ per week)

Note: the full new state pension is worth £203.85 per week in 2023-24. Source: YouGov polling of 3,145 25-64 year olds in June 2023.

Since 1975 the state pension has always been indexed to at least the growth in prices, with the current “triple lock” implying that it will increase each year by the greater of the growth in prices, earnings or 2½%. Despite this only 11% of people think that the state pension will have increased faster than inflation over the next 10 years, compared to 38% who said it would increase by less. This might suggest that few understand the impact of the triple lock – or perhaps don’t expect it to be in place for much longer.

While many will be unsurprised by this lack of knowledge, it is extremely important. For most people the state pension will be the single most important form of income in retirement, and people will only be able to plan their retirement finances well if they have some sense of how much the state pension will be able to support them. This confusion is borne out by the fact that fully two-thirds of people don’t know how high their income would need to be to have a reasonable standard of living in retirement and only 9% say they have good knowledge of pension issues.

There is much better understanding of the state pension age. 78% of people think that the state pension age will be more than the current 66 (in fact, it is set to rise to 67 by 2028). Significant numbers suggest they will retire in their late 60s, around when their state pension age is likely to be, – 19% expect to retire at 67, 10% at 68 and 12% at 70. This shows the salience of the state pension age which is highlighted frequently in the media.

Pessimism about retirement living standards and the future of the state pension

Despite lack of knowledge over the level of the state pension, there is widespread agreement that the state pension does not provide a reasonable standard of living in retirement, with 73% saying that it does not, compared to only 14% saying it does. These splits are pretty much unchanged across age, sex, social class and part of the country. Perhaps as a result of this, significant numbers of people say that their retirement income will not be good. 41% say they will have a bad retirement income, rising to 47% for people from the “C2DE” social class and the self-employed, both groups for whom private pension saving is lower.

Amazingly, people are so pessimistic that only 1 in 5 expect to be better off in retirement than their parents, with almost half expecting to be less comfortably off, even among 50-64 year olds (whose parents on average are likely to have accumulated much less wealth than them – see Sturrock 2023). Perhaps this is one sign that some of the pessimism may be over-stated and at least some will get a pleasant surprise when they reach state pension age and retire?

One particular form of pessimism relates to the state pension itself – a third of people think that the state pension will not exist in 30 years time, a view that is particularly common amongst those who reported voting Leave in 2016 and those who reported voting Conservative in 2019 (40% of both groups do not believe the state pension will continue to exist). The fact that the state pension is so important for many people’s retirement income means that it would be incredibly difficult – without enormous increases in private saving – to meet a good standard of living in retirement if the state pension or something similar did not exist. In many ways the state pension provides a “bedrock” for income in retirement, on top of which people can build private pension entitlement. Confidence in the state pension system is therefore important for people planning their pensions and retirement finances.

If retirement incomes are on course to be below par, who should pay more?

Retirement incomes – fundamentally – can only come from one of three sources. They can come from the state – paid for ultimately by taxpayers, either in this generation or future ones. They can come from employers, by making contributions to pension pots or promises of pension incomes. Or they can come directly from the individuals themselves, by putting away more each money in their pension, or in other forms of saving. To the extent that many will require or desire higher incomes in retirement than they are currently on track to receive, at least one of these sources would need to be increased to boost retirement living standards.

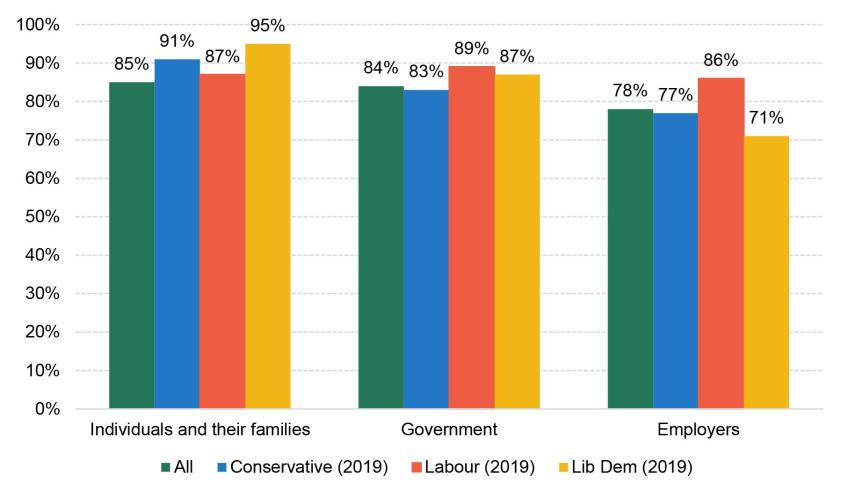

It is fair to say that there is some agreement in the public about where these extra contributions should come from. When asked about how much responsibility individuals/families; the government; and employers, have for providing a reasonable standard of living, almost 85% of people said that individuals and their families, and the government were responsible. This was followed closely by employers, at 78%. These numbers are all fairly similar across different parts of the population, albeit with some relatively small differences depending on who they voted for in 2019.

Figure 2. Percentage of working-age people who think that individuals and their families; government; and employers have a lot or a fair amount of responsibility to ensure people retire with a reasonable standard of living, split by 2019 General Election vote

Source: YouGov polling of 3,145 25-64 year olds in June 2023.

It seems like there could well be public support for policies that ask a least a little more from all three potential contributors. And although 61% of people say they are currently satisfied with their pension contributions from their employer, policymakers should think about how the state, employers and individuals might work together to boost retirement incomes. Indeed, 70% of people say that they would be likely (with 40% saying very likely) to contribute more if their employer matched their contributions.

Where next?

Many are pessimistic about their potential standard of living in retirement. This could be in part due to misperceptions of how well they are off compared to previous generations, not knowing – or under-valuing – the state pension, or a high degree of pessimism about the future of the state pension. So policymakers should look for ways to make the system simpler and to boost confidence in what people can expect from it. Working-age people also face competing financial pressures that makes prioritising pension saving difficult. Only 28% think that saving into a pension is one of their top three goals for saving (well below saving for a rainy day, or for expected expenses like buying a house or the financial costs of having children). It seems like relying – alone – on people making well-informed choices to save more for retirement is going to be hard. Finding solutions to these problems that recognise this lack of understanding, while still giving people support and flexibility to make choices that are more appropriate for them, seems like the right goal.