During any election campaign, a row between the political parties about who should pay tax - and how much - is certain.

They know that no voter wants to pay more, but they are also under pressure to fund manifesto pledges on public services.

Here's why it is so difficult to find the perfect balance.

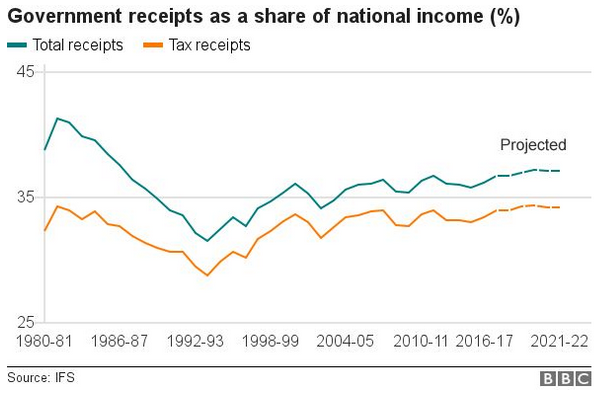

Money raised from taxes is nearing a historic high

For every £1 created in the UK through economic activity - that's the working, spending and saving that we all do - the government collects roughly 37p.

This adds up to about £700bn each year, which would be the equivalent of about £11,000 per person if the bill was split equally.

Tax is the most important part of this - the equivalent of 34p in every £1.

The rest of the government's income comes from a variety of sources. These include interest - for example on student loans; dividends - for example from holdings of Royal Bank of Scotland shares; and profits from assets - including the leasing of 4G mobile licences.

Taxes have increased since 2010 and in 2020 revenues are due to reach the highest share of national income since the 1980s.

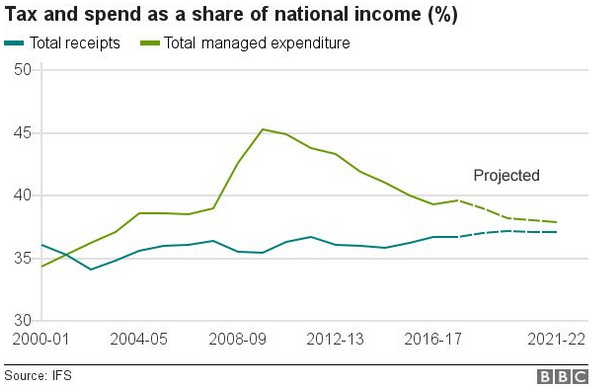

But there's still not enough money

It's usually the case that governments don't have as much money as they want to spend.

This year, for every £1 that it raises, the government will spend an extra 3p that it has borrowed.

This gap between spending and revenues is called the deficit, and the amount borrowed each year adds to the national debt.

The deficit increased substantially after the financial crisis of 2008, with attempts to limit it leading to large cuts to benefits and public services.

Any plans for spending cuts lead to controversy about the amount or quality of services.

But an ageing population and rising healthcare costs mean the government actually needs more money just to keep public services at their current level.

This is a massive challenge for any would-be government and means difficult choices between raising taxes and reducing spending.

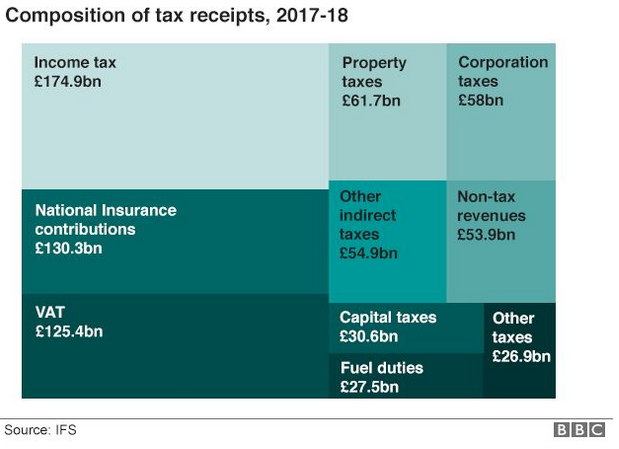

Where the government decides to get its money is important because it determines who is being made worse off.

The biggest chunk of overall revenue - about 40% - comes from income tax and national insurance contributions, both of which are based on your earnings.

Overall, this amounts to about £300bn.

This includes value added tax (VAT), which is a 20% tax on the cost of most things we buy, from pens and chocolate, to cars and fridges.

Some goods attract additional taxes, for example fuel, cigarettes and alcohol.

Higher income households pay the most

One of the key questions in any debate about tax is usually who's paying and who pays the most.

Based on income, the top half of households contribute 78% of combined receipts for income tax, national insurance, VAT, excise duties and council tax.

But this figure is actually an underestimate, because it relies on surveys that underestimate income tax paid by the highest income households.

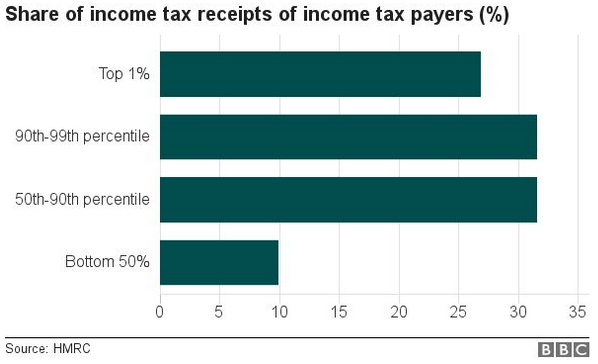

Tax returns are more reliable and show that income tax is very top-heavy.

The top 1% of those who do pay income tax are responsible for 27% of revenues. The top half pays 90% of income tax.

Four out of 10 adults pay no income tax because they are not working, or their income is too low. There is also a large system of benefits that increase the incomes of poorer households.

There are two reasons income tax revenues are so concentrated at the top: inequality and the way taxes are designed - there are higher rates for higher earners.

Taxes change over time

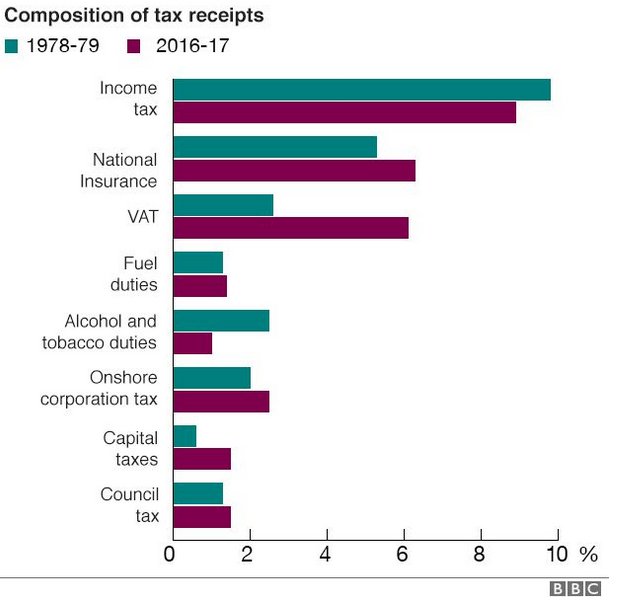

Politicians can decide what to tax and how high to set rates.

In recent years, policy changes have led to national insurance, VAT and capital taxes becoming more important sources of revenue.

Income tax, excise duties and corporation tax have become less important.

Tax revenues also vary because of the state of the economy. Some, like corporation tax, fluctuate with the economy more than others, like council tax.

Tax is all about trade-offs

No one likes paying tax and there is no harmless way to increase taxes - someone is always made worse off.

This is even true of taxes that target businesses, rather than individuals, because the costs will ultimately be passed on - for example through higher prices, lower wages for workers or reduced dividends for shareholders.

Taxes affect the choices individuals make, from how much to work, to how much effort to put in, how much to save and spend and what to buy.

For all governments, there are difficult choices about how to raise - and spend - the money they need, while limiting the damage done.

There is no easy answer.

Helen Miller is Associate Director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies. Follow her on @HelenMiller_IFS.

This article was first published on the BBC website and is reproduced here in full with permission.