This government has pushed geographic inequalities to the top of the policy agenda. In his very first speech as Prime Minister, Boris Johnson made clear his intent to boost economic performance outside of London and the South East, to ‘level up’ across the country and to revive the fortunes of the UK’s ‘left-behind’ towns and cities. This is an ambitious agenda, and one that will not be quickly achieved with off-the-shelf policy solutions.

In this chapter, we consider the evidence on UK regional inequalities and place them in international context. We then assess which areas might be classified as ‘left behind’ and in need of ‘levelling up’, and how this might be affected by the economic fallout from COVID-19 and Brexit. We consider the regional inequalities in four of the factors that are often cited in the context of levelling up: spending on investment, transport and R&D as well as in where civil servants are located. Finally, we examine some of the existing programmes aimed at targeting resources to left-behind places and discuss some of the issues and risks that the Chancellor should keep in mind ahead of this year’s Spending Review, which will be a chance to provide a road map for where, and how, this government plans to take its ‘levelling-up’ agenda forward.

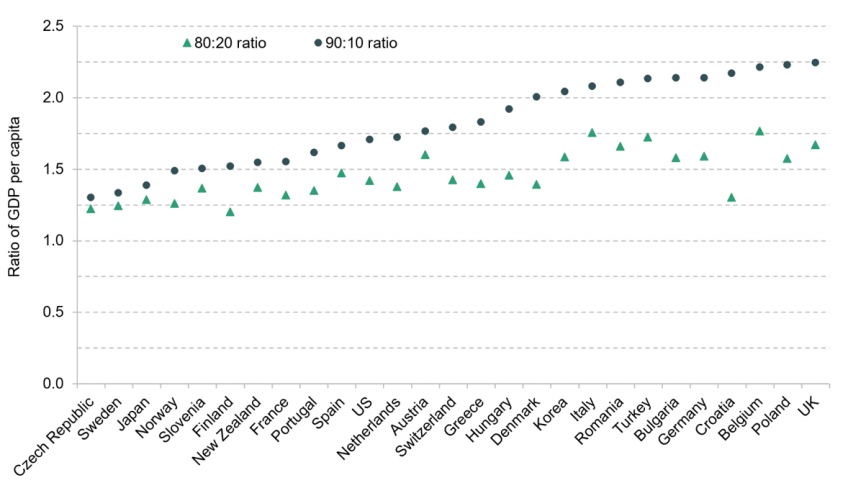

Measures of inequality in regional GDP per capita, by country

Note: Figures denote the ratio between GDP per capita in the 80th percentile ranked region and the 20th percentile ranked region (80:20), and the ratio between GDP per capita in the 90th percentile ranked region and the 10th percentile ranked region (90:10). Region defined as OECD ‘small’ (TL3) regions.

Source: Figure 7.1 in Chapter 7.

Key findings

1. The UK is one of the most geographically unequal countries in the developed world; compared with 26 other developed countries, it ranks near the top of the league table on most measures of regional economic inequality.

2. Neither the focus on nor the rhetoric around ‘levelling up’ is new, but reducing these spatial disparities is a stated priority of this government. The UK’s regional inequalities are deep-rooted and complex: even well-designed policies could take years or even decades to have meaningful effects.

3. There is no single set of factors that characterise a ‘left-behind’ place, and the government cannot be all things to all places. We combine measures of pay, employment, formal education and incapacity benefits to identify which areas might be considered ‘left behind’ and in need of ‘levelling up’. These areas can be found across the country, but left-behind places are particularly concentrated in large towns and cities outside of London and the South East, in former industrial regions, and in coastal and isolated rural areas.

4. We find that the traditionally ‘left-behind’ areas are not those most exposed to the short-term economic impact of COVID-19. This complicates the picture with regard to ‘levelling up’, since it introduces another dimension of geographic inequality. There are, however, important exceptions: a number of hospitality- and tourism-dependent coastal communities and the centres of some Northern and Scottish cities (such as Liverpool, Glasgow and Dundee), face the ‘double whammy’ of being both ‘left behind’ and vulnerable to the immediate economic fallout from the pandemic.

5. Brexit could make ‘levelling up’ more difficult. While the economic impact of Brexit remains highly uncertain, the options on the table are likely to impose a particularly high economic cost on some groups, such as less-educated male workers in blue-collar jobs. Many of these are concentrated in traditionally ‘left-behind’ areas in the North of England, South Wales and the West Midlands.

6. Currently, some sorts of public spending – transport and R&D, for example – are heavily concentrated in London and the South East. Increasing spending on these in other parts of the country might help with levelling up. But we should not forget that ‘current’ spending – especially on things such as schools and further education – may be as, if not more, effective.

7. There are at least eight existing place-based spending programmesrelevant to the ‘levelling-up’ agenda. These include the EU’s Regional Development Fund, which provides funding only until the end of this year. Rather than reinventing the wheel, the government could seek to build on these schemes, and develop a broader strategy around how they fit together. The Chancellor should also pay particular attention to the important role that local governments will play in ‘levelling up’.