Isabel Stockton, a research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said: “The response to the covid-19 pandemic has led to a sharp downturn in economic activity. It has also, rightly, prompted a substantial fiscal policy response, the cost of which will add directly to government borrowing. The outlook is uncertain to say the least. Only taking account of measures announced so far, and even if the economy “only” shrinks by 5% per cent this year, we might expect borrowing in the coming financial year to exceed £175 billion, or more than 8% of national income. This would be more than triple the amount forecast in the Budget just two weeks ago. About 40% of that increase would result from new fiscal measures, and the rest from the economic downturn depressing revenues and adding to government spending. The deficit could easily swell by much more than that if the economy shrinks by more, if take up of the employment retention scheme is high, or if further substantial fiscal measures are unveiled. A deficit of over £200 billion in the coming financial year is well within the bounds of possibility. Yesterday’s announcement in parliament to increase the contingency fund for the coming financial year from £10.6 billion to £266 billion suggests the government may be prepared to go even further than that.

Large increases in borrowing are well-advised to address the current crisis, but the consequences for the public finances will be felt long after the immediate public health emergency has hopefully passed. Debt which is already high by recent historical standards will jump up again and is likely to remain elevated for some time to come.”

Introduction

Lenin wrote that “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen”. That certainly feels the case with the two weeks that have passed since new Chancellor Rishi Sunak delivered his first Budget on March 11. In that period the public finance landscape has changed beyond recognition. The covid-19 pandemic is of course first and foremost a public health crisis, but its fiscal consequences will continue to make themselves felt for years – and more likely decades – to come.

Economic impact

The outbreak, and response to it, has led to a sharp economic downturn. Even before considering the substantial fiscal package that the government has committed to mitigating its impact, this will depress government revenues and increase spending. Morgan Stanley forecast (on Monday March 23) that the UK economy will contract by 5% this year due to the impact of the pandemic, which would leave it more than 6% smaller than forecast in the Budget two weeks ago. This estimate is predicated on a “robust” rebound in the second half of this year.

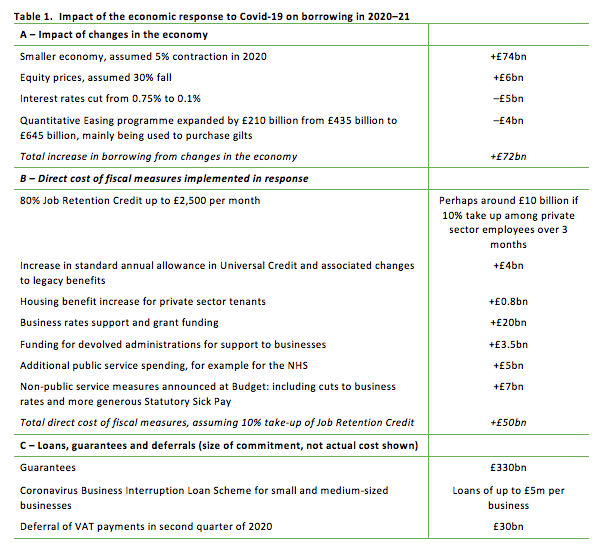

A rough rule-of-thumb suggests that this effect alone could add around £70 billion (3.2% of national income) to borrowing in the coming financial year (although it is possible some of this will arise in the subsequent financial year). This comes from falls in tax revenues (as company profits, earnings and spending are all reduced) and from rising spending on social security benefits. This latter effect is illustrated by yesterday’s news that in the last nine days 477,000 new claims have been made for Universal Credit – a daily rate of 53,000 which is an eight-fold increase on the typical 6,500 claims that the Department for Work and Pensions is used to getting each day.

In addition, equity prices have fallen sharply, which can be expected to depress revenue from stamp duty on shares, capital gains tax and inheritance tax. A further knock-on effect will follow as city bonuses, and withdrawals from accumulated defined contribution pension pots, are depressed.

The Bank of England’s decisions to reduce interest rates and expand its programme of Quantitative Easing will – very partially – counteract these effects by reducing the government’s recorded debt servicing costs further, from what is already a very low level by historical standards.

If the economy does shrink by around 5% this year these economic effects could likely add something like £70 billion (or 3.3% of national income) to government borrowing in the coming financial year. There is, of course, a tremendous amount of uncertainty around this number.

Direct fiscal giveaways

In addition to these economic effects, the government has committed to substantial amounts of support for affected businesses to allow them to stay afloat through both big cuts to business rates and the new employee retention credit for furloughed employees. In addition, it has implemented a substantial expansion of the social security system to support those who do lose their jobs or are unable to work. Additional funding has also been made available to support public services. Further support targeted at the self-employed will be announced today and yesterday’s announcement in parliament to increase the contingency fund from £10.6 billion to £266 billion suggests the government may be prepared to go even further.

The commitment to replace 80% of the wages of workers placed on furlough is impossible to cost with certainty in advance as we do not know how many private sector employers will take it up. If it were taken up by 10% of private-sector workers for a period of three months, it could cost around ten billion pounds. If more employers use the scheme, or for longer, it would of course cost proportionally more.

The government has also offered £330 billion of loan guarantees for businesses. These don’t count against borrowing this year as they are contingent liabilities. Given the scale of the economic hit, some part of them may crystallise in the future. Deferrals of VAT payments will at least delay receipt of £30 billion, and will put a fraction of that at risk.

Even at the, perhaps rather conservative, estimate in the table (for example the cost of the benefit increases will rise as the numbers claiming them increases sharply) and disregarding loans, guarantees and deferrals, the cost of which is unclear ex ante, the total package of additional spending would cost more than £50 billion, or 2.3% of GDP in 2020–21. This is already more than the dedicated UK fiscal response to the financial crisis, when the total UK fiscal stimulus package was 0.6% of GDP in 2008–09 and 1.5% of GDP in 2009–10.

Many other advanced economies have also implemented large packages of support or are planning to do so. However, many continental European economies also start from a more generous welfare system where benefits for short spells of unemployment replace a high fraction of previous earnings, instead of being means- and needs-tested, as has traditionally been the case in the UK. As a result the UK probably needs a larger bespoke package than some other countries.

Conclusion

Before the impact of the pandemic, the Office for Budget Responsibility forecast borrowing to be £55 billion, or 2.4 per cent of national income in the coming financial year. The full scale of both the economic impact of the covid-19 pandemic and the policy response to it will only become clear over time. But based on the information we have now, it would not be surprising if they were to add around £120 billion to borrowing, more than tripling the amount forecast just weeks ago and pushing borrowing up to £177 billion or 8% of national income. This would be more than 2008–09, but some way below its peak of 10.2% of national income in the following year. There is a substantial chance that borrowing will turn out considerably more than this if the economic hit is greater or a large fraction of private sector employers take advantage of the employment retention scheme.

Large increases borrowing are well-advised at the moment, to support households and reduce any long-term scarring effects in the economy. But as happened following the financial crisis, the changes in the public finance landscape that the outbreak has brought about will remain with us long after the immediate crisis has passed. By the end of 2020–21, we will have much-elevated government debt. Hopefully the Covid-19 outbreak will be behind us, but the tax and spend trade-offs facing policy makers will be made more stark for years, and more likely for decades, as they strive to bring debt back down over the longer-term.

A further piece setting out long-run scenarios for the public finances will follow in the coming weeks.

Carl Emmerson and Isabel Stockton

Sources: Economic impacts: author's calculations using Morgan Stanley, "UK Told to Stay at Home" (2020) and Office for Budget Responsibility, Tax and Spending Ready Reckoners (2019); job retention credit: IFS calculations using the Labour Force Survey; housing benefit: IFS calculations using TaxBen; other fiscal measures: HM Treasury.

Postscript: on Thursday 26 March, after this piece was written, the Chancellor unveiled a substantial package of support for the self-employed. The cost of this is uncertain but £10 billion over three months might be a reasonable ballpark estimate.