With the general election now just eight months away the political parties are starting to set out what they would aim to achieve in government. In this observation, we describe what each of the three main UK parties have said about their fiscal targets and discuss how these differ from current coalition government policy and from each other. Meeting the Conservatives’ target could result in debt falling more quickly than would be the case under the rules proposed by Labour or the Liberal Democrats. But doing so would require tax rises or significantly greater cuts in public spending than Labour and the Liberal Democrats would require to meet their rules – on top of those that are already planned up to 2015–16.

What are the government’s current plans?

The current government has committed to meeting two fiscal targets:

- The fiscal mandate states that the cyclically-adjusted current budget should be forecast to be in balance or surplus at the end of a rolling five-year forecast horizon.

- The supplementary target requires that public sector net debt should fall as a share of national income between 2014–15 and 2015–16.

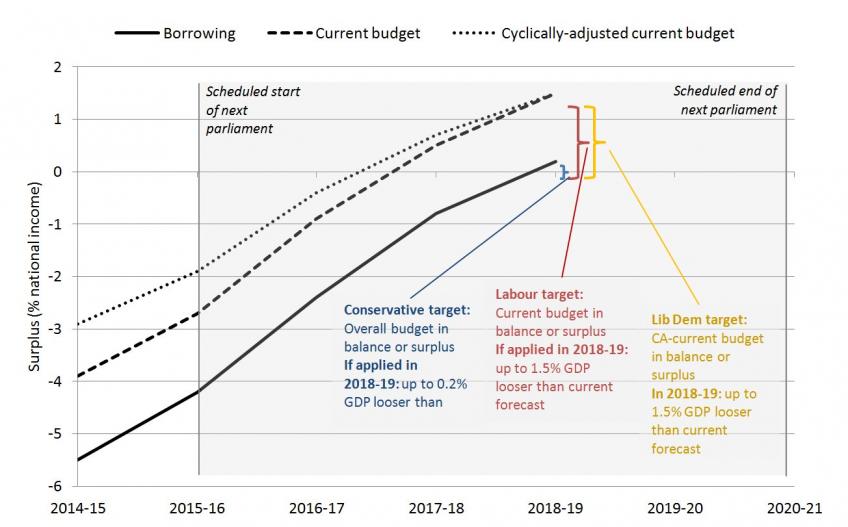

While borrowing over this parliament is on course to be substantially greater than the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast back in June 2010 the additional spending cuts pencilled in for the next parliament are sufficient for the latest official forecasts to suggest that the fiscal mandate is being met. Indeed, it is being met by some margin, with a surplus of 1.5% of national income (or £26 billion in today’s terms) forecast for 2018–19, which is currently the last year of the forecast horizon.

However, the latest OBR forecast suggests that the supplementary target is on course to be missed. Although borrowing is forecast to fall over the coming years, the OBR still expects public spending to exceed public revenues by a significant margin in the next few years and so the stock of public debt will continue to grow more quickly than the economy. As a result, the OBR forecasts that debt will rise from 77.3% of national income in 2014–15 to 78.7% in 2015–16, before falling slightly to 78.3% in 2016–17.

Table: Latest OBR forecasts for borrowing and debt

| 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | |||||

As % GDP |

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||

Current budget deficit | 4.9 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 0.9 | –0.5 | –1.5 | |||||

Cyclically-adjusted current budget deficit | 3.6 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 0.4 | –0.7 | –1.5 | |||||

Public sector net borrowing | 6.5 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 0.8 | –0.2 | |||||

Public sector net debt | 76.3 | 77.3 | 78.7 | 78.3 | 76.5 | 74.2 |

Source: Outturns for the current budget deficit, borrowing and debt in 2013–14 are taken from the ONS’ statistical bulletin Public Sector Finances, July 2014. Forecasts for borrowing and debt as a % of GDP are taken from Tables 4.39 and 4.43 of the OBR’s March 2014 Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

What are the Conservatives’ objectives?

What have they said?

At the Conservative party conference in September 2013, George Osborne set out his party’s objective of achieving an overall budget surplus. Specifically, he committed that “provided the recovery is sustained, our goal is to achieve that surplus in the next Parliament.”

So far, the Conservative party have made no specific commitments on the path for debt, aside from those signed up to (but currently on course to be missed) by the current coalition government. However, since future debt depends on future levels of borrowing, the commitment to achieve an overall budget surplus will imply something about the future path of debt – exactly what it implies will depend on how quickly they reach a surplus and how large a surplus they achieve.

How does this compare to current government policy?

The major difference between what the Conservative party would aim to achieve and the coalition’s fiscal mandate is that the Conservative party want to achieve an overall budget surplus – rather than just a surplus on the current budget. In other words, the Conservatives want to ensure that government revenues are sufficient to pay not only for current spending but also for investment spending.

The latest OBR forecast suggests that current government policy is consistent with the Conservatives’ objective of achieving an overall surplus in 2018–19, albeit with a small margin of error. Specifically, the March 2014 OBR forecast was for public sector net investment in 2018–19 to be 1.4% of national income, and therefore for public sector net borrowing to be –0.2% of national income (i.e. in surplus).

However, the latest forecasts for the public finances imply further deep cuts to public service spending, which have not yet been set out in any detail. To achieve the currently forecast levels of borrowing, without any further tax increases or cuts to welfare spending, the government would need to cut spending by government departments by a further 10.6% in real terms (or £37.6 billion) between 2015–16 and 2018–19. This is on top of the £8.7 billion cut that has already been set out for 2015–16.

What are Labour’s objectives?

What have they said?

In January 2014, Ed Balls set out Labour’s objectives for the fiscal position. As he said then, Labour’s objective is to “deliver a surplus on the current budget and falling national debt in the next Parliament”.

How does this compare to current government policy?

Labour’s first target relates to the current budget balance. The main difference between Labour’s target and the fiscal mandate is that Labour have committed to delivering a balance or surplus on the current budget at some point in the next parliament, whereas the fiscal mandate instead requires that the cyclically-adjusted current budget must always be forecast to be in balance or surplus after five years. A second difference between Labour’s target and the fiscal mandate is that the former targets the headline current budget balance, whereas the latter relates to the cyclically-adjusted measure.

Labour have not been precise about exactly when they would seek to deliver a surplus, or how large a surplus they would aim for. Ed Balls said that “How fast we can go will depend on the state of the economy and the public finances we inherit.”

The OBR’s latest forecasts suggest that, on current plans, the current budget will reach a surplus (of 0.5% of national income) in 2017–18, increasing to 1.5% of national income in 2018–19. Unless Labour seek to deliver as large a surplus as this (or larger), their target potentially implies a looser fiscal position than current policy – that is, they may be able to cut taxes or increase spending relative to current policy by 1.5% of national income in 2018–19. For example, if Labour chose to achieve exactly a current budget balance in 2018–19 and allocated all the extra borrowing to easing the planned cuts to departmental spending (rather than to tax cuts or increases in benefit spending), then the cumulative cut required to departmental spending would be reduced from £37.6 billion to £9.3 billion (or 2.6%) between 2015–16 and 2018–19.

The OBR’s latest forecasts also suggest that Labour could operate somewhat looser fiscal policy than current government policy and still achieve their target of debt falling within the next parliament, since the latest forecasts are for debt to fall from 2016–17 onwards.

What would the Liberal Democrats do?

What have they said?

The Liberal Democrats have stated that they will seek to balance the cyclically-adjusted current budget from 2017–18 onwards and to “significantly reduce national debt as a percentage of GDP, year on year, when growth is positive, so that it reaches sustainable levels around the middle of the next decade.”

How does this compare to current government policy?

The Liberal Democrats’ first target (to achieve a cyclically-adjusted current budget balance from 2017–18) relates to the same measure of borrowing as the fiscal mandate. It differs from the targets discussed by Labour and the Conservatives in that they plan to target a measure of borrowing that explicitly attempts to abstract from temporary strength or weakness in the economy. On the other hand, both the Conservatives and Labour have alluded to similar allowances for the economic cycle when discussing their targets, as they have suggested that whether and exactly when their targets would be achieved would be dependent on the state of the economy. The latest OBR forecasts suggest that the output gap will close in 2018–19, meaning that cyclically-adjusted measures of borrowing are almost exactly the same as headline measures of borrowing in that year (as shown in the Figure). As a result, achieving the Liberal Democrat target for a cyclically adjusted current budget balance implies almost exactly the same thing in that year as achieving Labour’s target of a headline current budget balance.

Current government policy is, according to the OBR’s latest forecast, consistent with achieving a cyclically-adjusted current budget surplus of 0.7% of national income in 2017–18 and 1.5% in 2018–19. Therefore, similar to Labour, the Liberal Democrats’ commitment could be consistent with running looser fiscal policy than the government is currently planning. For example, if the Liberal Democrats chose to achieve exactly a cyclically-adjusted current budget balance in 2018–19 and allocated all the extra borrowing to easing the planned cuts to departmental spending (rather than to tax cuts or increases in benefit spending), then the cumulative cut required to departmental spending would be reduced from £37.6 billion to £8.6 billion (or 2.4%) between 2015–16 and 2018–19.

The Liberal Democrats’ target for debt is consistent with the latest OBR forecast on the basis of current government policy, as outlined above.

Summary

The parties’ fiscal targets differ from one another and from the current government’s objectives and plans in two main ways. First, the exact measure of “borrowing” that is targeted differs. Second, the timescale over which a surplus must be achieved varies – for example, the current government’s fiscal mandate is explicitly forward looking with a rolling five-year target, while each of the three parties’ proposed new targets for borrowing seem to relate to a fixed date – that is, all of them refer to achieving the objective during the next Parliament. There are strong arguments in favour of forward-looking, rather than fixed date, targets and all the parties would be well advised to consider rephrasing their objectives in this way.

The Figure below illustrates how the different measures of borrowing being targeted differ from one another. The Conservatives and Labour have not yet been specific about when exactly they would seek to achieve budget balance. The latest OBR forecasts only run to 2018–19 but there would be one further full financial year in the next parliament, assuming it begins in 2015–16 and runs its full 5-year course.

The targets chosen by Labour and the Liberal Democrats would, in principle, allow them to have a higher level of spending and/or lower level of taxation than the Conservatives would require to meet their target for borrowing. However, for both Labour and the Liberal Democrats this would, of course, come at the cost of debt declining less quickly as a share of national income than implied by either current government projections or the Conservatives’ fiscal target.

For all the main UK parties, based on the latest official forecasts for the economy and public finances, achieving their fiscal targets will require further tax increases, or cuts to welfare spending or public services in the next parliament. None of the parties have yet provided the electorate with full details of these tough choices.

Figure: Comparing the parties’ fiscal targets

Glossary