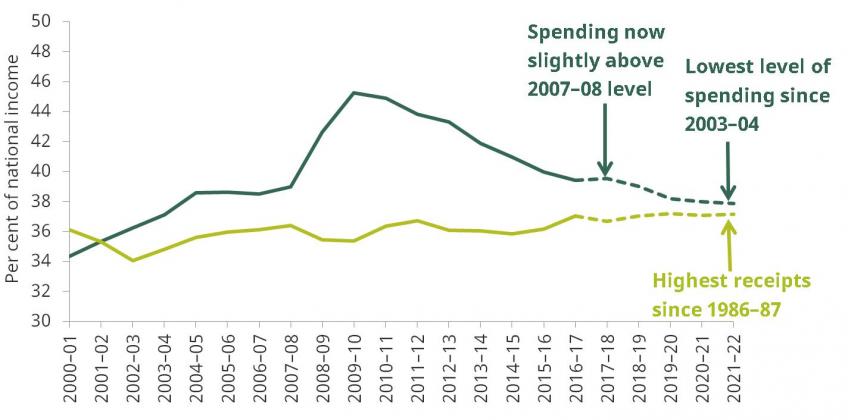

Terrible economic growth since the start of 2008 has created big problems for the finances of both households and government. The government’s deficit increased from 2.6% of national income to a post Second World War high of 9.9% of national income in 2009–10. The period of “austerity” since then has been focussed on getting that deficit down through a combination of some net tax rises and some big cuts to benefits and spending on public services. The deficit stood at 2.4% of national income in 2016–17. So the UK now has a smaller government deficit than prior to the financial crisis. Tax is higher as a share of the economy than it was in 2007–08. Perhaps more surprisingly public spending also now takes a slightly larger fraction of national income than it did in 2007–08. All that austerity has got us back to where we were, in terms of spending overall, ten years into the last Labour government’s term of office. The problem has been that the economy is far far smaller than expected.

Despite the UK’s weak economic performance over the last decade the Office for Budget Responsibility judges that there is currently no spare capacity in the economy. If correct this means we can’t rely on above normal levels of growth helping bring the deficit down further. Therefore the commitment made by Chancellor Philip Hammond in last November’s Autumn Statement to deliver a budget surplus “as early as possible in the next Parliament” was expected to require a combination of further tax rises and spending cuts.

The plans of the previous Conservative Government in the March 2017 Budget are shown in the figure below. The tax burden was forecast to continue rising – climbing to its highest level since the mid 1980s – driven by further tax raising measures such as an increase in dividend tax and council tax rises (earmarked for spending on social care). The net effect of these discretionary tax measures is to boost revenues by a further £5 billion in 2021–22.

March 2017 Budget forecast for tax and spend

Public spending is forecast to continue falling as a share of national income. In part this results from planned cuts to benefits – mainly targeted at working age benefits – that are already in the pipeline. This includes a freeze to the rates of most working age benefits in April 2018 and April 2019 and also the effect of more new claimants moving onto Universal Credit (which is now less generous, on average, than the system it replaces) and more new births in large families (who no longer see a boost to means-tested benefit entitlements if they already have two children). In total these benefit cuts will reduce spending by a further £11 billion in 2021–22, and by more in the longer-term.

There is also a continued squeeze on the share of national income devoted to public service spending (defined here as total spending by government less that spent on benefits, state pensions and debt interest). Over the five years from 2016–17 to 2021–22 this is forecast to rise in real terms by £37 billion, with a £23 billion increase in day-to-day spending and a £14 billion increase in investment spending. These real increases equate to a fall in spending as a share of national income equivalent to £17 billion by 2021–22. Within this there is considerable variation: day-to-day spending is to fall as a share of national income by £27 billion while investment spending is forecast to rise by £10 billion. The spending cuts are far from evenly shared across departments: for example while the Ministry of Justice faces further budget cuts the Department for International Development’s budget continues to rise.

While the effect of spending cuts so far has been to bring public spending down to its pre-crisis level as a fraction of national income, current plans imply further cuts such that overall public spending will reach its lowest share of national income since 2003–04 in 2019–20.

So far the policy announcements by the Government do not amount to a significant change in fiscal policy. The additional spending for Northern Ireland, while sizable in the Northern Irish context, are not a big deal for the UK public finances while the abandonment of plans to means-test Winter Fuel Payments and to move, from April 2020, from “triple” to “double” lock indexation of the state pension would not have cut spending by much in the current parliament.

Targets

The Conservative Party manifesto watered down the previous commitment on the deficit to targeting a “balanced budget by the middle of the next decade”. As shown in the figure above the latest forecasts imply that this would require some combination of further tax rises and spending cuts beyond 2021–22. Continued ageing of the population, with the large generation born just after the Second World War putting an increasing strain on the NHS and social care budgets over this period, will make that all the harder to achieve. Brexit adds an additional layer of uncertainty.

On the other hand this target will not bite for a while. The new Government could therefore choose to pursue a looser fiscal policy than currently planned in the short term while claiming still to be heading for budget balance at some point in the 2020s. But given the scale of the takeaway planned for the next few years an “end to austerity” – as defined by no further net tax rises, benefit cuts or cuts to spending on public services – would require a very sharp change of direction. It would imply a £17 billion boost to planned spending on public services alongside a £5 billion net tax cut and an £11 billion increase in planned benefit spending – i.e. a giveaway of £33 billion a year. What that would do would, on current forecasts, leave us with a deficit at its current level – 2.4% of GDP – in 2021–22. That is an option in a way that it was not an option back in 2010.

We could choose to continue to run deficits of around the current level over the longer-term. If the economy were to grow as expected this would be sufficient to see debt fall as a share of national income over the longer term. It would mean that over the next few years household incomes could be better supported and a greater quality and quantity of public services could be enjoyed. But it would also involve planning to live with elevated public sector debt for longer. It could give the chancellor less room for manoeuvre if the economy were to suffer badly, for Brexit related or other reasons over the next few years; and it would almost certainly require the abandonment of the pledge to eliminate the deficit in the mid-2020s.

If instead the concern was with public spending cuts – rather than overall austerity – then an alternative option would be to raise taxes in order to reduce the planned cuts to spending on public services as a share of national income or to reduce the scale of the benefit cuts currently in the pipeline. To give one example the government could choose not to implement the planned cut to the corporation tax rate from 19% to 17%. That would raise an additional £5 billion which could be spent on public services or reducing benefit cuts, without affecting the deficit. Other tax increases are of course available.

As ever the chancellor has choices and as ever there are trade-offs. He could decide to spend and borrow more; he could decide to spend and tax more; or he could decide to stick with his current plans and see spending continue to fall. He is not going to be able to give everyone everything they want and the sooner he makes plain what his choices are the better for all.

This observation is based on a presentation by Carl Emmerson which wis given at an Institute for Fiscal Studies / Institute for Government joint event on “What next for tax and spend?” July 12 2017.