This briefing note analyses the Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat plans for public sector pay, and what the implications of their policies are for the public sector.

IFS Election 2017 analysis is being produced with funding from the Nuffield Foundation as part of its work to ensure public debate in the run-up to the general election is informed by independent and rigorous evidence. For more information, go to http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org.

Key findings

- The current Conservative government’s policy is for public sector pay scales to rise on average by 1% each year up to and including 2019–20. Public sector pay scales have risen by 1% per year every year since 2013–14. There were also freezes for all but the lowest paid public sector workers in 2011–12 and 2012–13.

- The Labour Party and Liberal Democrats have announced in their manifestos increases in public sector pay compared to current government policy. The Liberal Democrats would increase public sector pay in line with inflation. The Labour party would delegate public sector pay setting to Pay Review Bodies.

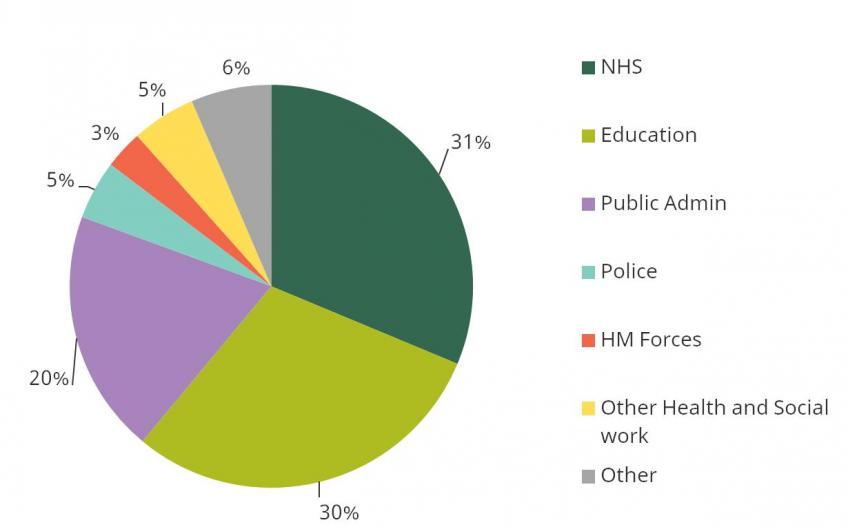

- Increasing public sector pay would boost the earnings of the 5.1 million public sector workers, 1.6 million (31%) of whom work for the NHS, and 1.5 million (30%) who work in education in the public sector.

- Public sector pay rose compared to private sector pay during and after the 2008 recession, as private sector earnings fell sharply in real terms. Public pay restraint since 2011 has led to the difference between public and private sector pay returning to its pre-crisis level. The latest reports from Pay Review Bodies, particularly those covering the NHS and school teachers, are reporting problems recruiting and retaining staff.

- In the long run, public sector pay will need to rise in line with private sector pay for the public sector to attract the skilled individuals needed to administer and deliver public services. Under current government plans, and given current OBR forecasts, the difference between public and private wages would fall to a level not seen in (at least) the last 20 years. Under the Labour plans, the difference would stabilise around the level seen in the mid 2000s. The Liberal Democrat plans would be below the level seen in the early 2000s, when there were significant shortages of nurses.

- Our analysis of the Labour plan implies that, compared to the current government’s plans, by 2021–22 a Labour government would need to provide departments and local government with an additional £9.2 billion per year to pay for the higher costs of employing public sector workers. Of this, £2.9 billion would be for the NHS. Comparing the Liberal Democrats’ plans to the current Conservative government’s plans, it would necessitate an extra £5.3 billion per year, of which £1.6 billion would be for the NHS.

- This analysis shows there are tradeoffs in delivering public services. Increasing public sector pay involves large increases in costs for government departments. However, if public sector pay continues to fall compared to pay in the private sector, the public sector will struggle to recruit and retain the workers it needs to deliver public services, and the quality of those services will therefore be at risk.

In the Summer Budget 2015, the Conservative government announced that annual pay awards in the public sector for the four years from 2016–17 to 2019–20 would average only 1% per year. This period of pay restraint came on top of 1% increases in each year from 2013–14 to 2015–16 and cash freezes for all but the lowest paid public sector workers in 2011–12 and 2012–13.

The Labour Party and the Liberal Democrat parties have in their respective manifestos pledged to raise public sector pay faster than is currently planned by the government. The Labour party manifesto pledges to “end the public sector pay cap”. Other statements from Shadow ministers imply that this means returning to increasing pay in line with the recommendations of Pay Review Bodies.[1] The Liberal Democrat manifesto says it would “lift the cap on public sector pay” by increasing wages in line with inflation instead of the 1% per year up to 2019–20.

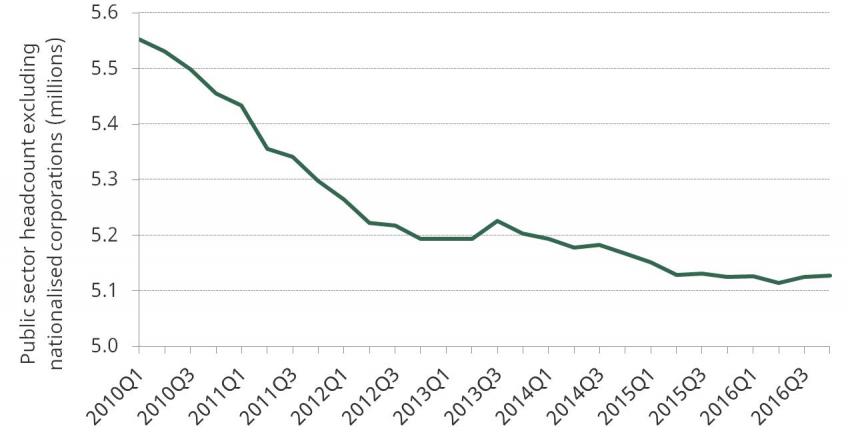

Increasing public sector pay would directly raise the pay of just over 5.1 million people who work for central or local government. As Figure 1 shows, since early 2015 the public sector workforce has barely changed, although there has been a large decline of around 400,000 (8%) since 2010Q1. Most of this fall in public sector employment occurred between 2010 and mid 2012.

Figure 1. Public sector workforce headcount excluding nationalised corporations

Note: Public sector headcount excluding nationalised corporations is also known as general government employment. Excludes the impact of reclassification of English FE and Sixth Form colleges to the private sector in 2012. Source: Author’s calculations using the ONS Public sector employment statistics.

The largest single part of the public sector workforce, is the 1.6 million NHS employees, which makes up 31% of the workforce, as is shown in Figure 2. The next biggest is the 1.5 million workers in education in the public sector[2] (30% of the total), and the 1.0 million strong public administration (civil service and local government administration) workforce which makes up 20%. Smaller public sector workforces include police, HM Forces and those undertaking public sector health and social work outside the NHS. It is these three areas- along with public administration- that saw the largest falls in their workforces in the 2010-2012 period.[3]

Figure 2. Proportion of public sector workforce working in each area of public sector 2016 Q4

Note: Public sector employment excludes nationalised corporations (also known as general government employment). Source: Author’s calculations using the ONS public sector employment statistics.

When determining how much to increase public sector pay, it is important compare the pay of public sector workers to the pay they could earn in the private sector. Ultimately, if public sector pay does not keep up with private sector pay, some will choose to work in the private sector rather than the public sector, causing recruitment and retention issues and making it harder to deliver high quality public services.

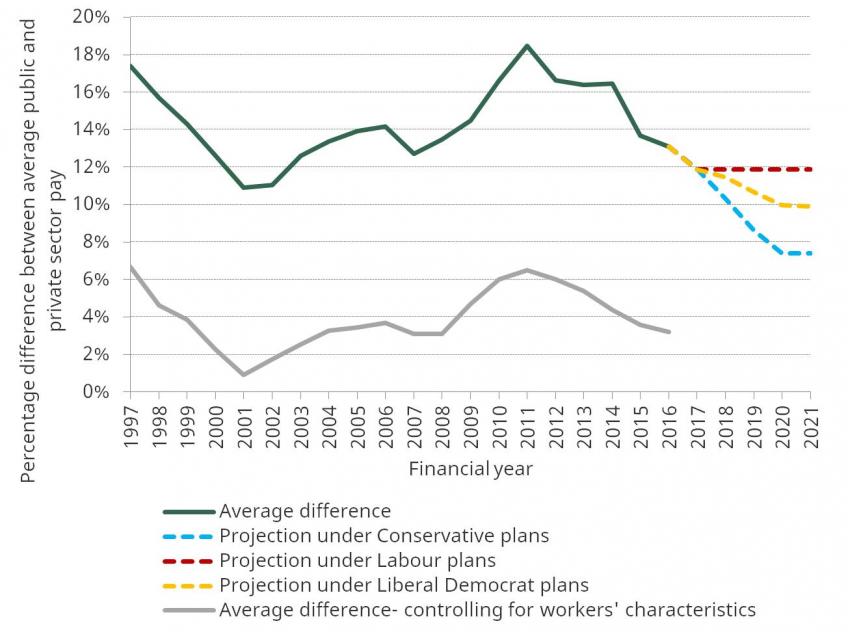

Figure 3 shows how the difference between public sector and private sector pay has changed since 1997. The dark green line compares average hourly pay in the public sector to that in the private sector. It shows that in 2016–17, average public sector pay was 13% higher than private sector pay. The grey line makes some adjustments for the types of workers in each sector. Primarily because the public sector is mainly staffed by highly educated professionals, once adjusting for observed differences in a set of workers’ characteristics, the estimated pay differential is much smaller.[4]

The Figure shows that public sector pay rose relative to private sector pay after the recession, as private sector pay fell sharply in real terms. The public sector pay restraint imposed since 2011 has returned the difference between public and private pay to around its pre-crisis level. However, after multiple years of pay restraint, a number of Pay review Bodies, particularly the NHS and School Teachers Pay Review Bodies have cited that pay restraint is leading to problems of recruiting and retaining the staff that are needed, and motivating the staff that are working there.[5]

Figure 3. Difference between average public and private sector pay, including projections under different parties’ policies

Notes: Data to 2016–17 estimated using Labour Force Survey data (2016–17 only includes up to 2016Q4). Difference controlling for workers characteristics controls for differences in age, sex, education, experience and region. Projections based on author’s calculations using OBR Economic Fiscal Outlook March 2017, Labour Manifesto and Liberal Democrat manifesto. We assume that a Labour government delegating public sector pay to pay review bodies will lead to them increasing public sector pay at the same rate as private sector pay. We interpret Liberal Democrat policy to be to increase in public sector pay in line with expected CPI inflation in 2018–19 and 2019–20, and delegate decisions to Pay Review Bodies after that.

Using the Office for Budget Responsibility’s latest forecast for earnings growth, and the plans set out in manifestos, we can project the difference between public and private sector pay in coming years. Under the Conservative plans, private sector pay would rise 6 percentage points faster than public sector pay between 2016–17 and 2020–21. This would reduce the average difference between public and private sector pay to a level not seen in (at least) the last 20 years; well below the level seen in the early 2000s when there were shortages of nurses. Given that Pay Review Bodies are currently reporting recruitment and retention problems, the Conservative plans are likely to exacerbate such problems, which could damage the quantity and quality of public services delivered.

The Liberal Democrats’ plans also imply that public sector pay will not rise as fast as private sector pay. Although, the fall in the relative level of public sector pay would not be as large as that under the Conservatives, it would still take the difference to below the level seen in the early 2000s. We assess that, if public pay setting is delegated to Pay Review Bodies by the Labour Party, the Pay Review Bodies would be likely to increase public sector pay in line with private sector pay, therefore stabilising the difference around its pre-crisis level. By not committing to specific rates of public sector pay growth over the next few years, one advantage of the Labour plan is that it allows public sector pay to respond flexibly to the state of the labour market. On the other hand, the Conservative plan of specifying 1% growth in pay scales in 2018–19 and 2019–20 provides certainty to public sector employers regarding their costs.

In 2016, the public sector paybill (excluding nationalised corporations) was £179 billion. This includes the wages and salaries of public sector workers, the employer National Insurance Contributions, and employers’ pension contributions towards public service pension schemes. With such a large paybill, even small percentage increases can lead to significant increases in the cost of employing public sector workers.

Table 1 shows the estimated increase in employment costs to central and local government as a result of the Labour and Liberal Democrats’ plans, compared to the current Conservative government’s policy of 1% increases until 2019–20. These costs include the amount that public sector employers would need to pay in terms of higher employer National Insurance and pension contributions. The figures therefore show the extra amount that departments and local government would need to receive in funding to pay for the higher wage bill, without having to make any offsetting cuts either to the size of the workforce or to non-wage costs.

It shows that by 2019–20, if public sector pay rose at the same rate as private sector pay under the Labour plan, a Labour government would need to provide departments and local government with an additional £6.3 billion per year compared to under the current Conservative government’s plans. That increases to £9.2 billion per year by 2021–22. Of this, roughly one-third of the increase would need to go to the NHS, or an increase in funding of £2.9 billion per year by 2021–22. For the Liberal Democrats, the necessary funding increases are smaller, of £4.1 billion per year in 2019–20, rising to £5.3 billion per year in 2021–22. Again, roughly a third of this would need to go to the NHS, totalling £1.6 billion per year in 2021–22.

These Figures are highly sensitive to the forecasts of the economy. For the Liberal Democrats, the cost will be higher if inflation is higher in 2018–19 and 2019–20 than is expected by the OBR currently, or lower if inflation is lower. Under Labour’s policy if private sector earnings growth performs less well over the coming years than is forecast by the OBR (it has consistently underperformed OBR forecasts in recent years), then it would cost less than is implied by Table 1. Conversely, if private sector earnings growth performs better than forecast, and public pay is increased faster too, then the cost to departments and local government of Labour’s policy would be higher too.

Table 1. Estimated increase in funding needed for central and local governments to increase public sector pay under Labour and Liberal Democrat plans compared to current Conservative government policy

| Increase in required funding per year for central and local government in: | |

| 2019–20 | 2021–22 |

Labour | 6.3bn | 9.2bn |

Of which: NHS | 2.0bn | 2.9bn |

Liberal Democrat | 4.1bn | 5.3bn |

Of which: NHS | 1.3bn | 1.6bn |

Source: Author’s calculations using ONS series NMXS (Total Compensation of general government employees), Office for Budget Responsibility Economic and Fiscal Outlook March 2017 and Labour and Liberal Democrat party manifestos.

Summary

Since 2011, there has been significant pay restraint in the public sector. For a number of years this was achieved without significant recruitment and retention issues, probably because public pay had done so much better than private sector pay during the recession. However, these pressures are emerging now, and could harm the quality of public services. There are significant trade offs in the future setting of public sector pay. Restraining public sector pay compared to the private sector, as proposed by the Conservatives, and – to a lesser extent by the Liberal Democrats –risks exacerbating recruitment, retention and motivation problems and ultimately the quantity and quality of public services provided.

On the other hand, increasing public sector pay results in significantly higher costs to public sector employers compared to the current Conservative government’s plans. The next government could decide to increase departmental spending to account for these higher costs of paying public sector workers. But if it did not provide extra funds, departments would need to make cuts elsewhere – for example by further reducing the number of public sector workers, cuts that may themselves reduce the quality of public services.

Notes

[1] See the speech by Jon Ashworth, Shadow Secretary of State for Health to Unison conference on April 26th 2017: http://press.labour.org.uk/post/160008381504/jonathan-ashworth-shadow-health-secretary-speech

[2] Note that the public sector education workforce does not include universities, which are not public sector institutions

[3] For more information, see Figure 2b in Cribb, Disney and Sibieta (2013) “The public sector workforce, past, present and future” https://www.ifs.org.uk/bns/bn145.pdf

[4] These figures do not include non-pay remuneration, such as pensions, which are still much more generous on average in the public sector than the private sector, despite cuts in their value since 2010.

[5] See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-teachers-review-body-26th-report-2016 and https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-health-service-pay-review-body-30th-report-2017