In his final Budget before the General Election, George Osborne confirmed the next step on his journey to provide greater flexibility in how people can access their defined contribution (DC) pension savings: removing the tax penalty that currently applies to anyone who wants to sell their existing annuity.

On the face of it, this appears to provide welcome new flexibility for the estimated 5 million people who currently receive income from a DC annuity in the UK. But it is not clear that this reform will move us to a new utopia for those who have already purchased annuities.

First, potential purchasers may – for reasons not simply related to a desire to make a profit at the expense of the seller – not be willing to pay a price for annuities that sellers will be willing to accept. Second, there could be pitfalls if annuity holders are not able to make well-informed decisions about whether to sell or not. Finally, part of the animosity towards the old ‘compulsory annuitisation’ requirement was driven by a (not always well-evidenced) belief that annuities offered poor value for money – indeed the government’s consultation last year on removing the compulsory annuitisation requirement stated that “the annuities market is currently not working in the best interests of all consumers. It is neither competitive nor innovative and some consumers are getting a poor deal”: but, if the market for selling annuities was perceived not to work well, it is far from clear why a market for buying them back should work much better.

At present, if someone sells an annuity that they have already bought with funds from a DC pension, they face a tax charge of up to 55% (or 70% in some cases). Budget 2015 proposed that, from April 2016 onwards, people will be able to sell their annuity and pay tax at their marginal rate when they draw on the sale proceeds. The government is consulting on a number of issues, including how the secondary market for annuities should operate and what advice and guidance should be provided to potential sellers. Both are important questions.

Who will be affected by the change?

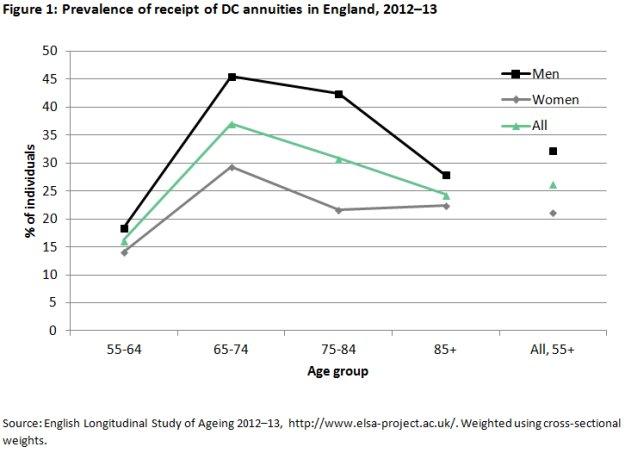

The government estimates that in 2013 there were 5 million people receiving DC annuity income totalling £13 billion – making the potential size of the secondary market for annuities significant. Using data from a representative survey of the older English household population, Figure 1 shows that 1 in 4 people aged 55 and over receive income from a DC pension annuity. This fraction varies significantly by age and sex: 1 in 7 women aged 55–64 fall into this group, compared to nearly half of men aged 65–74. The higher prevalence of DC annuities among those aged 65–74 than among older people reflects the relatively recent emergence of DC pensions, which means that fewer individuals in earlier cohorts will have saved any money in a DC pension.

Annuities pay out money until the annuity holder dies (or, in the case of joint life annuities, until they and their partner have both died). Therefore, an annuity will be ‘worth’ more if the person is expected to live for a long time, and less if they are expected to die soon.

Table 1 shows an estimate of the value of the annuities held by people aged 55 and over in England, based on the assumption that each person lives to the average life expectancy for their gender for people born in the same year. This is likely to understate the true ‘value’ of these annuities since – as Finkelstein and Poterba (2002) showed – annuitants live for longer, on average, than non-annuitants.

Table 1: Estimate value of DC annuities in payment (£)

| 25th percentile | Median | 75th percentile | |

| 55–64 | 12,503 | 28,299 | 72,713 |

| 65–74 | 11,912 | 29,114 | 69,812 |

| 75–84 | 9,148 | 23,112 | 52,349 |

| 85+ | 4,568 | 15,002 | 31,894 |

| All, 55+ | 10,665 | 25,854 | 61,766 |

Note: Estimated values are calculated as the discounted present value of the annuity stream, using a real discount rate of 3% a year and assuming that each individual lives to their age- and sex-specific cohort life expectancy, as estimated by the Office for National Statistics. These calculations also make the simplifying assumption that all annuities in payment are single life, rather than joint-life, annuities.

Source: English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, 2012–13. Weighted using cross-sectional weights.

Using this method of estimating the ‘value’ of annuities, we estimate that the median value of future income streams from annuities in payment is nearly £26,000. The value of annuities is lower among older people than younger people, which is because older individuals have fewer years left to live. There is a significant range, however, in the estimated value of annuities in payment – 1 in 4 are estimated to be worth less than £11,000, while 1 in 4 are worth more than £61,000.

Will there be a market for selling annuities?

The estimates of the value of annuities shown above assume that all annuity holders are expected to live to their age- and sex-specific life expectancy. However, not everyone will – some will live longer, some will live less long and both the individuals themselves, as well as the companies seeking to buy the annuity, may have differing views on how much this is the case.

If many of those looking to sell an annuity are those who have good reason to believe they might die soon, and if those buying the annuity cannot fully reflect this in the price (either because they do not have full information or because they are legally prevented from using some information), then prices on offer will assume that those looking to sell will be likely to die soon. These prices will be unattractive to many potential sellers. This is an issue that arises in many insurance markets and is known as ‘adverse selection’.

There are good reasons to think that annuity sellers will have more information about their potential longevity than potential purchasers are able to reflect in the prices they offer. First, women, on average, live longer than men but it may well be illegal for purchasers to offer prices that vary by sex: meaning that the resulting market will be particularly unattractive to women. Second, individuals may well have better information about their survival chances than potential purchasers can hope to elicit. For example, they know more about their own lifestyle choices (such as how much exercise they do, and how much alcohol, tobacco and unhealthy food they enjoy), detailed family histories of disease, and whether they suspect they might be developing health problems that have not yet been diagnosed. For these reasons, the secondary market for annuities might be limited or even difficult to establish at all.

Making good decisions

The argument just outlined assumes that individuals are reasonably well-informed and are capable of making complex financial decisions of the type required in deciding whether or not to sell an annuity. But valuing an annuity versus a lump sum is a complex calculation and requires people to grapple with uncertainty surrounding their own longevity, potential future investment returns and inflation. Therefore, a further concern with this policy might be that some annuity holders are not well-placed to make such decisions and may – as a result of this policy change – make a choice that is to their detriment.

Table 2: Financial decision-making capability among DC annuity holders (%)

| 55–64 | 65–74 | 75–84 | 85+ | All, 55+ | |||||

| Has difficulty managing money | 1.6 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 9.7 | 2.5 | ||||

| “Let’s say you have £200 in a savings account. The account earns 10% interest each year. How much would you have in the account at the end of 2 years?” | |||||||||

| £242 (correct answer) | 29.2 | 24.9 | 13.4 | 14.0 | 22.6 | ||||

| £240 (simple interest answer) | 41.8 | 37.3 | 40.9 | 31.8 | 38.9 | ||||

| Other answer | 29.0 | 37.8 | 45.7 | 54.2 | 38.5 | ||||

Source: English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, 2008–09 and 2012–13. Weighted using cross-sectional weights.

Table 2 presents some indicators of the ability of annuity holders to make a decision about whether or not to sell their annuity. The top row of the table shows what percentage of annuity holders report that they have difficulty managing their money because of a physical, mental, emotional or memory problem. The fraction that report difficulty with this is very small among younger annuity holders (less than 2% among those aged under 75) but rises to nearly 10% of annuity holders aged 85 and over.

The bottom part of the table provides an indication of higher-level financial capability – reporting answers to a question gauging individuals’ understanding of compound interest, which is a relevant concept in comparing the value of a lump sum and a future annuity income. The table shows that – even among annuity holders aged 55–64 – only 3 in 10 were correctly able to answer a question about compound interest. Among older annuity holders far fewer were able to give a correct answer: with only around 1 in 7 of those aged 75–84 or aged 85 and over giving the right answer.

This suggests that a significant minority of those who could potentially sell their annuity may not be able to work out accurately what a fair price for their annuity would be without proper advice or guidance.

There is also some evidence that individuals have difficulty valuing annuities compared to lump sums (albeit not from the UK and using experimental evidence rather than choices made in the real world). Brown et al (2013) presented individuals in the United States with an opportunity to buy a theoretical annuity and scenarios in which the same individuals were offered an opportunity to sell an annuity. Their experiments provide a number of pieces of evidence showing that individuals have difficulty valuing annuities and that the degree of difficulty with annuity choices is correlated with cognitive ability.

The researchers found a significant divergence between the prices at which individuals are willing to buy and sell annuities – with the price required to sell an annuity being typically significantly higher than the price at which people report being willing to buy an annuity. This divergence is greatest on average for those with the least cognitive ability (as measured by education, financial literacy, and numeracy).

Individuals’ valuations of annuities are also found to be sensitive to ‘anchoring’ effects. Specifically, they offered individuals various different prices at which to sell their annuity and they found that the price that individuals eventually agreed to sell at was affected by the price that they were first offered. That is, individuals who were initially offered a low price tended to end up agreeing to sell at a lower average price than individuals who were first offered a higher price. This ‘anchoring’ effect was much more likely among those with more limited cognitive abilities.

Summary

On the face of it, the Chancellor’s announcement in Budget 2015 that, from next year, people will be able to sell their annuities provides a welcome liberalisation of the market and is perhaps a natural next step to follow the changes made in Budget 2014. However, there is a significant risk that the secondary market for annuities will be limited or fail to emerge at all, due to the potentially significant problems of ‘adverse selection’ in this market. If this was the only issue, we might still not be unduly concerned about the changes. A more serious issue could arise from individuals’ potential inability to make well-informed decisions about whether or not to sell their annuity. Evidence suggests that at least a significant minority of annuity holders – in particular, older annuity holders – may struggle with the complex decisions required in valuing their annuity compared to an alternative lump sum. This suggests that, at the very least, individuals will need to have access to good quality financial advice and guidance in order to navigate this new market – if, indeed, such a market does spring into existence.