People on middle and higher incomes in the UK need to save for retirement. A full new state pension is worth just over £9,100 per year, which is unlikely to be enough to maintain working life standards of living into retirement for most people. Deciding when, and how much, to save for retirement is largely up to individuals. But this is difficult, and requires individuals to be forward looking, to think about their likely retirement needs as compared to their current spending, and to judge the risk and return to saving in different forms. One particular trade-off faced by many is how much to save in a private pension versus how much to save for, or spend on, owner occupied housing. These are the two most important forms of wealth, and the difficulty of choosing how much to save in these forms (and when) is compounded by the fact that they are both illiquid: once made, pension contributions cannot be accessed until around ten years before the state pension age, while housing wealth can only be accessed through re-mortgaging or downsizing.

Despite the importance of understanding how well individuals are preparing for retirement, relatively little is known about how they trade-off saving in a private pension versus in housing or how the timing of these interact. In new research published today, we therefore examined interactions between housing and pension saving at two distinct points in life. The overarching finding is that most people do not appear to be adjusting the timing of their pension saving around their saving for, or spending on, owner occupied housing.

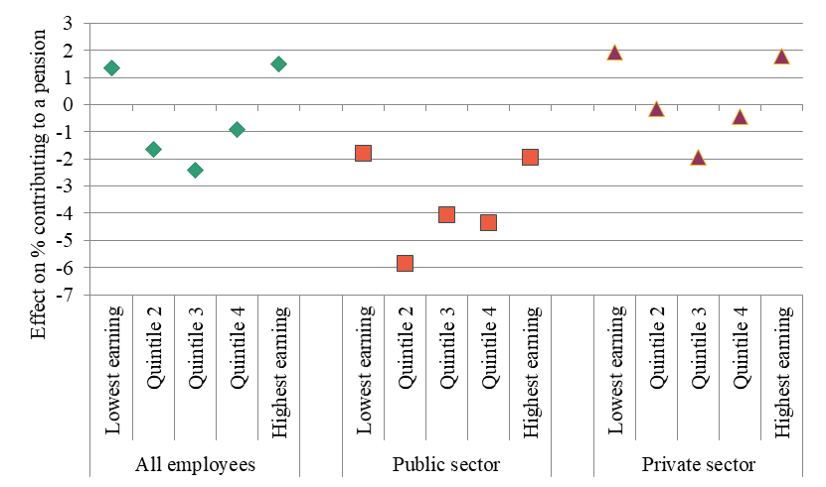

One paper examined the decision of young adults – before the introduction of automatic enrolment – as to whether to join a pension scheme, and whether that was influenced by local house prices. Given rapidly rising house prices over the last decade one might reasonably conjecture that individuals might have to save more for a deposit and that could lead them to postpone joining a pension. However, the research finds that pension membership decisions are relatively insensitive to local house prices. For young adults in the middle of the earnings distribution, an increase in local house prices of £150,000 (roughly the increase in average prices in England between 1997 and 2007) is estimated to lead to fewer than 3 in a 100 choosing not to save in a pension as a result. Those at the top and bottom of the earnings distribution are even less responsive, as is illustrated in Figure 1.

The effect is found to be greater for public sector employees than private sector employees, despite the more generous pension schemes available to those in the in public sector. The likely explanation is that the higher contributions required to these schemes (for example, 6% of earnings for teachers or those working in the NHS) are more difficult to make for middle-earning employees who are seeking to purchase more expensive property. But the effects are still small, with only a tiny minority of individuals reducing their pension membership in response to higher house prices.

Figure 1. Estimated effect on the pension membership rate of young employees from a £150,000 increase in real local house prices

Notes: Calculated by multiplying the results in Crawford and Simpson (2020) Table 4 and Figure 6 by 1.5.

The second paper examined pension saving at a later stage in life, specifically investigating whether older workers (those aged 54 to the state pension age) increase their pension saving when they finish paying off their mortgage. These individuals could increase their pension saving at this point without reducing their spending on other goods and services from recent levels. Average monthly mortgage repayments prior to repayment for those finishing their mortgage between 2004 and 2019 were over £400 per month per household, or over £200 per person. But only around 5% of individuals increased their pension saving at that point by more than £150 per month.

There are many important questions thrown up for future research: How do pension contributions change when people purchase their first home? Has automatic enrolment, and the increased pension saving as a result, slowed people getting on the housing ladder? What are people doing with the money they no longer spend on mortgage repayments? Is the behaviour of those who repay their mortgage ealier in working life different to those who repay later?

Not withstanding the answer to these questions, the research does suggest one practical implication for policy. Given persistent concerns that the minimum default pension contributions set by automatic enrolment are not enough, there may be merit in using the point at which a mortgage is repaid as a ‘nudge point’ or ‘teachable moment’ to increase pension saving. Behaviour does not currently change at this point for most, but people could increase their pension saving without a decline in their recent standards of living. Targeted communications, facilitated by mortgage lenders, HMRC and pensions providers, – perhaps asking individuals to precommit to increasing the pension contributions when their mortgage payments come to an end – could be one effective policy lever to encourage greater pension saving among those relatively well placed to do so.

Notes:

This research was funded by the IFS Retirement Savings Consortium, which comprises Age UK, Association of British Insurers, Aviva UK, Canada Life, Chartered Insurance Institute, Department for Work and Pensions, Investment Association, Legal and General Investment Management, and Money and Pensions Service, with co-funding from the ESRC-funded Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy.