On 25 November, the Chancellor will conclude the 2020 Spending Review. This will contain an update on the amount of funding provided to public services during this financial year (2020−21) as well as a new set of departmental budgets for the next (2021−22).

The decision to limit this year’s Spending Review to a single year, rather than the usual three or four, is a sensible one. The uncertainties at this moment in time are too great to publish a credible set of cash spending plans three or four years into the future: any such plans would be for the birds, as they would inevitably need to be revisited. That being said, a one-year settlement does have its downsides. Setting budgets for only one year can deprive public service leaders of the certainty they need to plan effectively and efficiently, and arguably adds to the fog of uncertainty already hanging over the wider economy. It is therefore welcome that the government has indicated that exceptions will be made where multi-year budgets are most needed – notably on funding for major investment projects.

While this Spending Review will be more short-term in its nature than usual, there are still a number of important things to look out for.

What to look out for:

1. The overall generosity of the Chancellor’s spending plans

In the March Budget – held just a few weeks before the UK entered lockdown and largely before any direct impact of COVID-19 on the UK economy had been factored into plans – Rishi Sunak announced that departments’ resource (day-to-day) budgets would grow by 4.4% above inflation between 2020−21 and 2021−22, to £361 billion in the latter year (in cash terms). Capital (investment) budgets were planned to grow by 12.5%, to £89 billion in 2021−22. A key question will be whether the Chancellor decides to be more or less generous than he was planning back in March – and by how much. This will be particularly important in determining the funding environment for ‘unprotected’ services not covered by pre-existing commitments.

2. What happens to previous commitments?

Decisions over large chunks of public service spending have already been made. NHS England already has a day-to-day funding settlement running up to 2023−24; plans for schools spending in England already extend up to 2022−23. These settlements ought to be viewed as a lower bound: schools are likely to receive extra funding to allow for ‘catch up’ learning, and the NHS budget will almost certainly be revised upwards. Whatever overall funding increase is announced by the Chancellor, a huge slice will go to the NHS and schools in England, with a corresponding amount allocated to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland via the Barnett formula.

The government is also committed to spending 0.7% of national income on official development assistance (ODA, or overseas aid) and at least 2% of national income on defence and national security. Because the economy is now expected to be smaller this year, a lower level of £ spending is required to meet targets expressed in terms of a percentage of national income. In the case of overseas aid spending, the government has indicated that it plans to cut £2.9 billion from the budget so as to avoid over-shooting the 0.7% target, but it is highly unlikely that a similar approach will be taken to defence spending. Next year, as the economy (hopefully) recovers, spending will also need to rise (unless, as is also possible, these targets are dropped entirely).

Together, these commitments mean that the path for something like two-thirds of public service spending has been (more or less) pre-determined. A major question for the Spending Review is what happens to the remaining third. Outside of Health, real-terms public service spending was cut by 20% (25% per person) over the decade to 2019−20. A sufficiently tight funding settlement could leave some of these ‘unprotected’ services – like the courts system, prisons, or local government – facing a further round of cuts.

3. How the Chancellor chooses to treat coronavirus-related spending

As of late July, departments had been allocated more than £70 billion for day-to-day public services in 2020−21 as part of the response to the pandemic, a figure that has continued to rise since. ‘Test and trace’ services alone have been allocated at least £12 billion. A crucial question is how much of this needs to continue into next year. One option for the Chancellor would be to allocate departments a budget for their ‘core’ or ‘business as usual’ services, and allow them to claim from a separate ‘COVID Reserve’ if needed. This would be similar in spirit to the previous use of a ‘Special Reserve’ to finance military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, rather than the core Ministry of Defence budget. But it might not be possible to draw such a clean distinction between ‘core’ spending and ‘COVID’ spending. If extra ‘catch up’ funding is needed to get through the backlog of court cases or NHS treatments, where would this fall? If it is now more expensive to provide standard social care or dentistry services because of the need for additional personal protective equipment, is that ‘core’ spending or an exceptional COVID-related pressure?

4. What happens to public sector pay?

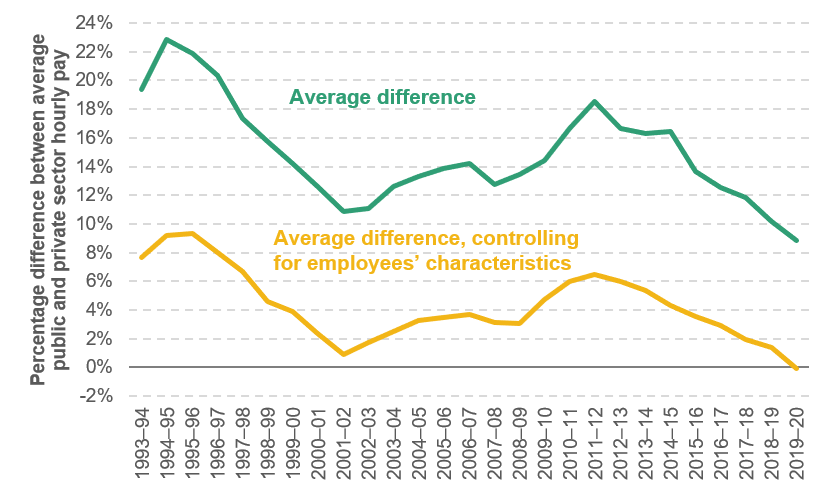

In 2019−20, the UK general government spent £204 billion employing around 5.4 million people. A major outstanding policy question for the Spending Review is what now happens to their pay. Over the decade prior to the pandemic, pay growth in the public sector was highly restrained: despite above-inflation pay awards in recent years, average earnings in the public sector in the first quarter of 2020 were 1.5% lower in real terms than 10 years previously. Relative to pay in the private sector, public sector pay had fallen to its lowest level in decades (Figure 1), likely exacerbating difficulties with recruitment and retention. This year, amidst the COVID-induced recession, public sector earnings are likely to perform more strongly than private sector earnings – just as was the case during and immediately after the Great Recession. Looking ahead, Rishi Sunak has stated that “in the interest of fairness we must exercise restraint in future public sector pay awards”. What this will mean in practice is unclear. The Chancellor’s language suggests that a return to the policy of the mid-2010s, where public sector pay increases were capped at 1%, is a real possibility.

5. Investment and infrastructure plans

The government has promised big on investment and infrastructure. The Spending Review is likely to see more of this, with pre-existing investment plans tied into the economic recovery, ‘building back better’ and the ‘levelling up’ agenda. One thing to look out for is whether new funding is announced, or future funding brought forward. Detailed allocations and credible delivery timetables would make it more likely that any such funding actually gets spent and – most importantly – spent well. Additionally, alongside the Spending Review, it is possible that the government will publish several related documents, including a National Infrastructure Strategy, a review of the Treasury’s investment rules (‘Green Book’), and a Research & Development place strategy. Together, these have the potential to influence and determine not just what the government invests in, but also where and how well.

6. Brexit-related spending decisions

The looming end of the transition period with the European Union will necessitate some Brexit-related spending decisions. Over the past five years, the government has spent around £8 billion on Brexit preparations. Some departments – notably the Home Office, HM Revenue and Customs, and the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs – are likely to require additional funding on a more permanent basis to reflect new post-Brexit responsibilities. HMRC, for instance, will almost certainly need to employ tens of thousands of new customs agents. The Chancellor will also need to take numerous decisions over replacements for existing EU spending done in the UK or on the UK’s behalf. This includes things like agricultural subsidies, research grants to UK universities, and regional support funds.

7. The broader outlook for tax, spending and the public finances

Alongside the Spending Review, on 25 November the Office for Budget Responsibility will publish a new set of forecasts for the economy and public finances. These will include the OBR’s latest estimates of the post-pandemic recovery in economic output and, consequently, in government revenues; the estimated cost of the government’s various policy responses; the outlook for the labour market; and the outlook for government borrowing and debt beyond this year, where government borrowing will be the highest the UK has seen outside of the two World Wars of the 20th Century. All of this is hugely important context for post-pandemic fiscal policy decisions. Additionally, the government could use the Spending Review as an opportunity to make announcements on things other than public services – perhaps most notably, a decision on whether or not to extend the £1,000 a year increase in the standard allowance for Universal Credit.

Beyond next year

The short-term nature of this year’s Spending Review is necessary, given the circumstances, and there are many important short-term decisions to be made. Looking to the future, the government should hold a ‘comprehensive’ multi-year Spending Review as soon as practicably possible, when some of the uncertainty over COVID-19, Brexit and the future of the economy has dissipated. At that point, when the worst of the pandemic is hopefully behind us, the Chancellor will need to grapple with the many long-term challenges facing the country. Questions around the future size and shape of the state, the role of technology in public service delivery, and how to achieve the government’s objective of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 are just some of those in dire need of ministerial attention and policy focus in the years ahead.

Figure 1. Difference between average public and private sector pay, 1993–94 to 2019–20

Note: Difference controlling for workers’ characteristics controls for differences in age, education, experience and region, all interacted with sex, following the same methodology as in Cribb, Emmerson and Sibieta (2014).

Source: Author’s calculations using Labour Force Survey.