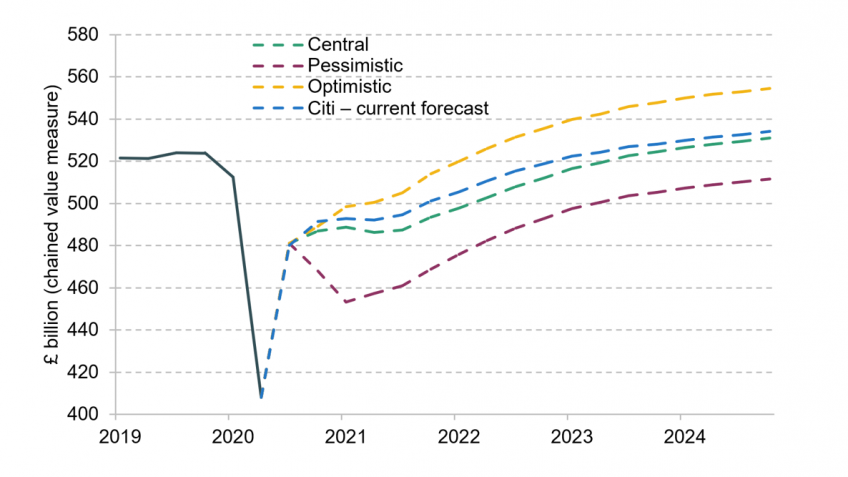

The UK faces a long road to economic recovery in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this chapter, we consider the near-term outlook in depth. Lockdown measures implemented in response to COVID-19 slashed nearly two decades of growth from the UK economy in March and April of this year. Since then, the economy has rebounded strongly on the back of the return of capacity and high levels of policy support.

However, we think this momentum is unlikely to last. Households have a key role to play in the recovery: firm balance sheets are weakened by the outbreak and the external picture remains complicated by Brexit and by other countries’ experiences of the pandemic. While backing the UK consumer has historically proven a sound bet, there are reasons why this time might be different. Lingering virus unease and broader uncertainty seem set to weigh on demand in the second half of 2020. With these effects concentrated in labour-intensive sectors, substantial increases in unemployment risk propagating the economic downturn – especially given the dialling down of policy support. We expect output in 2020 Q4 to remain more than 6% below 2019 Q4 levels – a larger drop than the peak-to-trough fall during the financial crisis. With permanent reconfiguration within the UK economy likely over the coming years, substantial policy support is likely to remain necessary for some time to come in order to avoid an even more prolonged crisis.

Scenarios for real quarterly UK GDP

Source: Figure 2.25 in Chapter 2.

Key Findings

1. Following a record 19.8% quarter-on-quarter (QQ) fall in the second quarter of 2020, we expect output to rebound by 17.5% QQ in Q3. Household consumption in particular has been recovering well, driven by the return of capacity, deferred expenditures and additional policy support.

2. But we expect the recovery to slow sharply from here. Virus fears, and weak associated demand, are instead likely to come to the fore. In our central scenario, 2020 Q4 GDP will remain 6.2% below 2019 Q4 levels, a larger fall than the 5.9% peak-to-trough fall during the financial crisis. Even by the end of 2024, we think GDP will still be only 1.9% above 2019 Q4 (and 4.7% below its 2016–19 trend).

3. The recovery from here hinges on households. Impaired business balance sheets and changes to trade patterns will likely weigh on investment and exports initially. By contrast, households on average saved a record 28.1% of their incomes during Q2 (compared with 6.1% between December 2016 and 2019). The question now is primarily about household confidence and whether it can drive a pick-up in spending. While possible, we are not optimistic.

4. The COVID-19 shock is unusually concentrated in labour-intensive sectors. Payroll data to August suggest there has already been a loss of over 700,000 employee jobs, even before the end of the furlough scheme. While official unemployment figures are confused at present, the fact that the Labour Force Survey suggests 500,000 more people than in March are out of work and want a job is a cause for concern. We expect the unemployment rate to increase to around

8–8.5% (2.8 million) in the first half of 2021, feeding back into weaker sentiment.

5. There are clearly enormous uncertainties surrounding all of these forecasts. Our outlook is conditioned on three judgements. First, we assume no effective protection against the virus is widely available before 2021 Q2; second, we expect lingering health concerns to weigh on demand until this point; and third, we anticipate that the medium-term reconfiguration (due to both COVID and Brexit) implies a larger and more persistent increase in unemployment, as well as an associated loss of capacity.