From tomorrow, for the first time in over a decade, the point at which people can claim a state pension (the “state pension age”) is simple. If you have reached your 66th birthday, you can claim it. Otherwise you cannot. For women, the state pension age (SPA) has risen from 60 in March 2010, reaching 65 two years ago in October 2018. From then on the state pension age rose for both men and women, to reach age 66 tomorrow.

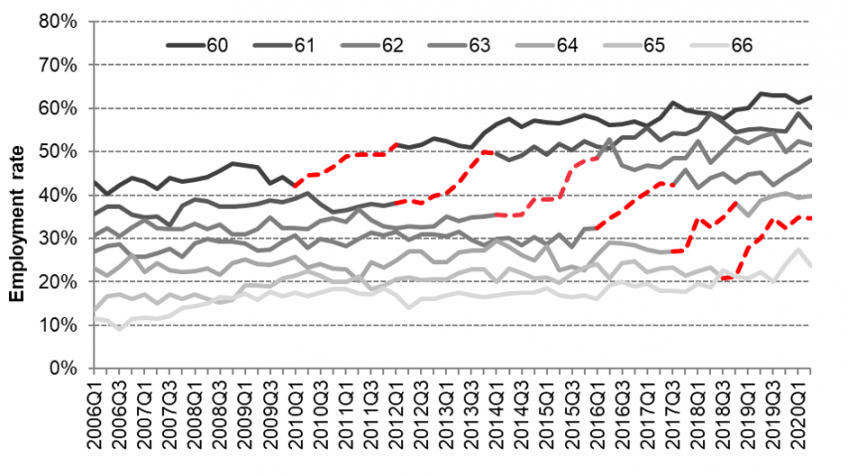

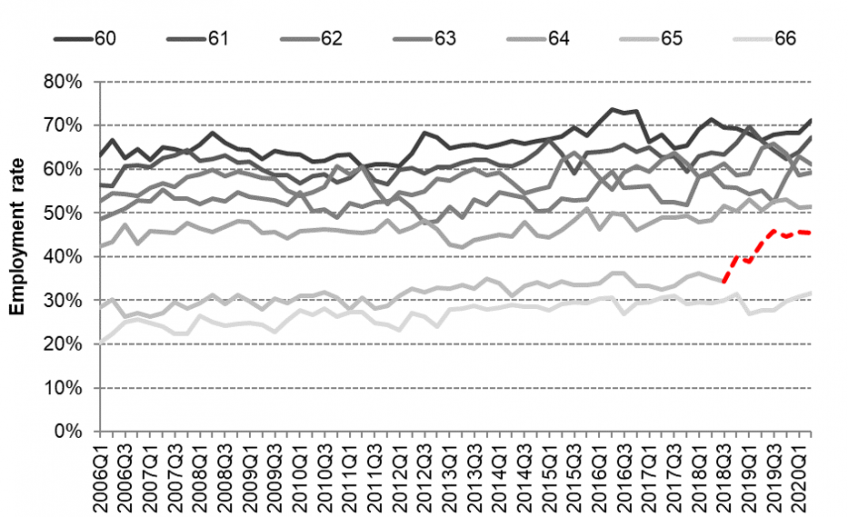

Previous research into the effect of the rise in the state pension age from 60 to 62 for women found that it led to an additional 6 out of every 100 women aged 60 or 61 being in paid work.[1] The Figure below shows that the further increases also look to have boosted the employment of older women. The Figure shows the percentage of women of different ages being in paid work since the mid 2000s, and the red dashed lines represent the periods in which state pension ages were rising for that group. Most notably, the employment rate of 65 year old women has shot up over the last 2 years as they were no longer able to claim a state pension. It rose from 21% in the third quarter of 2018 to reach 35% in the second quarter of 2020. 2020 Q2 was the height of the public health response to Covid-19 and therefore this employment rate will include many who were furloughed from their job. But even before the main effects of the pandemic hit, in 2020Q1, 65 year old women’s employment rate was also 35%.

Figure 1: Employment rate of women, by single year of age, 2006 to 2020

Notes: Headline employment includes people temporarily away from their jobs or who might be employed but are working zero hours in the interview week. Dashed lines indicate the period when the female SPA was rising for that age group. Source: Authors’ calculations using the Labour Force Survey.

Men, of course, have not seen the same increase in their state pension age in recent years, with the increases from 65 to 66 being the first ever increase in the SPA for men. Figure 2 is the equivalent to Figure 1, except for men instead of women. While the employment rates of older men have been increasing very gradually over the last decade, the recent increase for 65 year old men is striking as they were no longer able to claim the state pension. Their employment rate rose from 34% in the third quarter of 2018 to reach 45% in the latest data in 2020 Q2, again suggesting a substantial impact of the higher state pension age on the labour market activity of men. Combined with the gradual increases prior to the reform, the employment rate of 65 year old men has risen by around 15 ppts since 2010 from a baseline of around 30% (in other words, it has increased by half).

Figure 2: Employment rate of men, by single year of age, 2006 to 2020

Notes and Sources: See Figure 1.

Of course, the increased state pension ages for men and women do not only affect the likelihood of people retiring later. With the new state pension worth £175 per week, having to wait longer to claim a new state pension significantly reduces the incomes of most people affected by this reform. The counterpart to this is that a one-year increase in the state pension age for men and women reduces net government spending by around £3billion per year. With only a third of women, and just under half of men in paid work at age 65, this also means that many will have to finance the start of their retirement through their own savings or investments, or by relying on the – far less generous – working-age benefit system for support.

A new programme of work at the IFS – funded by the Centre for Ageing Better – will include a careful examination of the impact of the latest state pension age rise on employment and living standards of those at older working ages, in particular on the extent to which the impacts have varied across different groups.

After a decade of changes, the next few years are set to be a period of calm in the state pension age world. But come 2026, and change is afoot again, with the state pension age legislated to rise from 66 to 67 over the following two years, affecting all those born in April 1960 and later. Given the pattern of increases in employment seen over the last decade, this reform is likely to push up the employment rate of 66 year olds. Though note that over the last decade the employment rate of 66 year olds has already increased by almost a half for women, and by around a fifth for men.

************************************************

Notes:

This research was funded by the Centre for Ageing Better as part of a programme of work understanding Patterns of Work in Later Life.

This work was produced using statistical data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The use of the ONS statistical data in this work does not imply the endorsement of the ONS in relation to the interpretation or analysis of the statistical data. This work uses research data sets which may not exactly reproduce National Statistics aggregates. The Labour Force Survey data were supplied through the UK Data Archive. The data are Crown Copyright and reproduced with the permission of the controller of HMSO and Queen’s Printer for Scotland.

[1] See Cribb, Emmerson and Tetlow (2016). ‘Signals matter? Large retirement responses to limited financial incentives’, Labour Economics, 42, pp. 203-212