Today, the OBR published updated costings of the UK’s substantial package of fiscal measures in response to the coronavirus putting the amount of support at £123 billion. But despite the unprecedented size of the UK’s intervention, IMF estimates suggest that the response in other G7 economies has typically been larger. The bespoke coronavirus packages interact with the pre-existing benefit system in each country. Here, the UK stands out by offering a relatively low level of income support to employees without children who become unemployed. This is especially true compared with other European countries, whose insurance-based systems already provided a much greater level of insurance before any bespoke coronavirus schemes were implemented.

The coronavirus outbreak and associated containment measures have caused huge economic fallout across the world. The sharp decline in economic activity that is now occurring will depress government revenues and push up public spending. In addition, governments have, appropriately, responded with packages of fiscal measures that will help support households, businesses and public services through these challenging times and limit the long-run damage done by the crisis. But these measures will also have the direct impact of adding considerably more to government borrowing.

In the UK, government borrowing this year is likely to be the largest share of national income in peacetime, surpassing even that seen at the height of the global financial crisis in 2009–10 when borrowing reached 10.2% of national income (equivalent to around £200 billion in today’s terms, depending on how big the economy turns out to be this year).

According to initial estimates by the International Monetary Fund, the UK’s package amounts to £65 billion, or 3.1% of national income. In contrast, using the Office for Budget Responsibility’s Coronavirus policy monitoring database (as of 14 May 2020) gives an estimated cost of around £120 billion, or 5.9% of national income. In part, this difference reflects that the OBR’s costing was done more recently and therefore takes into account more recent announcements.

In addition, the discrepancy highlights the difficulty of costing the measures, and the uncertainty around the resulting estimates: the CJRS, through which the government pays up to 80% of the usual wages of furloughed employees for up to five months (with details of a new scheme that will run from the start of August through to the end of October still to come), is almost certainly going to be the costliest single direct measure, but its cost will depend on how many employees are furloughed and how much support they are eligible for, neither of which is easy to estimate.

An important contributor to the difference in costings is the outlook for the economy that they are based on. The OBR scenario projects that the UK economy will contract by 12.8% in 2020, whilst the IMF estimates a contraction of ‘only’ 6.5% – which would still be larger than the contraction during the financial crisis and the largest for a century. The IMF’s economic forecast would likely be associated with fewer employees being furloughed and therefore the direct cost of the CJRS being lower than under the OBR’s economic forecast.

Figure 1 shows the estimated size of other countries’ fiscal response so far, placing the UK firmly in the lower half of the G7 group of advanced economies. The OBR figure on the graph includes the CJRS through to the end of July 2020 (but not for the scheme that will be in place for the subsequent three months, as details of that are yet to be announced). Taking this higher costing, the UK package represents 5.9% of national income or £123 billion, comprising £118 billion of spending increases and £5 billion of tax cuts. While this is huge, it looks moderate in comparison with some other countries’ interventions.

Figure 1: IMF estimate of the size of the fiscal measures implemented in response to Covid-19

Note: Figure for Germany includes packages at both the state and federal level. OBR figure for the UK incorporates the extension of the CJRS until the end of July, but not for the scheme that will be in place over the subsequent three months as details of how that scheme will work are yet to be announced.

Source: International Monetary Fund, Fiscal Monitor – April 2020 (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2020/04/06/fiscal-monitor-april-2020) and Covid-19 Policy Tracker (https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19) with information up until 7 May; Office for Budget Responsibility Coronavirus Reference Scenario (https://obr.uk/coronavirus-reference-scenario/) and Coronavirus Policy Monitoring Database (https://obr.uk/download/coronavirus-policy-monitoring-database-14-may-2020/).

It is important to note though that the IMF estimates refer only to bespoke coronavirus packages. In fact, all modern economies have ‘automatic stabilisers’: progressive taxes and social insurance systems cushion the impact of any economic downturn, with the amount of tax owed lower and the amount of benefit entitlements higher when incomes take a hit. That is why the OBR, for example, suggests that borrowing will rise by close to £250 billion above what it previously forecast for this year, not ‘just’ by its £123 billion estimate of the cost of the coronavirus package. But the amount of insurance offered differs between countries.

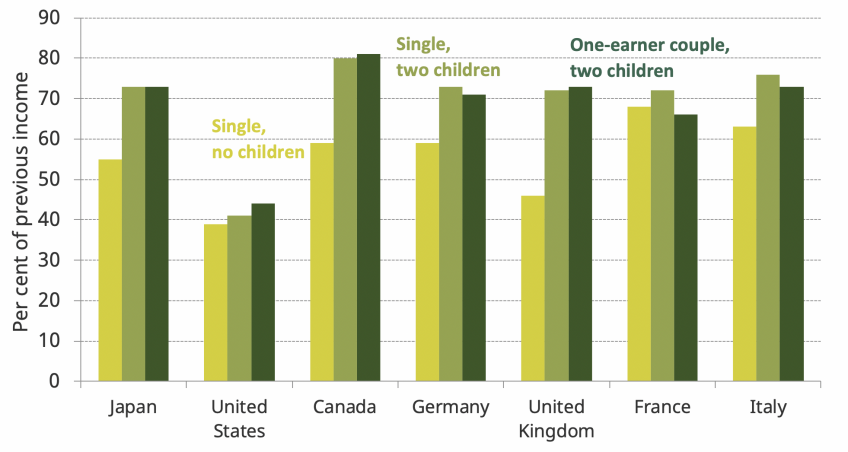

Part of that insurance comes through each country’s system of welfare benefits. Figure 2 plots an estimate (produced by the OECD) for the income that, prior to Covid-19 measures being implemented, an average earner would receive from the state were they to become unemployed, measured as a share of their current income. This is known as a replacement rate. In the US, a single childless person would have a replacement rate of about 40% and even a worker with two children would receive less than half their previous income in benefits. In contrast, a single and childless employee in a similar situation in France or Italy would be able to receive 60–70% of their previous income. Therefore, while the US has implemented a much bigger bespoke fiscal package in response to the pandemic than France or Italy, the relative generosity of the latter two’s existing social insurance system means that households were already much better insured against job loss before the pandemic and the fiscal response to it.

Figure 2: OECD estimate of the pre-Covid-19 unemployment insurance replacement rate

Note: Replacement rate shown for a person previously employed at the average wage, unemployed for four months in 2019 (2018 for Canada), including housing benefit. The other adult in the single-earner couple is assumed to be not in paid work, to have full work capacity but to have no entitlement to contributory benefits. Both adults are assumed to have met all behavioural requirements for benefit receipt and to have no other income.

Source: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development OECD.Stat, Social Protection and Well-Being: Net Replacement Rates in Unemployment.

In contrast, Japan has implemented a package amounting to a staggering 21% of national income, the largest one by some distance, but its replacement rate of 55% places it in the middle of the pack, rather than at the bottom, in terms of the generosity of its pre-Covid-19 unemployment insurance system. Canada’s relatively large package also comes on top of an insurance system which, at least for those with children, was generous when compared with other G7 countries.

The UK, in contrast, has introduced a comparatively moderate package: when taking the higher estimate for the UK, it is of a similar size to the packages implemented in Germany and France. All three countries’ packages include measures to protect workers’ incomes during the pandemic by increasing the generosity of their benefit system and putting in place measures to help prevent employees from being laid off. These measures interact with the benefit system that is already in place in each country in normal times. For parents who lose their job, the income support offered is broadly similar in all three countries (at least for an average earner and taking into account housing benefit). However, for those without children, the UK’s pre-Covid-19 tax and benefit system, with a replacement rate of just 46% including housing benefit, provides much less automatic support than the equivalent systems in Germany or France. Perhaps because of this, a key part of the UK’s bespoke coronavirus response – the £1,000 increase in the standard annual allowance in universal credit – will benefit childless claimants proportionally more, since they previously had a lower entitlement.

In this way, countries whose benefit systems already provided a broader group of workers with more generous levels of insurance in normal times may have found that they needed to spend less to top up this support in response to the coronavirus outbreak.

Isabel Stockton, a research economist at IFS and an author of the observation, said: ‘The UK government’s package of support for households, business and public services in response to the coronavirus is of a scale without precedent in the UK. But it is not large compared with the responses set out by governments of other G7 economies. It’s also important to remember that the pre-existing benefit system in the UK focuses on supporting families with children, offering less support to childless workers who become unemployed than the benefit system in, for example, Germany, France or Italy. This means that the UK would, if anything, need a larger bespoke package than those countries to guarantee a similar level of income support to all types of workers.’