Below we outline an initial response from IFS researchers on the Liberal Democrat manifesto. We take a number of policy areas by turn but this is not a full assessment.

Further analysis will be published over the next week.

Paul Johnson, IFS Director, said:

“The Liberal Democrats have followed Labour and the Conservatives in promising big increases in investment spending – a little bit more than the Conservative offer, still a lot less than the amount being proposed by Labour. Even so, their manifesto confirms that they are now the only major party committed to reduce the national debt as a fraction of national income, a goal now abandoned by both Labour and the Conservatives.

By far their most eye catching spending plan is a near quintupling in spending on universal free childcare – cementing an entirely new leg of the welfare state and offering a big boost to families with young children. We should though be cautious about expecting this to result in a big improvement in either child outcomes or a big increase in the number of parents in paid work. A £10 billion increase in the social security budget directed at working age families with more than two children, low earners and some disabled benefit recipients, also represents a substantial increase in spending. It would though still undo only a quarter of the discretionary cuts implemented since 2010.

Additional revenues would come from £37 billion worth of tax increases including increases in income tax and corporation tax rates, a reform to capital gains tax and a very big rise in air passenger duty. Nearly £6 billion is attributed to the dubious, if inevitable, “anti-avoidance” measures.

The biggest individual source of income for additional spending though would be the £14 billion 'remain bonus'. This is an estimate of the additional tax revenue (net of payments to the EU) accruing in 2024–25 as a result of the economy being, on their estimates, about 2% bigger than otherwise in the event of remaining in the EU. (The £50 billion bonus they focus on comes from cumulating additional revenues over five years.) Of course, there is a lot of uncertainty over such an estimate. That said if it were to become clear not only that we were going to remain but that that was a settled state for the long term, we could expect some additional growth and with it additional tax revenue. Their estimate is within the range of plausible estimates for the extent of that additional revenue.”

Taxes

Stuart Adam, a Senior Research Economist at the IFS, said:

“The Liberal Democrats say they would raise £37 billion a year through tax increases.

A little under half of this comes from straightforward increases in the rates of income tax and corporation tax. The rest comes from a range of measures with less certain revenue implications. Some would be more welcome than others, but most of them complicate the tax system.”

Most of that remaining revenue comes from three proposals to raise around £5 billion each:

- Abolishing the separate capital gains tax-free allowance is a sensible move in principle, but would extend the administrative burden of CGT to many more people and the revenue yield is highly uncertain.

- As parties unfortunately have a tendency to do, the Liberal Democrats promise to raise very large amounts – £5.7 billion a year – from ‘anti-avoidance measures’ without actually specifying which activities would be taxed more than they are now.

- Perhaps the most striking reform is to double revenue from air passenger duty while reducing it for those who take one or two international return flights per year. This implies a huge tax increase for more frequent flyers – and an entirely new administrative mechanism to monitor how many flights people have taken in a year.

The party also proposes major reforms to the tax system which are not intended to raise additional revenue:

- The proposed reform to business rates – replacing it with a land value tax levied on the property owner – would be welcome in principle, but again involves major practical challenges, to value the land separately from the buildings on it.

- A dedicated tax to fund health and social care sounds nice, but is misguided. There is no reason that spending on a particular item should be linked to revenue from a particular tax.

An extensive – and expensive – set of promises on the early years

- The Liberal Democrats are promising an enormous increase in spending on childcare – on their own costings, they plan an extra £13 billion of spending in 2024. That would leave spending on free childcare more than four-and-a-half times as high as it is set to be under current plans. This would represent a big increase in the scope of the welfare state covering the pre-school years.

- This represents a prioritisation of universal free childcare over, for example, programmes more targeted at the poorest. They are offering more hours, covering more weeks of the year, to more children, funded at a higher rate than currently. They would also target younger children (9 months to 2 years) in working families. This builds on the 2017 introduction of the 30-hour offer for 3- and 4-year-olds in working families.

- Additional free childcare hours would certainly help families with young children with their childcare costs. It is less clear that the new entitlement would be transformative for the outcomes of children or their families – existing research on free childcare in England finds relatively small effects on moving mothers into paid work, and concludes that benefits for children’s performance in school are also small and fade out quickly.

- The Liberal Democrats are also planning to match Labour’s commitment to spend an extra £1 billion on Sure Start children’s centres. This would reverse the two-thirds budget cut the programme has seen since 2010. The funding is likely to be most effective in improving children’s outcomes if targeted at more disadvantaged areas.

Christine Farquharson, a Research Economist at IFS, said: "The Liberal Democrats promises on childcare spending are much the most striking spending plans in their manifesto. They would dramatically expand the scope of the welfare state at younger ages. On their own costing they would increase spending on universal free childcare almost by a factor of five. This would of course come as a considerable benefit to many families by lowering their childcare costs, but evidence suggests it is unlikely to be transformative either on numbers of mothers in paid work or in terms of benefits to children's development."

Working-age benefits

- The Liberal Democrats’ manifesto implies increases in working-age benefit spending of the order of £10 billion per year, with rises targeted at low-income families in work and families with children.

- This money doesn’t go as far as it used to, because of underlying pressures pushing up benefits spending, including rising housing costs and a bigger population. Taking these into account, the Liberal Democrat’s pledges would reverse around a quarter of discretionary cuts to benefits since 2010.

Tom Waters, a Research Economist at IFS said, “The Liberal Democrat manifesto promised substantial increases in some working age benefits. They would end the two child limit in Universal Credit and tax credits, make adjustments to UC to increase incentives to work, and reverse some elements of recent cuts to housing and disability benefits. This would come at a cost of around £10 billion a year – a substantial amount, but still only enough to reverse around a quarter of the discretionary cuts implemented since 2010.”

Higher Education

- If maintenance grants were reinstated by reversing the 2016 reform that abolished them, this would mean that £2 billion worth of loans would be replaced with grants. However, the long run cost of this would be much lower – we estimate around £600 million for the 2020 cohort – because a large share of these loans would never be repaid anyway. Replacing loans by grants would leave the overall level of maintenance support for the poorest students unchanged and only affect later life repayments for relatively high earning graduates. There is little evidence that this would make more than a small difference to the participation of disadvantaged students.

- Stopping student loan sales to private investors seems sensible. As the government can currently borrow long-term at historically low interest rates, there is no reason to raise funds by selling assets. The sale makes even less sense when considering the fact that the collection burden remains with the government. Halting student loan sales is likely to save money for the taxpayer in the long run.

- The commitment not to make retrospective changes to the student loan repayment conditions is welcome. Students should know with a reasonable degree of certainty what the repayment terms on their loans will be, as any changes can substantially affect their finances.

- It is unclear what the benefits of another review of higher education finance would be. The recent Augar Review already provides a broad and up-to-date evidence base for policy.

- The new Skills Wallet policy could cost substantially more or less than the £1.6 billion the Liberal Democrats have budgeted for it, depending on the eligibility criteria for courses. Lax eligibility criteria could lead to very high costs and pose a risk of fraud. It is worth noting that Individual Learning Accounts, a similar (but much less generous) scheme introduced by the Labour government in 2000, had to be scrapped completely in 2001 as a result of widespread abuse of the system.

Jack Britton, a Senior Research Economist at IFS, said: "There is not much evidence to suggest replacing maintenance loans with maintenance grants would have much effect on participation in higher education. The £600 million cost might be more efficiently spent increasing total support for the poorest students rather than replacing loans with grants."

School spending

The Liberal Democrats have today announced a commitment to spend an extra £10.6 billion on schools in England in 2024–25 as compared with 2019–20. This would deliver a boost of £4.8 billion in real terms and a 11% increase on today by 2022–23. It compares with the £4.3 billion real-terms increase (10%) promised by the current government up to 2022–23. Both would effectively undo the 8% cuts to per pupil funding implemented since 2010, but would still mean more than a decade without spending growth up to 2022.

There are two significant differences with current government plans. First the Liberal Democrats would boost spending more quickly – by £4.6 billion next year against the government’s £2.6 billion. And they are promising an additional two years of increases through to 2024–25 taking the total cash (real terms) increase to £10.6 billion (£5.6 billion), delivering a total real-terms rise of 13% by 2024–25.

Their commitment to starting salaries of £30,000 for new teachers and salary rises for existing teachers largely match existing government plans.

Luke Sibieta, IFS Research Fellow, said “The Liberal Democrats have committed to a slightly larger increase in school funding over the next three years than existing government plans, but would get there much faster. This would provide an early boost, but wouldn't change the picture of a long-run squeeze on school resources, with no change in spending per pupil between 2009 and 2022”

Health spending

George Stoye, a Senior Research Economist at IFS said,

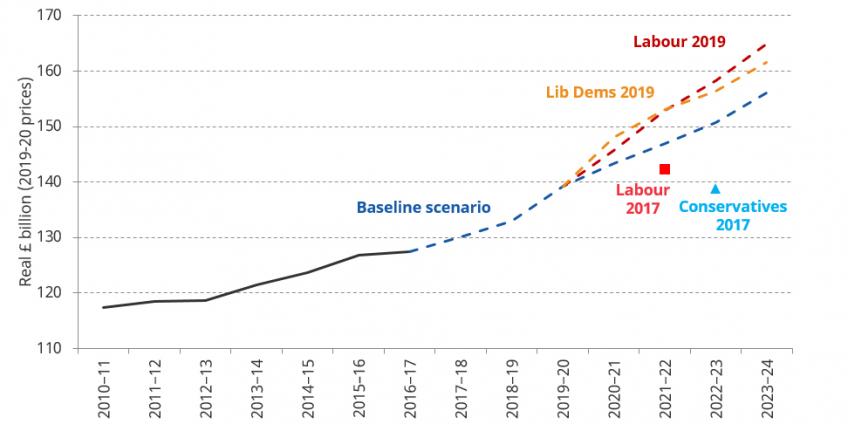

“All three main parties are proposing increases to health spending. Today’s proposals from the Lib Dems would increase day-to-day NHS spending in England by an average of 3.7% per year between 2019–20 and 2023–24, very similar to the 3.8% proposed by Labour and a bit above the 3.2% set out by current government plans for this period. These increases are broadly in line with most estimates of the funding increases required to meet pressures on the health service – and hence enough to keep things on an even keel, rather than enough to allow for dramatic improvements in quality.

Liberal Democrat plans also include increased funding for other day-to-day health spending in England and for capital investment. Taking this into account, spending on the Department of Health and Social Care would increase on average by 3.8% per year between now and 2023–24. This is a bit below the 4.3% increase implied by Labour’s plans set out last week, which included more generous capital funding plans in the later years. However Lib Dem plans are frontloaded and therefore higher for the first two years of the period.”

Liberal Democrat health spending plans would see real growth of 3.8% per year, versus 4.3% per year under Labour’s plans

Note: Figures denote Department of Health and Social Care total DEL, and include additional funding for pension costs. The baseline scenario assumes that non-NHS England resource DEL and DHSC capital DEL is frozen in real terms between 2020−21 and 2023−24. Labour 2017 and Conservative 2017 show the end-point of pledged spending using the 2017 manifestos and including equal additional funding for pension costs.

Investment spending

Ben Zaranko, a Research Economist at IFS, said:

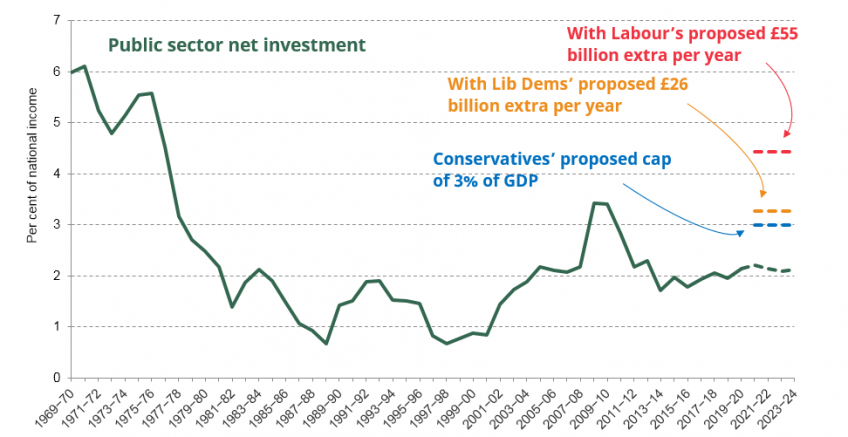

“The Liberal Democrats have followed Labour and the Conservatives in promising a substantial and ambitious increase in spending on public investment. Their plans to spend an additional £130 billion over the next five years would see public investment rise to above 3% of national income: more than what the Conservatives are planning, but less than Labour. All parties would face considerable challenges in delivering investment on this sort of scale - whether that be the challenge of finding worthwhile projects in which to invest, or the challenges posed by shortages of suitably skilled workers in the construction industry.”

All parties’ plans would mean a substantial increase in public investment over the next few years

Note: Forecasts of PSNI as a share of national income under Labour and Lib Dem plans take account of the impact on real output using multipliers from the Office for Budget Responsibility. Dashed green line indicates current forecasts. Calculations assume funding increases are smoothed so as to achieve PSNI constant as a share of national income over the course of the parliament.

Source: IFS calculations using OBR Public Finances Databank, OBR fiscal multipliers, and Spending Round 2019.