While the benefit system has undergone substantial reform over the past 10 years, there remain significant changes due to take place over the next parliament. The highest stakes relate to the continued roll-out of universal credit (UC), which integrates six existing benefits into one payment. Currently, about 2½ million families are on UC, but on existing plans that number will reach 7 million by 2024–25. While overall the reform does little to total benefit spending, millions of families see an increase in entitlement and millions see a loss – in both cases often in excess of £1,000 per year. Over the next parliament, the government will start to actively move claimants of existing benefits over to UC (rather than waiting for new claimants to apply). This poses significant risks: technical errors on the government’s part, or claimants not filling in the requisite forms, could result in families being left without support. The next government will also have to grapple with the continued controversy of the ‘five-week wait’ between when a claimant applies for UC and when they get their first payment. Whether and how to help bridge that gap is a key question for policymakers. The other major reforms that will continue to work their way in through the next parliament are the ‘two-child limit’ on support through means-tested benefits, and the abolition of the extra support that families get for their first child (known as the ‘family premium’). These are being very gradually rolled out, and will put pressure on the incomes of poorer families with children, especially larger families who are disproportionately in poverty.

Introduction

The last decade has seen huge changes to benefits. It is working-age benefits that have changed most dramatically, with a decade of substantial cuts alongside a truly radical overhaul to the structure of the whole system in the shape of universal credit (UC): through which a total of around £60 billion a year in support is eventually to be paid.

The vast majority of those cuts are now fully in place so one might think that, unless and until a new government announces a further set of reforms, the outlook for the benefit system is now relatively stable. For example, the 6.5% real cut to most working-age benefits since 2015 that has resulted from the four-year benefits freeze has now run its course, with benefit rates set to rise with prices once again from next April (as was always planned to be the case, despite the Conservatives ‘announcing’ it recently).

That would be to understate massively what lies ahead, however.

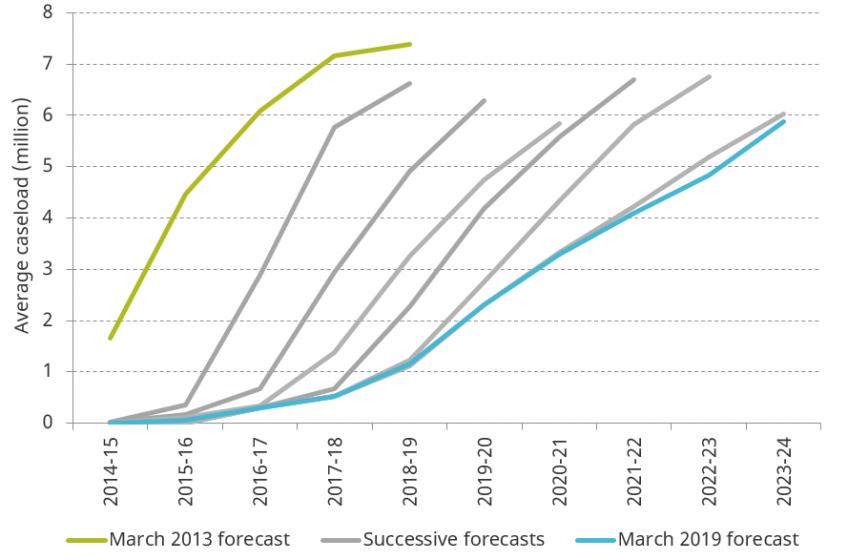

Despite the fact that universal credit seems to have been making bad headlines for years, there are still ‘only’ 2½ million families on it. These are all families who have begun a new benefits claim since UC became available to those with their circumstances in their area. In the end, about 7 million families – a quarter of all those of working age – are expected to be on it. The major remaining step is moving across to UC those who are still claiming one of the six benefits that it is replacing. This is being piloted in Harrogate, with the planned nationwide extension not, on the current timetable, due to be complete until the end of December 2023: though, as shown in Figure 1, UC’s roll-out has been delayed repeatedly since its inception.

Figure 1: Successive OBR forecasts for the roll-out of universal credit

Source: Authors’ calculations using Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook: March 2019, https://obr.uk/efo/economic-fiscal-outlook-march-2019/.

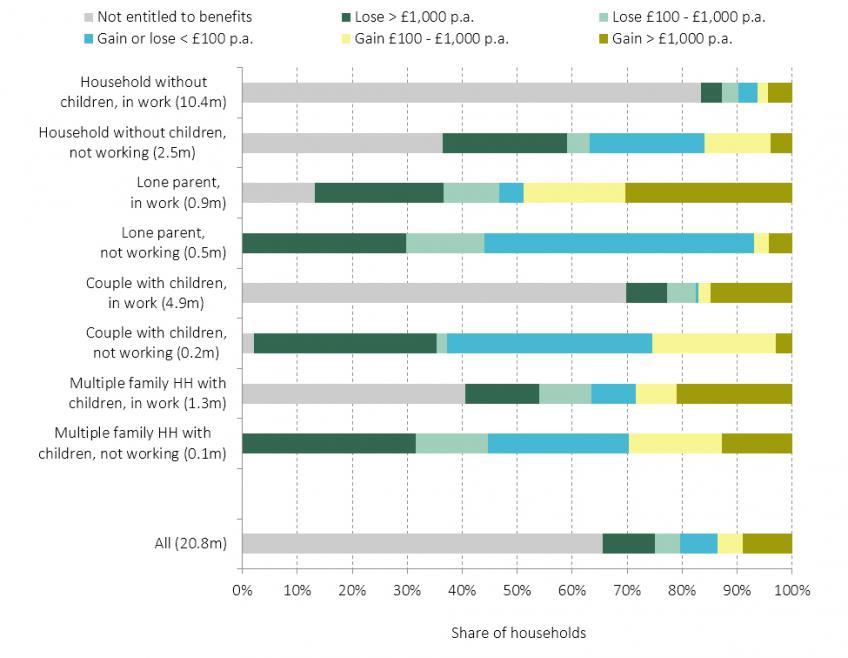

Universal credit – the challenges

A number of factors make the continued roll-out of UC challenging. First is simply the fact that UC changes the amounts of money that many people are entitled to (see Figure 2) – to be precise, about 80% of all working-age households entitled to means-tested benefits, and even more among households in work. It is important to appreciate that there will in fact be about as many winners as losers from this, that changing lots of people’s entitlements is inevitable with any reform that attempts to overhaul the structure of the system, and that if this is done without radically increasing total benefit spending it would inevitably create losers. It is also the case that any losses for those moved onto UC are supposed to be delayed by ‘transitional protection’ measures (more on these below).

When fully rolled out, about 2.8 million households will gain from UC in the sense that they will be entitled to at least £100 per year more in benefits than they would have got under the previous system, with 1.9 million gaining more than £1,000 per year. Groups particularly likely to win include one-earner families and working renters. Once transitional protections expire, about 3 million households will lose at least £100 per year, with 2 million losing more than £1,000 per year. Groups particularly likely to lose include those with significant unearned income or assets, working homeowners, certain disabled claimants and the low-income self-employed.

This final group is of particular importance. The low-income self-employed lose from UC because of the application of the ‘minimum income floor’, whereby self-employed claimants are treated as if they were working full time at the National Living Wage, even if they actually earn considerably less. This can generate large losses for self-employed claimants relative to the legacy system, but because new claimants to UC are given a one-year ‘grace period’ in which the minimum income floor does not apply, it is likely that few have been affected by it thus far. As those grace periods expire and more self-employed claimants are moved onto UC, this aspect of the system is likely to come under increasing political pressure.

Figure 2: Impact of universal credit reform on working-age households’ entitlements (number of households in parentheses)

Note and source: Authors’ calculations using Family Resources Survey, 2017–18, and TAXBEN, the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model. Working-age households are those containing an adult below pension credit age. Households are categorised as ‘not entitled to benefits’ if they would not be entitled to any legacy benefit or universal credit.

A second factor that makes UC’s continued roll-out challenging is that the process of moving existing claimants across to UC itself carries significant risks. Technical errors, such as failing to bring together data from multiple benefit systems, could result in some families being left without support. Moreover, rather than transferring people onto the new system automatically, the government’s current plan involves ceasing payments of legacy benefits and requiring individuals – some of whom will not have made a new benefit application for years – to make a new claim for UC within a specific time frame. This may be particularly difficult for some claimants with incapacities, who make up about half of the group who will be moved over to UC.[1] If they fail to do so in time, they will be left without benefits until they do start the new claim. Furthermore, for those whose circumstances are such that UC will be less generous than the system it replaces, having a gap between the claims could mean that they could lose out on the ‘transitional protection’ which ensures that they do not see any immediate loss of entitlement from moving to UC. Ensuring that affected families understand and are able to apply successfully as and when required is going to be crucial.

Third, there are features of UC besides levels of entitlement that have already caused difficulty and controversy. The scope for them to do so will only increase as more families come into contact with it. Many of these issues relate to the way in which payments are made – when, how often and who exactly they are paid to. The most infamous is the ‘five-week wait’ between when a claimant applies for UC and when they receive their first payment. A key question for the next government is whether and how to extend the loans (‘advances’) available to claimants that are intended to bridge this gap.

The stakes are very high. This is a system that affects millions of families at any one time, and many more at some point, and it tends to affect them during challenging periods of their lives. A universal credit that cannot be made to work well would be a disaster. The Labour party has already suggested that it would replace it with something else, although the specifics it has given amount only to tweaks to the system, and nothing remotely akin to scrapping it. This could well be a sensible approach. If the intention really were to replace UC with something fundamentally different – as opposed to, say, a rebranding exercise accompanied by small tweaks and/or a change to the amount spent on it – then this would effectively be a commitment to redesign the entire working-age means-tested benefit system for the second time in a decade. The administrative complexity and risks of once again moving millions of families onto a new benefit could be as great as the challenges that UC has already thrown up.

But it’s not just about universal credit

Universal credit is not the only reform that is still set to be working its way in over the next parliament (although it is quite commonly confused with these other reforms, which probably makes its perception even worse). The ‘two-child limit’ on support through means-tested benefits, and the abolition of the extra support that families get for their first child (known as the ‘family premium’), are the two main other policies effectively being rolled out gradually. This is because they apply to children born after April 2017. It will be the mid 2030s before all children are in that category. If the population then looks similar to now, the removal of the family premium would reduce benefits among 3.2 million households by an average of £550 per year (reducing benefit spending by £1.8 billion), while the two-child limit would be more narrowly focused, with 750,000 typically relatively low-income households losing an average of £3,600 per year (reducing benefit spending by £2.6 billion).

Over the next parliament, the number of families affected by these reforms will steadily increase, with the two-child limit affecting perhaps 500,000 families by 2025. This will put pressure on the incomes of poorer families with children, especially larger families who are disproportionately in poverty. The Labour party has already pledged to scrap the two-child limit.[2] While this would only immediately boost the incomes of the small number of households that are already affected by the policy (160,000 in April 2019[3]), it would protect a larger number of families that would otherwise be affected in the future if they were to have a third or subsequent child.

This briefing note has focused specifically on the benefits challenges that will materialise specifically in the next parliament. But there are also big longer-term pressures and difficulties with our benefits system that any government should be looking to address, including the role that the system has to play in supporting working families on low pay, people with high housing costs and those in ill health. These have been discussed in detail elsewhere: see https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14011 and https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/13936.

IFS analysis will examine the parties’ benefits proposals for thenext parliament comprehensively when manifestos are published. It is already clear that this will be not only a political battleground at the election but a critical area for the next government to get right.

[1] Chart 6.2 of Office for Budget Responsibility, Welfare Trends Report: January 2018, https://obr.uk/wtr/welfare-trends-report-january-2018/.

[2] https://labour.org.uk/press/corbyn-labour-will-scrap-universal-credit-immediately-lift-300000-children-poverty/.

[3] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/child-tax-credit-and-universal-credit-claimants-statistics-related-to-the-policy-to-provide-support-for-a-maximum-of-2-children-april-2019.