The fiscal targets bequeathed by former chancellor Philip Hammond all expire during the current forecast period. Moreover, the government has stated that it wants to keep open the possibility of a ‘no deal’ Brexit and, should this occur, it would require an important decision on how fiscal policy should adjust both in the near and long term. These two issues interact since any new fiscal targets ought to be carefully designed so that they are robust to plausible scenarios for the UK economy, not least around Brexit.

This chapter begins by considering the case for having fiscal targets at all and then discusses the government’s current fiscal targets and the rules proposed by the opposition Labour party. As well as critiquing these rules, we discuss how constraining they might prove to be under both current government policy and (in broad terms) under the policies that Labour set out in its 2017 general election manifesto.

Over the longer term, under a no-deal Brexit, the damage done to the economy would require some combination of tax rises and spending cuts. But in the near term, there could be a case for a temporary fiscal giveaway. The chapter outlines some of the key considerations when deciding upon the best fiscal policy response to an adverse economic shock and presents what a stylised fiscal stimulus in a no-deal scenario might do to growth, borrowing and debt.

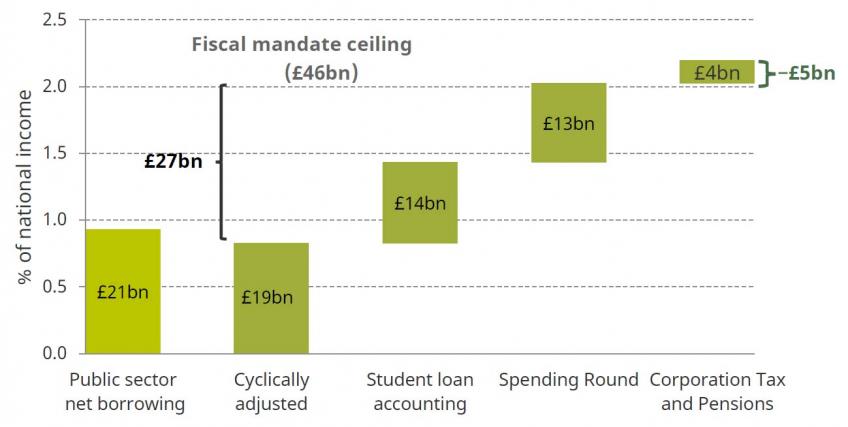

Changes to the outlook for cyclically adjusted borrowing in 2020–21

Key findings

- The current fiscal targets are no longer an anchor on fiscal policy. All expire during the current forecast horizon. In any case, (cyclically adjusted) borrowing appears on course to exceed the 2% of national income ceiling supposedly imposed by the fiscal mandate. If a ‘no deal’ Brexit happens, it would be difficult to imagine the supplementary debt target not also being broken.

- Labour’s 2017 proposal for a rolling forward-looking target of current budget balance has much to commend it. This would allow additional investment spending to be financed from borrowing when interest rates are low, and would also allow the chancellor some flexibility when responding to adverse shocks.

- But Labour’s 2017 proposal to have public sector net debt lower at the end of the parliament than at the start would be incompatible with its stated policies. A large programme of nationalisation and substantial boost to investment spending would increase the size of the public sector balance sheet, increasing both its liabilities and its assets. Regardless of the merits of these policies, public sector net debt would rise, not fall.

- Consideration could be given to targeting the projected path of public sector net debt over a longer horizon and also to the feasibility of setting a target that takes account of a broader set of public sector assets.

- If a ‘no deal’ Brexit occurred, fiscal policy would need to respond. Over the longer term, the damage done to the economy would require some combination of tax rises and spending cuts. But in the near term, there could be a case for a temporary fiscal giveaway. This could target parts of the economy where the short-run dislocations were particularly painful, or particularly likely to have adverse long-term effects. But the overall giveaway should be temporary.

- It is hard to imagine a set of short-term fiscal targets that would make sense both in the event of the UK leaving the EU with a deal and in the event of leaving without a deal. Any rules that constrained behaviour at all in the first case would be broken in the second. Given heightened uncertainty, rather than setting a target for borrowing or debt, the chancellor could consider instead setting a fiscal anchor to limit the amount of permanent tax cuts or further increases in day-to-day spending that is announced. This would not limit the chancellor’s options for borrowing to invest more or to deliver a temporary stimulus package. Well-designed fiscal rules could then be set out once at least some Brexit uncertainties have been resolved.