The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has a long history of conducting research on higher education, addressing the key questions of access, funding and returns. In this note, we summarise the recent evidence produced by the IFS which relates to the post-18 funding review, focusing particularly on the issues raised in Questions 5, 10, 13 and 16 of the call for evidence.

Returns

The first crucial issue underpinning the design of a higher education funding system is the impact of the education delivered on graduates and the economy as a whole. IFS researchers have been at the forefront of recent data developments providing new insights into the returns to higher education, being amongst the first researchers to access the linked HMRC-Student Loan Records (SLR) data and also the Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO) data.[1]

IFS research using the HMRC-SLR data supports the idea that there remains a substantial average earnings premium associated with going to university – at least when comparing people in their late 20s – but that there is also very wide variation in the earnings of graduates, including by institution and subject (Britton et al 2016). Indeed, it is clear from this research that individuals from some institutions studying some subjects earn less, on average, than individuals who have not gone to university.

This has fuelled debate about whether all degrees provide good value-for-money – for students, as well as the government. To comprehensively estimate value-for money for individuals and taxpayers, however, we need evidence on both the monetary and the non-monetary benefits of higher education (HE) and we need this not only for the individuals who access HE, but for society more widely. Public and non-monetary returns to education in particular are often difficult to measure, and the monetary returns to do not always provide a good guide to the overall benefits of particular degree courses. For example, there are degrees that offer considerable non-monetary benefits for society, such as nursing or social care, that may provide very low financial returns. Similarly, specialist arts degrees might provide low financial returns but high non-financial returns to the individuals that take them. It is difficult to abstract from the issues of public and non-monetary returns to HE when considering value-for-money of particular degree courses.

Level of funding

The second issue is the cost of providing this education, both to the government and to students. The latest IFS estimates suggest that the current system provides around £27,000 of teaching funding per student per degree in 2017 prices (Belfield et al. 2017a). This represents a higher level of funding per student per year than at earlier stages of education, but this differential has declined over the last thirty years. It is also worth noting that the trend in HE funding has been far from smooth. It is characterised by funding per student falling in real terms on a cohort-to-cohort basis, corrected by periodic fee reforms which substantially increase the level of funding per student, which is unlikely to be an optimal path.

Recent changes in HE funding have not impacted all subject areas equally. On average, the 2012 tuition fee reform increased funding per pupil by around 25%. However, the increase for the cheapest-to-teach subjects (in cost band D) was more than 45%, while the most expensive subjects (band A) only saw a 6% increase (Belfield et al 2017a). These – and any future changes in relative funding levels – are likely to have implications for how universities decided which courses to offer.

Who pays the cost?

The figure of £27,000 illustrates the level of upfront spending per student on undergraduate teaching; however, under the current system, over 95% of total upfront funding (including maintenance spending) is provided in the form of student loans, which graduates repay on an income contingent basis. So this raises the question of who is actually paying the cost of higher education?

The IFS has developed a robust graduate earnings model to estimate graduate earnings and loan repayments year-by-year over the 30 year repayment period, from which it is possible to calculate the overall long-run cost of higher education to graduates and government.[2]

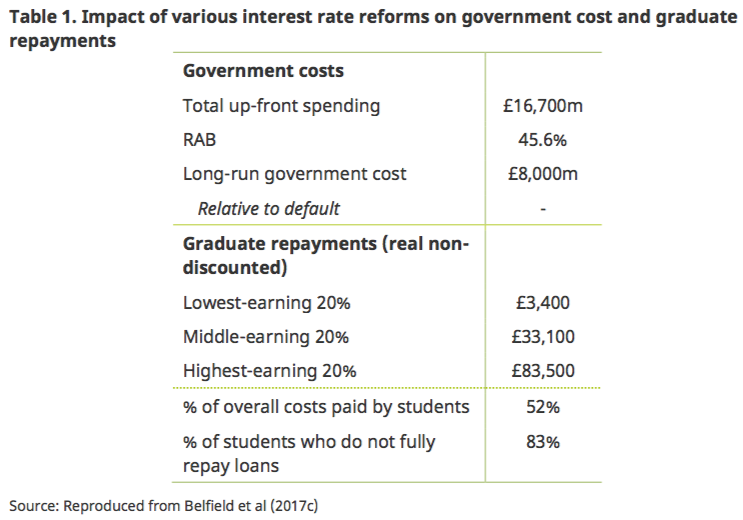

Table 1 summarises the latest IFS estimates of these costs. The government is estimated to initially pay out around £16.7 billion in teaching grants, tuition fee loans and maintenance loans to finance the degrees of students who entered HE in 2017. Graduates make repayments on these loans for up to 30 years after they graduate, however, meaning that the long-run cost to government is substantially lower. Our estimates suggest that around 45% of the value of loans paid out is not expected to be repaid (the RAB charge) and so the long run cost to government is this cost plus the grant spending, equal to approximately £8bn. This means that graduates pay the remaining £8.7bn (52%) and so the cost of providing HE under the current system is split roughly 50-50 between government and graduates.

Because student loan repayments are income contingent, not all graduates pay the same amount towards their education: while all students taking courses of similar length leave university with roughly the same amount of debt, high earning graduates repay more of their loans and low earning graduates repay less. We estimate that, under the current system, the highest earning 20% of graduates will pay more than £80,000 in loan repayments over their lifetimes (in 2017 prices), while the lowest earning 20% of graduates will only pay £3,400.Source: Reproduced from Belfield et al (2017c)

Given the differences in earnings between graduates studying different subjects at different institutions (as described in Britton et al., 2016), this implies that the government is likely to contribute more to the education of a fine arts graduate than to one studying medicine. However, mindful of our previous comments about the potential importance of the non-monetary benefits of different degrees, we note that the Review is an opportunity for public debate and greater transparency about the shape of higher education, the extent of the subsidy and the degrees to which it is currently being directed.

It is also important to consider how any potential reforms to the HE system are likely to impact graduate repayments. For the 83% of graduates who are not expected to fully repay their student loans, the loan system acts like a time-limited graduate tax, with repayments of 9% of their income above the repayment threshold made for the full 30 year repayment period. This means that changes that affect the total amount of debt that students accrue do not materially affect the repayments that most graduate go on to make. By contrast, changes which directly affect the repayments graduates are expected to make each year have a far greater impact on the amount they are likely to repay in total across the lifetime of the loan.

This was illustrated in 2017 when the government froze tuition fees in nominal terms at £9,250 and also increased the threshold above which graduates begin to make repayments on student loans to £25,000. Freezing fees (a net reduction relative to the previous policy) had little impact on expected graduate repayments, while increasing the threshold reduced the lifetime repayments of the average graduate by around £10,000 - costing the government more than £2bn per year in the long-run (Belfield et al., 2017b).

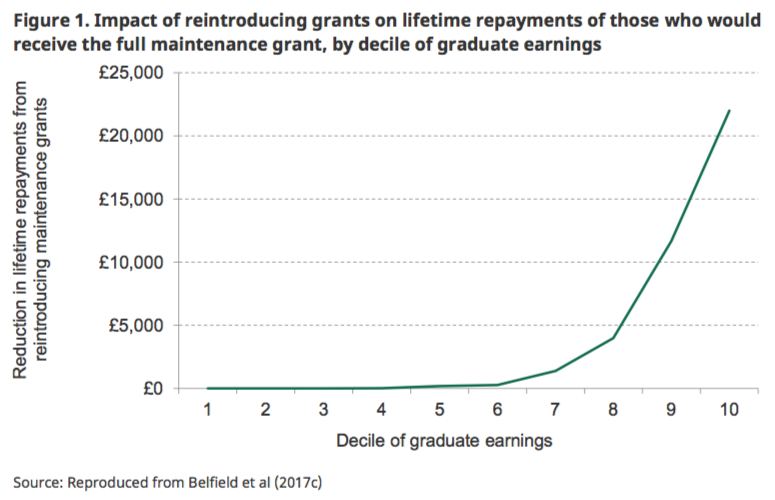

Similarly, this means that reforms like reintroducing maintenance grants (which lowers the debt levels of students from low-income families) or reducing the interest rate charged on graduate debt, are unlikely to reduce the amount of repayments being made by the vast majority of graduates. The only individuals whose repayments would be affected by such reforms are those middle-to-high earning graduates who repay or almost repay their student loans.

This is highlighted in Figure 1, which shows the impact on lifetime loan repayments of reintroducing maintenance grants for those who would be eligible for the full grant (assumed to be £3,500, fully replacing loans). It shows that only students from lower income families who go on to be in the top 40% of graduate earners are likely to benefit from the reintroduction of maintenance grants. Such a reform would be of little benefit to lower earning graduates in terms of reducing the overall cost of their education.

Incentives for universities and students

Under the current HE system in England, universities decide which courses to provide, how much to charge for them (subject to a fee cap) and how many students to take per course, and students decide which university to attend and what to study. As a result, the decisions universities and student make are vital to the efficient functioning of the system.

One way in which the government might influence the incentives of both students and universities is by creating price variation in the tuitions fees different universities charge for different subjects. One reason why the government might want to do this is to encourage more students to opt for subjects in which there are current or expected future skill shortages, e.g. STEM subjects. To change the incentives for students to take these courses without changing the incentives for universities to offer them, the government could consider reducing tuition fees and raising teaching grants for these courses. In Australia, for example, fees and teaching grants vary across courses. Subjects like law and economics have the highest fees and lowest teaching grants whereas shortage subjects like nursing have low fees and relatively high teaching grants.

We would note, however, that even without taking such an active approach, differential wages available to graduates who have studied different degree subjects should at least partially incentivise individuals to take higher paying subjects and hence subjects where skills are in short supply.

Moreover, the likely effectiveness and implications of reforming the system to incentivise students to take different subjects will depend on the reasons they are not already taking them. If it is because A-levels that are prerequisites to study STEM subjects at university are too difficult or otherwise unappealing, for example, then reducing fees to try to attract more students to take STEM subjects at university is likely to have little impact. Or if students are opting out of high return courses, this may be because the other courses deliver high individual non-pecuniary returns – in which case changing student behaviour would incur a cost in terms of these returns. However, if students face information problems and are simply not aware that STEM subjects are likely to be very well rewarded, then such a reform could have high returns (although of course here may be more direct ways to address this information failure).

Another motive might be to influence the decisions made by universities. One of the principles underpinning the introduction of the Teaching Excellence Framework was to see fees vary in line with some measure of ‘quality’ or value-added, therefore creating incentives for universities to increase quality. Value-added is notoriously difficult to measure – especially in HE, where universities award their own degrees. Assuming an appropriate measure could be agreed upon, recent IFS research has demonstrated that it would be possible to introduce incentives for universities to charge fees in line with their expected value-added (Belfield et al. forthcoming). Moreover, this could be achieved without necessarily increasing the overall cost of higher education to the government.

However, again the Review needs to be aware of the limitations of such an approach. First and foremost, using labour market earnings to judge quality is problematic because the earnings of those currently in the labour market relate to courses taken many years previously. Current earnings cannot be considered to be quality indicators for current provision. Further, as described above, there are non-monetary benefits from some degrees that are not captured in earnings. It would not be desirable for universities to be judged to be low quality because they provide a supply of graduates who can perform jobs that might have low financial returns but be socially valuable.

Conclusion

This note has briefly highlighted some of the areas in which IFS research may be able to contribute to the work of the panel. We would be very happy to elaborate on these issues or to provide further evidence to the panel in written or oral format if that would be useful.

References

Belfield, C. Crawford, C and Sibieta, L. (2016) – ‘Long-run comparisons of spending per pupil across different stages of education’, IFS Report R126

Belfield, C., Britton, J., van der Erve, L. and Dearden, L (2017a) – ‘Higher Education funding in England: past, present and options for the future’

Belfield, C., Britton, J. and van der Erve, L. (2017b) – ‘Higher Education finance reform: Raising the repayment threshold to £25,000 and freezing the fee cap at £9,250’, IFS Briefing Note BN217, https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/9964

Belfield, C., Britton, J. and Hodge,L. (2017c) – ‘Options for reducing the interest rate on student loans and reintroducing maintenance grants’, IFS Briefing Note BN221, https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/10154

Belfield, C., Britton, J. and Crawford, C. (forthcoming) – Skin in the game for universities? The potential implications of tying fees to graduate earnings

Britton, J., Dearden, L., Shephard, N. and Vignoles, A. (2016), ‘How English domiciled graduate earnings vary with gender, institution attended, subject and socio-economic background’, IFS Working Paper W16/06, https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/8233.

Crawford, C., Crawford, R. and Jin, W. (2014), Estimating the Public Cost of Student Loans, IFS Report R94, https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/7175.

Notes

[1] The Department for Education has recently funded our team to research graduate outcomes and how they vary by subject and institution using the LEO data.

[2] See Crawford, Crawford and Jin (2014) and Belfield et al. (2017a) for details on the model.