This chapter is part of the IFS Green Budget 2017.

Close to three-quarters of those aged 16–64 are in paid work. Driven in particular by strong growth in female employment over the last half a century, this is the highest overall employment rate seen in the UK since at least 1971. However, unsurprisingly, employment rates vary across different groups, not least between the non-disabled and the disabled. The Equality Act 2010 defines a disabled person as someone who has a physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on their ability to do normal daily activities.1 According to the Labour Force Survey (LFS), 17% of working-age individuals are disabled on this definition, with 81%of non-disabled working-age individuals in employment compared with just 49%% of disabled people. The government has highlighted, expressed concern, and committed to halve, this 32 percentage point disability employment gap. This goal is the focus of the recent publication Improving Lives: The Work, Health and Disability Green Paper produced jointly by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and the Department of Health (DH).

One aspect considered in the Green Paper, and the subject of this chapter, is the role of incapacity and disability benefits. Incapacity benefits – such as employment and support allowance (ESA) – are designed to provide financial support to those who cannot secure an income from employment due to disability or ill health. Disability benefits – such as personal independence payment (PIP) – are designed to compensate for increased costs of living incurred as a result of having a disability or poor health. Box 6.1 provides some more details of these benefits. The LFS suggests that of those working-age individuals who are out of work and disabled, just over half (53%) receive either incapacity benefits or disability benefits or both (16% receive incapacity benefits only, 18% receive disability benefits only and a further 19% receive both). This does mean that around 47% of those who are out of work and disabled (on this definition) receive neither benefit, so it is important to recognise that the benefits system is only a part of what the government should be thinking about.4 But it is a significant part and, as we shall see, it is an area of spending that has proven difficult to control and to predict, and a policy area that has been challenging in the sense that reforms have not always had the intended consequences.

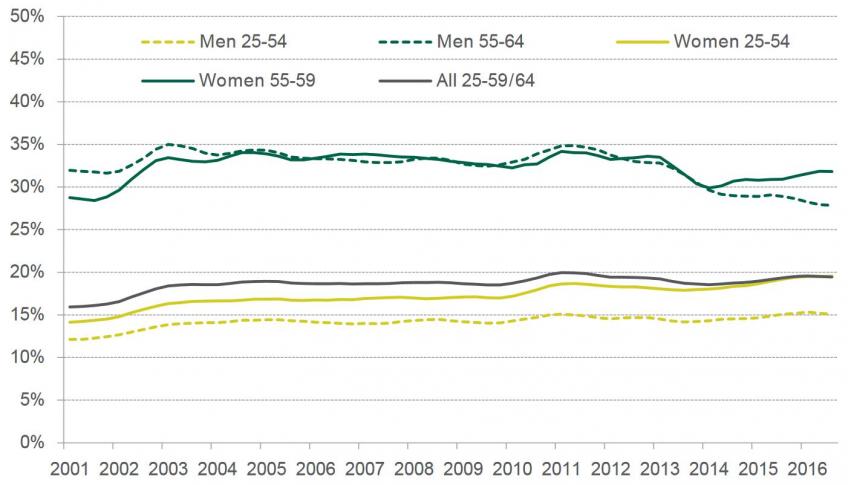

Figure. Rates of disability by age and sex (2001 to 2016)

Key findings

Incapacity and disability benefits make up a large share of total working-age welfare spending.

Just over half of disabled working-age people who are not in paid work receive disability or incapacity benefits. The government will spend £24 billion on these benefits for 3.5 million working-age people in 2016–17. This is 26% of non-pensioner benefit spending.

There has been a big shift from spending on incapacity benefits to spending on disability benefits over time.

Spending on incapacity benefits is now a smaller share of national income than in any year since 1989–90. In part, that reflects the fact that average awards have fallen from 24% of average earnings in 1986–87 to 19% in 2016–17. Meanwhile, spending on disability benefits for working-age people has consistently grown as a share of national income.

The government has committed to halve the ‘disability employment gap’.

17% of people of working age are disabled. 49% of them are in paid work, compared with 81% of the non-disabled. This suggests that the government ultimately wants around one-third of working-age disabled people who are not working to be in work.

The employment gap narrowed over the 2000s and has since been stable. Looking at those aged 25 and over, the gap is especially large among the low-educated: 42% versus 85%.

Incapacity benefit claims are increasingly concentrated among the low-educated, and less concentrated among older men, than in the past.

Low-educated men aged 25–34 are now twice as likely to receive incapacity benefits as high-educated men aged 55–64. This will present a significant challenge: closing the employment gap, and reducing the incapacity benefits caseload, will depend on increasing the labour market attachment of an increasingly low-skilled group.

There is considerable variation across Great Britain in the proportion of working-age individuals receiving incapacity benefits.

This proportion varies from 2.2% in the City of London to 13.0% in Blackpool. The proportion of working-age individuals in the ESA support group also varies dramatically.

Recent governments have struggled to achieve what they intended with reforms to incapacity and disability benefits.

In 2012, spending on incapacity benefits was forecast to be 27% lower in 2015–16 than in 2010–11; but instead it was 6% higher. So spending was £15 billion, not £10 billion as forecast. There is a need to avoid over-optimism about what further reform can achieve.

The government has proposed that Jobcentre work coaches have more discretion to engage the ESA support group in work-related activity in a way tailored to individual circumstances.

This is the group assessed as having limited capability for work-related activity, which has unexpectedly become the majority of incapacity benefits claimants. To deliver a substantial impact will certainly require considerably greater resources. The support group is 50% bigger than the group of ESA and JSA claimants (combined) who are already engaged in work-related activity.

Increased discretion could have positive consequences (e.g. engagement tailored to individual circumstances) or negative consequences (e.g. inconsistency in treatment of similar claimants).

The support group is a diverse group with a range of circumstances, and many of them have multiple health conditions. A particular challenge when potentially engaging them in more work-related activity will be treating those with mental and behavioural disorders appropriately. These disorders are now the primary health condition in half of ESA cases.