This week has seen various statements by public figures about borrowing and debt. George Osborne announced yesterday that the government will legislate to require the UK government to run a budget surplus ‘in normal times’. Meanwhile, the Scottish National Party have today tabled an amendment to the Scotland Bill to open up the possibility of full fiscal autonomy for Scotland, arguing that – even if this meant running a deficit in Scotland – this would be possible because ‘the UK has been in deficit in 43 of the last 50 years’.

So what level of borrowing can or should the UK or Scotland have in the longer-run? And what do the statements this week really mean?

Unfortunately, economic theory does not provide an answer to what the right level of borrowing for a country is. There are pros and cons of both higher and lower borrowing.

Most obviously, for a given level of taxation, lower borrowing requires lower spending. On the other hand, lower borrowing can lead to debt falling more quickly, leaving the country better placed to accommodate future pressures.

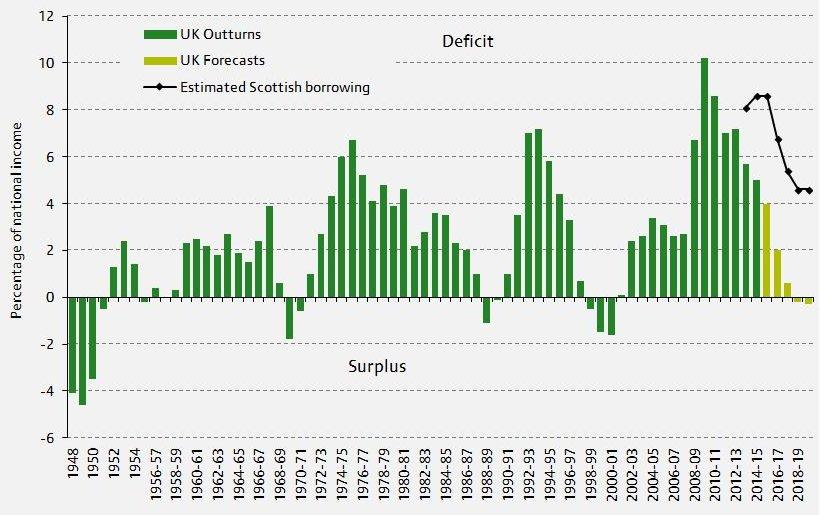

Figure 1. Borrowing

Notes: Figures for 1948–1954 are on a calendar year basis; figures for 1955–56 onwards are on a financial year basis.

Sources: Figures for the UK from Office for Budget Responsibility, Public Finances Databank, http://budgetresponsibility.org.uk/pubs/PSF_aggregates_databank_April_2015.V21.xls.

Projections for Scotland from D. Phillips, ‘Full fiscal autonomy delayed? The SNP’s plans for further devolution to Scotland’, April 2015, http://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/7722.

Figure 1 shows that the UK has actually run a budget surplus in only 12 years since 1948 (when comparable data begin) – and only one of the four surpluses since the mid-1970s was achieved without relying on an over-inflated economy.

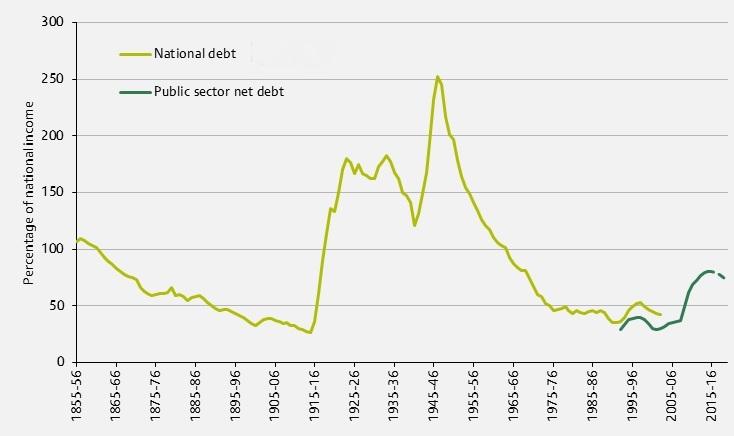

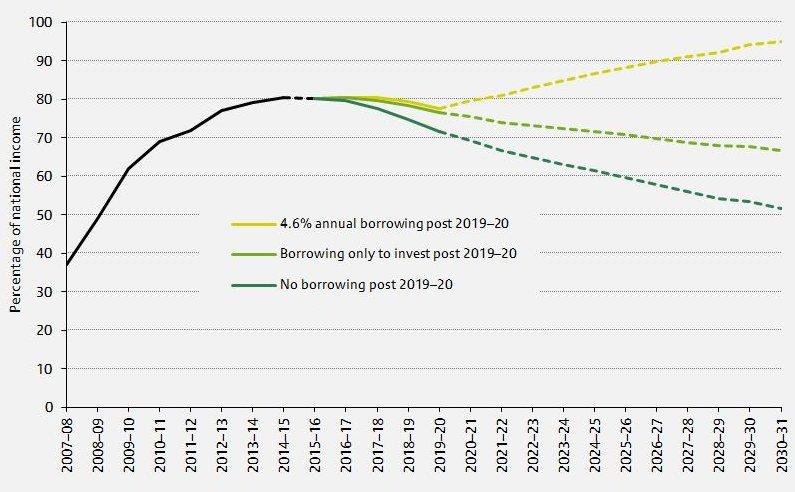

This suggests that budget surpluses are not a prerequisite for a successful economy. Indeed, running budget surpluses can come at an economic cost. The government does not need to balance its books every year in order to ensure that debt is sustainable – they could simply rely on economic growth (and inflation) to erode the value of outstanding debt over time, just as UK governments did for much of the post-war period (as shown in Figure 2). On the other hand, with a surplus, debt will fall more rapidly, getting the UK more quickly to a position where it could more comfortably absorb another large shock. Figure 3 shows some illustrative projections for debt. One projection assumes a balanced budget, another assumes that the government borrows to cover investment spending. Balancing the budget in the medium term would also leave the UK public finances better placed to accommodate the longer-term fiscal pressures of an ageing population, which the Office for Budget Responsibility highlighted today in their Fiscal Sustainability Report.

Figure 2. Debt

Source: Figures for National Debt are from the Debt Management Office. Figures for public sector net debt are from Office for Budget Responsibility, Public Finances Databank, http://budgetresponsibility.org.uk/pubs/PSF_aggregates_databank_April_2015.V21.xls.

There is, however, a limit to how much the government could borrow without debt starting to rise, rather than fall.

Turning to the specific case of the fiscal arithmetic for Scotland under full fiscal autonomy, our (now much-cited) calculations suggest that Scottish borrowing in 2015–16 would be 4.6% of national income higher than the equivalent figure for the UK as a whole. This is a result of the fact that spending per person in Scotland is higher than across the UK as a whole, while revenues per person are similar. The calculations use the same methodology as the Scottish Government use for allocating tax revenues and public spending between Scotland and the rest of the UK.

This would be the result under full fiscal autonomy if – as is usually assumed – such an arrangement entailed all taxes and the vast majority of spending being devolved to Scotland, with the Scottish Government making transfers to the UK government to cover a per capita share of things like defence, foreign affairs, and the UK’s existing debt interest payments.

This 4.6% of national income figure equates to £7.6 billion, and would put Scottish borrowing at 8.6% of national income this year (or a total of £14.2 billion), compared to 4.0% of national income for the UK as a whole. £7.6 billion is essentially a measure of the annual net fiscal transfer from the rest of the UK to Scotland this year.

Our estimates suggest that, if currently planned UK-wide spending cuts are applied in Scotland, Scottish borrowing would fall from 8.6% to 4.6% of national income by 2019–20, while the UK is forecast to move to a surplus of 0.3% of national income.

While the SNP are correct to say that the UK has run deficits in most of the last 50 years, Figure 1 shows that there have been very few years when the UK has run a deficit as large as 4.6% of national income. In fact, this has only happened during the recent crisis period, the recession of the early 1990s, and the troubled times of the mid- to late 1970s. Furthermore, were the UK to run borrowing at this level, debt would be likely to continue rising over the longer term, rather than falling (the third projection shown in Figure 3).

Figure 3. Public sector net debt profiles compared

Source: The “no borrowing” scenario and the “borrowing only to invest” scenario are from Figure 2.2 of Crawford, Emmerson, Keynes and Tetlow (2015), http://election2015.ifs.org.uk/article/post-election-austerity-parties-plans-compared. The “borrowing only to invest” scenario assumes public sector net borrowing of 1.4% of GDP from 2019–20 onwards. The “4.6% borrowing” scenario uses the same methodology.

What level of borrowing a government chooses in the longer-term is – to some extent – a political choice. Ahead of the recent general election there was a clear distinction between the Conservative party’s stated ambition to achieve an overall budget surplus – which Mr Osborne is now planning to set in law – and the proposals by Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the SNP to allow some borrowing.

Full fiscal autonomy would give the Scottish Government control over what and how to tax and what and how to spend. But, as mentioned above, it is generally assumed that it would also lead to them losing any net transfer from the rest of the UK. If this were the case, the higher deficit they would likely face would require them to find even bigger tax increases or spending cuts than those currently planned for the UK as a whole, to avoid their debt rising rapidly. In the longer-run, full fiscal autonomy might (or might not) lead to better policies that could generate higher economic growth in Scotland, and thus allow at least some of these additional tax rises or spending cuts to be reversed. But the consequences of the short run arithmetic are not easily avoided.